| FEIS Home Page |

|

||

|---|---|---|

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Meyer, Rachelle. 2012. Ranunculus glaberrimus. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/forb/rangla/all.html

[

].

Revisions:

01 August 2013: Distributional map from PLANTS Database added.

FEIS ABBREVIATION:

RANGLA

COMMON NAMES:

sagebrush buttercup

shiny-leaved buttercup

early buttercup

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of sagebrush buttercup is Ranunculus glaberrimus Hook. (Ranunculaceae). Recognized varieties are as follows [10,19,30]:

Ranunculus glaberrimus var. ellipticus (Greene) Green, elliptical buttercup

Ranunculus glaberrimus var. glaberrimus, typical variety

|

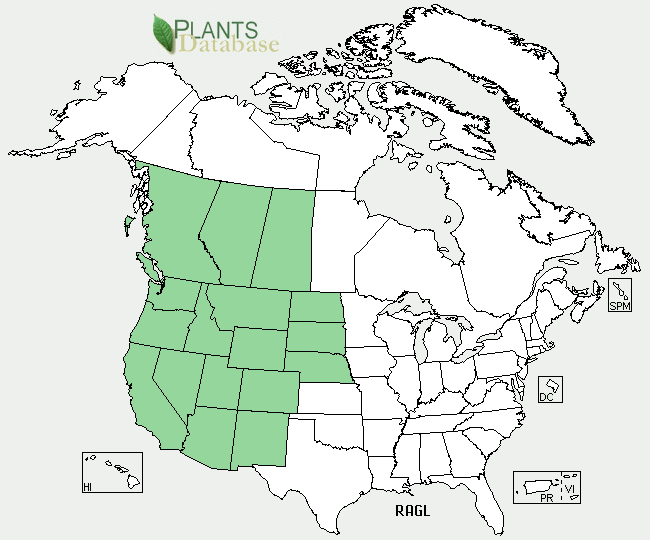

| Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2013. The PLANTS Database. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. (2013, August 1). |

Sagebrush buttercup is native to the United States and Canada. It occurs in portions of all the western United States east to Nebraska, the Dakotas [8,14,19,26,50], and from British Columbia [14,20] to southern Saskatchewan [42]. Elliptical buttercup is more widespread in the eastern areas of this distribution and may be the only variety that occurs in Colorado [23,48,49] and North Dakota [23,36]. Kartesz [23] considers the typical variety absent from Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Alberta. However, other floras do not describe such a restricted range for the typical variety. For instance, Munz and Keck [36] list the typical variety in New Mexico and Nebraska.

States and provinces [45]:

United States: AZ, CA, CO, ID, MT, ND, NE, NM, NV, OR, SD, UT, WA, WY

Canada: AB, BC, SK

Site characteristics: The 2 varieties seldom occur on the same site [19]. The typical variety grows on drier sites and at lower elevations [8]. In west-central Montana, the typical variety is most common in dry, open valleys and foothills [26]. Elliptical buttercup occurs in more montane areas [19,26].

| Table 1: Elevational ranges of the 2 sagebrush buttercup varieties by state. Dashes mean no information is available for that location and/or variety. | |||

| State | General elevation | Typical variety | Elliptical buttercup |

| California | about 5,000 feet (1,520 m) [36] |

900 to 3,300 feet (270-1,000 m) |

900 to 3,500 feet (270-1,070 m) [18] |

| Colorado | --- | --- | 5,000 to 10,000 feet (1,520-3,050 m) [9,17] |

| Montana | --- | 3,200 to 5,000 feet (980-1,520 m) |

3,200 to 9,000 feet (980-2,740 m) [9] |

| Nevada | --- | up to 5,500 feet (1,680 m) |

5,000 to 9,000 feet (1,520-2,740 m) [24] |

| New Mexico | --- | --- | 7,000 to 8,500 feet (2,130-2,590 m) [33] |

| Utah | 4,800 to 10,000 feet (1,460-3,050 m) [50] |

5,000 to 6,800 feet (1,520-2,100 m) |

5,500 to 9,000 feet (1,680-2,750 m) |

| Wyoming | --- | --- | 6,600 to 11,600 feet (2,010-3,540 m) [9] |

Sagebrush buttercup grows on sandy [4,24,36] or loamy soils [8].Growth on clay is described as fair to good, and growth on gravel as fair to poor. Optimum soil depth is 20 inches (51 cm) or more [9]. In southern Alberta, sites with sagebrush buttercup had well-drained soils [4].

In New Mexico sagebrush buttercup was described as occurring on wet ground [33], and in southeastern Washington and adjacent Idaho it might be abundant in moist places in the early spring [47]. In southern Alberta, sites with sagebrush buttercup were mesic [4].

Plant communities: Sagebrush buttercup is common throughout many plant communities including open woodlands [41], shrublands [5,34], grasslands [4,5,6,34], and subalpine [41] and alpine [42] meadows. It is most often associated with ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa)[7,11,14,19,50] and sagebrush communities [5,18,19,20,24,31,36,48,50], including those dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata subsp. wyomingensis) [53] and mountain big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata subsp. vaseyana) [13]. It is also present in woodland and forested communities comprised of fir and spruce (Abies-Picea spp.) [8], Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesia) [7,50], lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) [39,50], juniper (Juniperus spp.) [19], or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) [31,48,50].

The typical variety most commonly grows in lowland valleys in sagebrush and grassland communities or in parklands or open woodlands, while elliptical buttercup generally occurs in higher-elevation communities [18,19,24,36] such as upland sagebrush [19,24,36], mountain meadows [24,36], and montane coniferous forests [36]. These forests may be dominated by ponderosa pine [19,24], juniper [19], Jeffrey pine (P. jeffreyi), fir, and/or spruce [8].

See the Fire Regime Table for a list of plant communities in which sagebrush buttercup may occur and information on the fire regimes associated with those communities.Sagebrush buttercup is a perennial forb [4,18,26,50]. It typically grows 2 to 6 inches (5-15 cm) tall [19,44,46], but may grow to 10 inches (26 cm) tall [18]. The stems are erect to prostrate, 2 to 8 inches (5-20 cm) long [14,19], and do not root at the nodes [19,26,50]. Sagebrush buttercup has a cluster of fleshy [4,14,18,19,26], fibrous [4] roots 2 to 3 mm thick [14,19]. The mostly basal leaves are broad and rounded or ovate, with margins entire to lobed [14,19,20]. When present, the cauline leaves are generally dissected into 2 or 3 lobes [14,18,50]. The 5 sepals are commonly purplish-tinged [4,19,26]. The flowers occur singly, are 10 to 20 mm in diameter, and have 5 yellow petals [4]. Flowers in the Ranunculus genus are perfect [14,50]. Each sagebrush buttercup achene contains one seed [4]. From 30 to 180 achenes [4,14,19,50] occur in a semiglobose cluster at the top of the flower stalk. Achenes are slightly winged ventrally [14].

The main differences in appearance between the varieties are related to leaf shape [19,42]. Elliptical buttercup has entire, elliptic to oblanceolate basal leaves, while the typical variety has ovate to obovate, shallowly lobed basal leaves [14,17,19,26,33,48,50]. Variability between the 2 varieties makes distinguishing them difficult, especially in areas such as west-central Montana, where numerous transition forms occur [26].

Raunkiaer [38] life form:| SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT: |  |

|---|---|

| Lynne Robinson, www.rickandlynne.com |

Sagebrush buttercup is a cool-season species that flowers in early spring [44,46,47,48,49]. It is the first flower of spring throughout most of its range. Flowering generally begins in March [29] or April, but the length of flowering is variable [9]. It has flowered as early as January near Reno, Nevada [8], and in west-central Montana [26]. Growth is generally completed by midsummer [44].

Timing of flowering may be influenced by weather conditions including temperature and snow fall the previous winter. Sagebrush buttercup was 1 of 8 species that exhibited earlier (P<0.017) flowering over the course of a study that ran from 1995 to 2008 [29], a period of increasing average temperatures (IPCC 2007b cited in [29]). The amount of snowfall in the previous January and December was negatively associated (P=0.007) with average first-flowering date of the 8 species. March temperatures were also significantly (P=0.021) associated with mean first-flowering date of the 8 species, with first-flowering increasing by 1.5 days with every 1 °C increase in temperature [29]. In a big sagebrush/bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) community in southern British Columbia, growth of sagebrush buttercup and 4 other spring ephemerals was completed 1 month earlier in a year with a dry April compared to the previous year, in which April precipitation was above average [37].

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Immediate fire effect on plant:

Fire likely top-kills sagebrush buttercup. Because it flowers early in the year and disappears before midsummer [44], sagebrush buttercup is dormant when most fires occur in the plant communities it inhabits.

Postfire regeneration strategy [43]:

Caudex

or an herbaceous root crown, growing points in soil

Geophyte, growing points deep in soil

Possible:

Initial off-site colonizer (off site, initial community)

Secondary colonizer (on- or off-site seed sources)

Fire adaptations and plant response to fire:

Fire adaptations:

Little is known about the adaptations of sagebrush buttercup to fire. It is known to sprout in response to disturbance [9,53]. Wrobleski [53] categorized sagebrush buttercup as a species that can "endure" fire.

Plant response to fire: Relatively little is known about the manner in which sagebrush buttercup responds to fire, but it likely sprouts from the roots after fire. Postfire establishment from seed is also possible, although to date (2012), no information on sagebrush buttercup's ability to establish from seed was available (see Regeneration Processes).

In a western Montana study, sagebrush buttercup was present on first-year burn plots in grassland communities, while absent from adjacent unburned plots [35]. It was listed as occurring in vegetation that develops after fire or clearcutting in lodgepole pine in southern Wyoming [31]. In a Wyoming big sagebrush site in central Oregon, cover of perennial forbs, including sagebrush buttercup, recovered to prefire levels by the 2nd year after a fall prescribed fire. Differences in perennial forb cover between burned and unburned control plots were not significant. Crude protein levels of perennial forbs on this site were significantly higher on the burned site than on the control in the 2nd postfire year (P=0.011) but not in later years [40].

FUELS AND FIRE REGIMES:Fire regimes: Because sagebrush buttercup occurs in a variety of communities, it is subject to many different fire regimes ranging from surface fires every 8 to 10 years in some ponderosa pine woodlands to stand-replacement fires every few hundred years in certain lodgepole pine stands (see the Fire Regime Table). The fire seasons in these communities vary as well. Generally, the start of the fire season in the western United States occurs earlier than it did historically, primarily because of increased spring temperatures and earlier snow melts [3,51]. In 1970 the start of the first large wildfire (>1,000 acres (400 ha)) on Forest Service lands in the western states was in May. Since then, the first large fire has tended to occur earlier, with the first large wildfire in 2010 starting in March [3]. For information on fire regimes of communities were sagebrush buttercup occurs, see the Fire Regime Table and FEIS reviews of dominant species such as Pacific and interior ponderosa pines, Rocky Mountain lodgepole pine, Wyoming big sagebrush, and mountain big sagebrush. Find further fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes".

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:Palatability and nutritional value: The various parts of buttercups (Ranunculus) are eaten by many wildlife species including ducks, upland game birds, small mammals, and hoofed browsers [32]. Wildlife species generally use sagebrush buttercup early in the year because palatability decreases as it matures [44] and more preferred forage species are not yet available [8]. Sagebrush buttercup is a component of the sharp-tailed [12] and greater sage-grouse [15] diets. In southeastern Oregon and northwestern Nevada, sagebrush buttercup occurred in more than 15% of preincubating female greater sage-grouse crops from mid-March to mid-April, although it never comprised more than 3% of the aggregate percent dry mass. Sagebrush buttercup had high levels of calcium and phosphorus compared to low sagebrush (Artemisia arbuscula) [15]. In Montana, sagebrush buttercup comprised up to 3% of the volume of mule deer diets [21,52] and was present in 17% of mule deer rumens collected in spring [21]. Sagebrush buttercup was ranked as a low-quality elk food in spring and summer in the Gallatin River drainage of southern Montana [25] and excellent forage for pronghorn in Nevada (Einarsen 1948 cited in [16]). In contrast, ratings for elliptical buttercup for livestock and wildlife in the western United States were generally only poor to fair [9].

Domestic livestock eat sagebrush buttercup during the early spring, although plants are usually gone before these animals reach the range [44]. All species of Ranunculus have an "acrid taste" and, depending on the species, plant part, and season, may be toxic to cattle and horses. The toxic substances are volatile, however, and are dissipated during the drying process, which renders them nontoxic in hay [44].

Cover value: Due to its small stature, prostrate growth form, and patchy distribution, sagebrush buttercup provides little cover for wildlife.

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:| Fire regime information on vegetation communities in which sagebrush buttercup may occur. This information is taken from the LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment Vegetation Models [28], which were developed by local experts using available literature, local data, and/or expert opinion. This table summarizes fire regime characteristics for each plant community listed. The PDF file linked from each plant community name describes the model and synthesizes the knowledge available on vegetation composition, structure, and dynamics in that community. Cells are blank where information is not available in the Rapid Assessment Vegetation Model. | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Alpine and subalpine meadows and grasslands | Replacement | 68% | 350 | 200 | 500 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 32% | 750 | 500 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Bluebunch wheatgrass | Replacement | 47% | 18 | 5 | 20 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 53% | 16 | 5 | 20 | |||||||||

| Idaho fescue grasslands | Replacement | 76% | 40 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 24% | 125 | |||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Shrubland | |||||||||||||

| Low sagebrush | Replacement | 41% | 180 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 59% | 125 | |||||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush (cool sagebrush) | Replacement | 100% | 20 | 10 | 40 | ||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush semidesert | Replacement | 86% | 200 | 30 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 9% | >1,000 | 20 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 5% | >1,000 | 20 | ||||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush steppe | Replacement | 89% | 92 | 30 | 120 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 11% | 714 | 120 | ||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Woodland | |||||||||||||

| Oregon white oak | Replacement | 3% | 275 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 19% | 50 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 78% | 12.5 | |||||||||||

| Oregon white oak-ponderosa pine | Replacement | 16% | 125 | 100 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 2% | 900 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 81% | 25 | 5 | 30 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine | Replacement | 5% | 200 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 17% | 60 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 78% | 13 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine savannah (ultramafic) | Replacement | 7% | 200 | 100 | 300 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 93% | 15 | 10 | 20 | |||||||||

| Subalpine woodland | Replacement | 21% | 300 | 200 | 400 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 79% | 80 | 35 | 120 | |||||||||

| Western juniper (pumice) | Replacement | 33% | >1,000 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 67% | 500 | |||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Forested | |||||||||||||

| Douglas-fir (Willamette Valley foothills) | Replacement | 18% | 150 | 100 | 400 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 29% | 90 | 40 | 150 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 53% | 50 | 20 | 80 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir-western hemlock (dry mesic) | Replacement | 25% | 300 | 250 | 500 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 75% | 100 | 50 | 150 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir-western hemlock (wet mesic) | Replacement | 71% | 400 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 29% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Lodgepole pine (pumice soils) | Replacement | 78% | 125 | 65 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 22% | 450 | 45 | 85 | |||||||||

| Mixed conifer (eastside dry) | Replacement | 14% | 115 | 70 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 21% | 75 | 70 | 175 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 64% | 25 | 20 | 25 | |||||||||

| Mixed conifer (eastside mesic) | Replacement | 35% | 200 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 47% | 150 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 18% | 400 | |||||||||||

| Mixed conifer (southwestern Oregon) | Replacement | 4% | 400 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 29% | 50 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 67% | 22 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (xeric) | Replacement | 37% | 130 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 48% | 100 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 16% | 300 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine, dry (mesic) | Replacement | 5% | 125 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 13% | 50 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 82% | 8 | |||||||||||

| Spruce-fir | Replacement | 84% | 135 | 80 | 270 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 16% | 700 | 285 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Subalpine fir | Replacement | 81% | 185 | 150 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 19% | 800 | 500 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| California | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| California Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Alpine meadows and barrens | Replacement | 100% | 200 | 200 | 400 | ||||||||

| California grassland | Replacement | 100% | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||

| Wet mountain meadow-lodgepole pine (subalpine) | Replacement | 21% | 100 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 10% | 200 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 69% | 30 | |||||||||||

| California Woodland | |||||||||||||

| California oak woodlands | Replacement | 8% | 120 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 2% | 500 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 91% | 10 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine | Replacement | 5% | 200 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 17% | 60 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 78% | 13 | |||||||||||

| California Forested | |||||||||||||

| Aspen with conifer | Replacement | 24% | 155 | 50 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 15% | 240 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 61% | 60 | |||||||||||

| California mixed evergreen | Replacement | 10% | 140 | 65 | 700 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 58% | 25 | 10 | 33 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 32% | 45 | 7 | ||||||||||

| Jeffrey pine | Replacement | 9% | 250 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 17% | 130 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 74% | 30 | |||||||||||

| Interior white fir (northeastern California) | Replacement | 47% | 145 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 32% | 210 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 21% | 325 | |||||||||||

| Red fir-western white pine | Replacement | 16% | 250 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 65% | 60 | 25 | 80 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 19% | 200 | |||||||||||

| Red fir-white fir | Replacement | 13% | 200 | 125 | 500 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 36% | 70 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 51% | 50 | 15 | 50 | |||||||||

| Sierra Nevada lodgepole pine (cold wet upper montane) | Replacement | 23% | 150 | 37 | 764 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 70% | 50 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 7% | 500 | |||||||||||

| Sierra Nevada lodgepole pine (dry subalpine) | Replacement | 11% | 250 | 31 | 500 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 45% | 60 | 31 | 350 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 45% | 60 | 9 | 350 | |||||||||

| Southwest | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| Southwest Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Desert grassland | Replacement | 85% | 12 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 15% | 67 | |||||||||||

| Desert grassland with shrubs and trees | Replacement | 85% | 12 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 15% | 70 | |||||||||||

| Montane and subalpine grasslands | Replacement | 55% | 18 | 10 | 100 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 45% | 22 | |||||||||||

| Montane and subalpine grasslands with shrubs or trees | Replacement | 30% | 70 | 10 | 100 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 70% | 30 | |||||||||||

| Plains mesa grassland | Replacement | 81% | 20 | 3 | 30 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 19% | 85 | 3 | 150 | |||||||||

| Plains mesa grassland with shrubs or trees | Replacement | 76% | 20 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 24% | 65 | |||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie | Replacement | 87% | 12 | 2 | 35 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 13% | 80 | |||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie with shrubs | Replacement | 80% | 15 | 2 | 35 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 60 | |||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie with trees | Replacement | 80% | 15 | 2 | 35 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 60 | |||||||||||

| Southwest Shrubland | |||||||||||||

| Desert shrubland without grass | Replacement | 52% | 150 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 48% | 165 | |||||||||||

| Low sagebrush shrubland | Replacement | 100% | 125 | 60 | 150 | ||||||||

| Mountain-mahogany shrubland | Replacement | 73% | 75 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 27% | 200 | |||||||||||

| Mountain sagebrush (cool sagebrush) | Replacement | 75% | 100 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 25% | 300 | |||||||||||

| Southwestern shrub steppe | Replacement | 72% | 14 | 8 | 15 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 13% | 75 | 70 | 80 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 15% | 69 | 60 | 100 | |||||||||

| Southwestern shrub steppe with trees | Replacement | 52% | 17 | 10 | 25 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 22% | 40 | 25 | 50 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 25% | 35 | 25 | 100 | |||||||||

| Southwest Woodland | |||||||||||||

| Pinyon-juniper (mixed fire regime) | Replacement | 29% | 430 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 65% | 192 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 6% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Pinyon-juniper (rare replacement fire regime) | Replacement | 76% | 526 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 4% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine/grassland (Southwest) | Replacement | 3% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 97% | 10 | |||||||||||

| Riparian deciduous woodland | Replacement | 50% | 110 | 15 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 275 | 25 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 30% | 180 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Southwest Forested | |||||||||||||

| Aspen, stable without conifers | Replacement | 81% | 150 | 50 | 300 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 19% | 650 | 600 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Aspen with spruce-fir | Replacement | 38% | 75 | 40 | 90 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 38% | 75 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 23% | 125 | 30 | 250 | |||||||||

| Lodgepole pine (Central Rocky Mountains, infrequent fire) | Replacement | 82% | 300 | 250 | 500 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 18% | >1,000 | >1,000 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine-Douglas-fir (southern Rockies) | Replacement | 15% | 460 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 43% | 160 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 43% | 160 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine-Gambel oak (southern Rockies and Southwest) | Replacement | 8% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 92% | 25 | 10 | 30 | |||||||||

| Riparian forest with conifers | Replacement | 100% | 435 | 300 | 550 | ||||||||

| Southwest mixed conifer (cool, moist with aspen) | Replacement | 29% | 200 | 80 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 35% | 165 | 35 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 36% | 160 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Southwest mixed conifer (warm, dry with aspen) | Replacement | 7% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 13% | 150 | 80 | 200 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 80% | 25 | 2 | 70 | |||||||||

| Spruce-fir | Replacement | 96% | 210 | 150 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 4% | >1,000 | 35 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Great Basin | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| Great Basin Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Great Basin grassland | Replacement | 33% | 75 | 40 | 110 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 67% | 37 | 20 | 54 | |||||||||

| Mountain meadow (mesic to dry) | Replacement | 66% | 31 | 15 | 45 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 34% | 59 | 30 | 90 | |||||||||

| Great Basin Shrubland | |||||||||||||

| Basin big sagebrush | Replacement | 80% | 50 | 10 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 200 | 50 | 300 | |||||||||

| Black and low sagebrushes | Replacement | 33% | 243 | 100 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 67% | 119 | 75 | 140 | |||||||||

| Black and low sagebrushes with trees | Replacement | 37% | 227 | 150 | 290 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 63% | 136 | 50 | 190 | |||||||||

| Blackbrush | Replacement | 100% | 833 | 100 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Creosotebush shrublands with grasses | Replacement | 57% | 588 | 300 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 43% | 769 | 300 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Curlleaf mountain-mahogany | Replacement | 31% | 250 | 100 | 500 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 37% | 212 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 31% | 250 | 50 | ||||||||||

| Gambel oak | Replacement | 75% | 50 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 25% | 150 | |||||||||||

| Interior Arizona chaparral | Replacement | 88% | 46 | 25 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 12% | 350 | |||||||||||

| Montane chaparral | Replacement | 37% | 93 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 63% | 54 | |||||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush | Replacement | 100% | 48 | 15 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush (cool sagebrush) | Replacement | 75% | 100 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 25% | 300 | |||||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush with conifers | Replacement | 100% | 49 | 15 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mountain shrubland with trees | Replacement | 22% | 105 | 100 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 78% | 29 | 25 | 100 | |||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush semidesert | Replacement | 86% | 200 | 30 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 9% | >1,000 | 20 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 5% | >1,000 | 20 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush semidesert with trees | Replacement | 84% | 137 | 30 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 11% | >1,000 | 20 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 5% | >1,000 | 20 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush steppe | Replacement | 89% | 92 | 30 | 120 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 11% | 714 | 120 | ||||||||||

| Great Basin Woodland | |||||||||||||

| Juniper and pinyon-juniper steppe woodland | Replacement | 20% | 333 | 100 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 31% | 217 | 100 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 49% | 135 | 100 | ||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine | Replacement | 5% | 200 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 17% | 60 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 78% | 13 | |||||||||||

| Great Basin Forested | |||||||||||||

| Aspen with conifer (low to midelevations) | Replacement | 53% | 61 | 20 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 24% | 137 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 23% | 143 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Aspen with conifer (high elevations) | Replacement | 47% | 76 | 40 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 18% | 196 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 35% | 100 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Aspen-cottonwood, stable aspen without conifers | Replacement | 31% | 96 | 50 | 300 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 69% | 44 | 20 | 60 | |||||||||

| Aspen, stable without conifers | Replacement | 81% | 150 | 50 | 300 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 19% | 650 | 600 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Aspen with spruce-fir | Replacement | 38% | 75 | 40 | 90 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 38% | 75 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 23% | 125 | 30 | 250 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir (Great Basin, dry) | Replacement | 12% | 90 | 600 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 14% | 76 | 45 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 75% | 14 | 10 | 50 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir (interior, warm mesic) | Replacement | 28% | 170 | 80 | 400 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 72% | 65 | 50 | 250 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine-Douglas-fir | Replacement | 10% | 250 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 51% | 50 | 50 | 130 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 39% | 65 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine, interior | Replacement | 5% | 161 | 800 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 10% | 80 | 50 | 80 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 86% | 9 | 8 | 10 | |||||||||

| Spruce-fir-pine (subalpine) | Replacement | 98% | 217 | 75 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 2% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Mountain grassland | Replacement | 60% | 20 | 10 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 40% | 30 | |||||||||||

| Northern prairie grassland | Replacement | 55% | 22 | 2 | 40 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 45% | 27 | 10 | 50 | |||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Shrubland | |||||||||||||

| Basin big sagebrush | Replacement | 60% | 100 | 10 | 150 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 40% | 150 | |||||||||||

| Riparian (Wyoming) | Mixed | 100% | 100 | 25 | 500 | ||||||||

| Low sagebrush shrubland | Replacement | 100% | 125 | 60 | 150 | ||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush steppe and shrubland | Replacement | 100% | 70 | 30 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mountain shrub, nonsagebrush | Replacement | 80% | 100 | 20 | 150 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 400 | |||||||||||

| Wyoming big sagebrush | Replacement | 63% | 145 | 80 | 240 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 37% | 250 | |||||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Woodland | |||||||||||||

| Ancient juniper | Replacement | 100% | 750 | 200 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Forested | |||||||||||||

| Douglas-fir (cold) | Replacement | 31% | 145 | 75 | 250 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 69% | 65 | 35 | 150 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir (warm mesic interior) | Replacement | 28% | 170 | 80 | 400 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 72% | 65 | 50 | 250 | |||||||||

| Douglas-fir (xeric interior) | Replacement | 12% | 165 | 100 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 19% | 100 | 30 | 100 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 69% | 28 | 15 | 40 | |||||||||

| Grand fir-Douglas-fir-western larch mix | Replacement | 29% | 150 | 100 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 71% | 60 | 3 | 75 | |||||||||

| Grand fir-lodgepole pine-western larch-Douglas-fir | Replacement | 31% | 220 | 50 | 250 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 69% | 100 | 35 | 150 | |||||||||

| Lodgepole pine, lower subalpine | Replacement | 73% | 170 | 50 | 200 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 27% | 450 | 40 | 500 | |||||||||

| Lodgepole pine, persistent | Replacement | 89% | 450 | 300 | 600 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 11% | >1,000 | |||||||||||

| Lower subalpine (Wyoming and Central Rockies) | Replacement | 100% | 175 | 30 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed-conifer upland western redcedar-western hemlock | Replacement | 67% | 225 | 150 | 300 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 33% | 450 | 35 | 500 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Black Hills, low elevation) | Replacement | 7% | 300 | 200 | 400 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 21% | 100 | 50 | 400 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 71% | 30 | 5 | 50 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Black Hills, high elevation) | Replacement | 12% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 18% | 200 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 71% | 50 | |||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Northern and Central Rockies) | Replacement | 4% | 300 | 100 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 19% | 60 | 50 | 200 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 77% | 15 | 3 | 30 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Northern Great Plains) | Replacement | 5% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 75 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 75% | 20 | 10 | 40 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine-Douglas-fir | Replacement | 10% | 250 | >1,000 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 51% | 50 | 50 | 130 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 39% | 65 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Western larch-lodgepole pine-Douglas-fir | Replacement | 33% | 200 | 50 | 250 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 67% | 100 | 20 | 140 | |||||||||

| Whitebark pine-lodgepole pine (upper subalpine, Northern and Central Rockies) | Replacement | 38% | 360 | ||||||||||

| Mixed | 62% | 225 | |||||||||||

| Upper subalpine spruce-fir (Central Rockies) | Replacement | 100% | 300 | 100 | 600 | ||||||||

| Western redcedar | Replacement | 87% | 385 | 75 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 13% | >1,000 | 25 | ||||||||||

| Northern Great Plains | |||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | |||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

||||||||||

| Northern Plains Grassland | |||||||||||||

| Northern mixed-grass prairie | Replacement | 67% | 15 | 8 | 25 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 33% | 30 | 15 | 35 | |||||||||

| Northern tallgrass prairie | Replacement | 90% | 6.5 | 1 | 25 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 9% | 63 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 2% | 303 | |||||||||||

| Northern Plains Woodland | |||||||||||||

| Great Plains floodplain | Replacement | 100% | 500 | ||||||||||

| Northern Great Plains wooded draws and ravines | Replacement | 38% | 45 | 30 | 100 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 18% | 94 | |||||||||||

| Surface or low | 43% | 40 | 10 | ||||||||||

| Oak woodland | Replacement | 2% | 450 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 98% | 7.5 | |||||||||||

| *Fire Severities— Replacement: Any fire that causes greater than 75% top removal of a vegetation-fuel type, resulting in general replacement of existing vegetation; may or may not cause a lethal effect on the plants. Mixed: Any fire burning more than 5% of an area that does not qualify as a replacement, surface, or low-severity fire; includes mosaic and other fires that are intermediate in effects. Surface or low: Any fire that causes less than 25% upper layer replacement and/or removal in a vegetation-fuel class but burns 5% or more of the area [1,27]. |

|||||||||||||

1. Barrett, S.; Havlina, D.; Jones, J.; Hann, W.; Frame, C.; Hamilton, D.; Schon, K.; Demeo, T.; Hutter, L.; Menakis, J. 2010. Interagency Fire Regime Condition Class Guidebook. Version 3.0, [Online]. In: Interagency Fire Regime Condition Class (FRCC). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; U.S. Department of the Interior; The Nature Conservancy (Producers). Available: http://www.frcc.gov/. [85876]

2. Baskin, Carol C.; Baskin, Jerry M. 2001. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 666 p. [60775]

3. Climate Central. 2012. The age of western wildfires, [Online]. In: Climate Central. Princeton, NJ: Climate Central (Producer). 18 p. Available: http://www.climatecentral.org/news/report-the-age-of-western-wildfires-14873 [2012 October 16]. [86081]

4. Currah, R.; Smreciu, A.; Van Dyk, M. 1983. Prairie wildflowers: an illustrated manual of species suitable for cultivation and grassland restoration. Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta, Friends of the Devonian Botanic Garden. 290 p. [67345]

5. Daubenmire, R. 1970. Steppe vegetation of Washington. Technical Bulletin 62. Pullman, WA: Washington State University, College of Agriculture; Washington Agricultural Experiment Station. 131 p. [733]

6. Daubenmire, Rexford F. 1940. Plant succession due to overgrazing in the Agropyron bunchgrass prairie of southeastern Washington. Ecology. 21(1): 55-64. [735]

7. Daubenmire, Rexford F.; Daubenmire, Jean B. 1968. Forest vegetation of eastern Washington and northern Idaho. Technical Bulletin 60. Pullman, WA: Washington State University, College of Agriculture; Washington Agricultural Experiment Station. 104 p. [749]

8. Dayton, William A. 1960. Notes on western range forbs: Equisetaceae through Fumariaceae. Agric. Handb. 161. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 254 p. [767]

9. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The Plant Information Network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

10. Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2012. Flora of North America north of Mexico, [Online]. Flora of North America Association (Producer). Available: http://www.efloras.org/flora_page.aspx?flora_id=1. [36990]

11. Franklin, Jerry F.; Dyrness, C. T. 1973. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-8. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. 417 p. [961]

12. Giesen, Kenneth M.; Connelly, John W. 1993. Guidelines for management of Columbian sharp-tailed grouse habitat. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 21(3): 325-333. [23690]

13. Goodrich, Sherel; Huber, Allen. 2001. Mountain big sagebrush communities on the Bishop Conglomerate in the eastern Uinta Mountains. In: McArthur, E. Durant; Fairbanks, Daniel J., compilers. Shrubland ecosystem genetics and biodiversity: proceedings; 2000 June 13-15; Provo, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-21. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 336-343. [41998]

14. Great Plains Flora Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1392 p. [1603]

15. Gregg, Michael A.; Barnett, Jenny K.; Crawford, John A. 2008. Temporal variation in diet and nutrition of preincubating greater sage-grouse. Rangeland ecology and management. 61(5): 535-542. [86080]

16. Gullion, Gordon W. 1964. Wildlife uses of Nevada plants. Contributions toward a flora of Nevada: No. 49. CR-24-64. Beltsville, MD: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Crops Research Division; Washington, DC: U.S. National Arboretum, Herbarium. 170 p. [6729]

17. Harrington, H. D. 1964. Manual of the plants of Colorado. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: The Swallow Press. 666 p. [6851]

18. Hickman, James C., ed. 1993. The Jepson manual: Higher plants of California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 1400 p. [21992]

19. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur. 1964. Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 2: Salicaceae to Saxifragaceae. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 597 p. [1166]

20. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 730 p. [1168]

21. Kamps, George Frank. 1969. Whitetail and mule deer relationships in the Snowy Mountains of central Montana. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 59 p. Thesis. [43973]

22. Kartesz, J. T.; The Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2011. North American plant atlas, [Online]. Chapel Hill, NC: The Biota of North America Program (Producer). Available: http://www.bonap.org/MapSwitchboard.html. [Maps generated from Kartesz, J. T. 2010. Floristic synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP). [In press]. [84789]

23. Kartesz, John T. 1999. A synonymized checklist and atlas with biological attributes for the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. 1st ed. In: Kartesz, John T.; Meacham, Christopher A. Synthesis of the North American flora (Windows Version 1.0), [CD-ROM]. Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina Botanical Garden (Producer). In cooperation with: The Nature Conservancy; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service; U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. [36715]

24. Kartesz, John Thomas. 1988. A flora of Nevada. Reno, NV: University of Nevada. 1729 p. Dissertation. [In 2 volumes]. [42426]

25. Kufeld, Roland C. 1973. Foods eaten by the Rocky Mountain elk. Journal of Range Management. 26(2): 106-113. [1385]

26. Lackschewitz, Klaus. 1991. Vascular plants of west-central Montana--identification guidebook. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-227. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 648 p. [13798]

27. LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment. 2005. Reference condition modeling manual (Version 2.1), [Online]. In: LANDFIRE. Cooperative Agreement 04-CA-11132543-189. Boulder, CO: The Nature Conservancy; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; U.S. Department of the Interior (Producers). 72 p. Available: https://www.landfire.gov /downloadfile.php?file=RA_Modeling_Manual_v2_1.pdf [2007, May 24]. [66741]

28. LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment. 2007. Rapid assessment reference condition models, [Online]. In: LANDFIRE. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Lab; U.S. Geological Survey; The Nature Conservancy (Producers). Available: https://www.landfire.gov /models_EW.php [2008, April 18] [66533]

29. Lesica, P.; Kittelson, P. M. 2010. Precipitation and temperature are associated with advanced flowering phenology in a semi-arid grassland. Journal of Arid Environments. 74(9): 1013-1017. [81423]

30. Lichvar, Robert W.; Kartesz, John T. 2009. North American Digital Flora: National wetland plant list, version 2.4.0, [Online]. Hanover, NH: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory; Chapel Hill, NC: The Biota of North America Program (Producers). Available: https://rsgis.crrel.usace.army.mil/apex/f?p=703:2:497900423993445::NO::: [2012, April 4]. [84896]

31. Lukas, Laura E. 2012. A floristic inventory of vascular plants of the Medicine Bow Mountains, southeastern Wyoming. Laramie,WY: University of Wyoming. 56 p. Thesis. [85991]

32. Martin, Alexander C.; Zim, Herbert S.; Nelson, Arnold L. 1951. American wildlife and plants. New York: McGraw-Hill. 500 p. [4021]

33. Martin, William C.; Hutchins, Charles R. 1981. A flora of New Mexico. Volume 2. Germany: J. Cramer. 2589 p. [37176]

34. Massatti, Robert T. 2007. A floristic inventory of the east slope of the Wind River Mountain Range and vicinity, Wyoming. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming. 120 p. Thesis. [85993]

35. Mitchell, William W. 1957. An ecological study of the grasslands in the region of Missoula, Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana. 111 p. Thesis. [1665]

36. Munz, Philip A.; Keck, David D. 1973. A California flora and supplement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 1905 p. [6155]

37. Pitt, Michael D.; Wikeem, Brian M. 1990. Phenological patterns and adaptations in an Artemisia/Agropyron plant community. Journal of Range Management. 43(4): 350-358. [85990]

38. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

39. Reed, John F. 1952. The vegetation of the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park, Wyoming. The American Midland Naturalist. 48(3): 700-729. [1949]

40. Rhodes, Edward C.; Bates, Jonathan D.; Sharp, Robert N.; Davies, Kirk W. 2010. Fire effects on cover and dietary resources of sage-grouse habitat. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 74(4): 755-764. [82357]

41. Rundel, Philip W.; Gibson, Arthur C.; Sharifi, M. Rasoul. 2008. The alpine flora of the White Mountains, California. Madrono. 55(3): 202-215. [76003]

42. Scoggan, H. J. 1978. The flora of Canada. Part 3: Dicotyledoneae (Saururaceae to Violaceae). National Museum of Natural Sciences: Publications in Botany, No. 7(3). Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. 1115 p. [75493]

43. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species comprising secondary plant succession in northern Rocky Mountain forests. FEIS workshop: Postfire regeneration. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. 10 p. [20090]

44. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1937. Range plant handbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 532 p. [2387]

45. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2012. PLANTS Database, [Online]. Available: https://plants.usda.gov /. [34262]

46. Wambolt, Carl. 1981. Montana range plants: Common and scientific names. Bulletin 355. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University, Cooperative Extension Service. 27 p. [2450]

47. Weaver, J. E. 1917. A study of the vegetation of southeastern Washington and adjacent Idaho. Nebraska University Studies. 17(1): 1-133. [7153]

48. Weber, William A. 1987. Colorado flora: western slope. Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press. 530 p. [7706]

49. Weber, William A.; Wittmann, Ronald C. 1996. Colorado flora: eastern slope. 2nd ed. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. 524 p. [27572]

50. Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. The Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p. [2944]

51. Westerling, A. L.; Hidalgo, H. G.; Cayan, D. R.; Swetnam, T. W. 2006. Warming and earlier spring increase western U.S. forest wildfire activity. Science. 313(5789): 940-943. [65864]

52. Wilkins, Bruce T. 1957. Range use, food habits, and agricultural relationships of the mule deer, Bridger Mountains, Montana. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 21(2): 159-169. [1411]

53. Wrobleski, David W. 1999. Effects of prescribed fire on Wyoming big sagebrush communities: implications for ecological restoration of sage grouse habitat. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 76 p. Thesis. [30180]