| FEIS Home Page |

|

|

Photo by Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. 1995. Northeast wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. Northeast National Technical Center, Chester. |

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Zouhar, Kris. 2011. Muhlenbergia racemosa.

In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer).

Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov

/database/feis/plants/graminoid/muhrac/all.html [].

FEIS ABBREVIATION:

MUHRAC

NRCS PLANT CODE [82]:

MURA

COMMON NAMES:

marsh muhly

green muhly

creeping muhly

satin grass

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of marsh muhly is Muhlenbergia racemosa (Michx.) B.S.P.

(Poaceae) [5,9,12,24,43,44,55,71,86,90].

Some authors have indicated that marsh muhly is not readily separable from spiked muhly (M. glomerata) (e.g., [36,37,90]) and suggest that it is sufficient to lump them. Hitchcock and others [36,37] provide a key to separate them morphologically. Welsh and others [90] suggest that characteristic differences between these species are not consistent in specimens from Utah or the US National Herbarium. However, cytological [64,65], morphological (see Botanical description), and ecological (see Site Characteristics and Plant Communities) differences exist between these 2 species, so they are treated separately in the Fire Effects Information System. For information from the literature pertaining to spiked muhly, see the FEIS review. Because some authors cited in these reviews may have lumped or misidentified these 2 species, some information in this review may pertain to spiked muhly and vice versa.

According to Gleason and Cronquist [21], marsh muhly hybridizes with spiked muhly; however the literature on spiked muhly does not support this assertion (e.g., [64]). No other mention of hybridization in marsh muhly was found in the literature.

SYNONYMS:

Agrostis racemosa Michx. [43,44,90]

Muhlenbergia glomerata var. ramosa Vasey [9]

LIFE FORM:

Graminoid

|

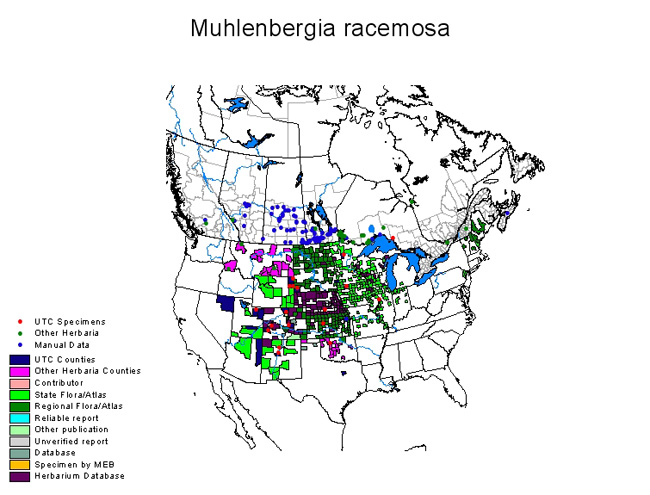

Map courtesy of Grass manual on the web, ©Utah State University (2 May 2011). |

Marsh muhly is most common in the north-central United States, but can be found at scattered locations throughout most of the western United States and into northern Mexico [5]. It is abundant in the prairie and plains regions and less commun in the mountain states at intermediate elevations [64]. Its occurrence east of Illinois also seems to be scattered and rare [72,82]; it is thought that marsh muhly spread to these locations from farther west [72,86]. One author suggests that marsh muhly was introduced along railways eastward from Kansas, Missouri, and Illinois [71], and another suggests that specimens from Maine and Washington, DC, "were doubtless from cultivated plants" [35]. Marsh muhly also seems to be rare or uncommon in the Pacific Northwest [37,52].

Marsh muhly occurs in the following countries, states, and provinces as of 2011 [82]:

Because some authors have lumped marsh muhly with spiked muhly (e.g., [36,37]), a distribution that reflects the combined distribution of both species is sometimes given (e.g., [37,90]). Hitchcock and others [36,37] suggest that marsh muhly is more common from the Rocky Mountains eastward, and spiked muhly is more common in the Pacific Northwest. Pohl [64] indicates that marsh muhly is adapted to much drier sites and regions than spiked muhly. According to Larson [50], spiked muhly is restricted to permanently wet habitats whereas marsh muhly occurs in a variety of upland and lowland habitats. Because some authors cited in this review may have lumped or misidentified these 2 species, some information in this review may pertain to spiked muhly.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

General site characteristics: Marsh muhly

occurs primarily in wetlands and riparian areas, from lowlands to subalpine meadows, but it also occurs in drier upland plant communities and disturbed areas. Marsh muhly frequents bogs and low grounds throughout its distribution [47] but occurs at elevations up to 11,000 feet (3,400 m) [5]. It occurs on a range of site types, from swamps, wet meadows, streambanks, and moist canyon bottoms [35] to rocky slopes, prairies, sandstone outcrops, and forest ecotones [5]. Throughout most of its range, marsh muhly is classified as a facultative wetland species: one that usually occurs in wetlands but is occasionally found in nonwetlands [82].

Marsh muhly seems to be a plant of generally low abundance but with high tolerances. It is frequently described in "waste places" [35,77] and disturbed areas associated with human settlement, including the margins of cultivated fields and along irrigation ditches, railways, and roadsides [5]. It is found in both moist and dry soils in all soil textures [77]. It occurs in both open plant communities (e.g., [71,83]) and in forest or woodland understories (e.g., [59,77,78]).

Site characteristics and plant communities by region: Marsh muhly seems to be most common in wetlands in the Great Lakes region, and in riparian areas in the Northern Great Plains and Southwest. It is also commonly described as occurring in disturbed areas throughout its range. marsh muhly is rarely a dominant species where it occurs, and typically has relatively low cover.

Canada: In Alberta marsh muhly occurred in a bog dominated by bog birch (Betula glandulosa) near the McLeod River. Marsh muhly was abundant in depressions in areas where ridges were dominated by shrub vegetation, and saturated or submerged depressions were carpeted with mosses and grasses. Marsh muhly also occurred in a tamarack (Larix laricina)-bog birch-Cosson’s limprichtia moss (Limprichtia cossonii) moor near Jolicoeur Lake and under tamarack in a calcareous muskeg [54].

Great Lakes: Marsh muhly occurs primarily in the western portion of the Great Lakes Region, where it is typically found in wet grasslands and peatlands near lakes, and less commonly in drier communities [10]. For example, wet prairies in Wisconsin may be dominated by bluejoint reedgrass (Calamagrostis canadensis), prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), and marsh muhly [10]. Marsh muhly was a characteristic species in western bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)-grasslands in northeastern Wisconsin [10,84,85]. In Dane County, Wisconsin, marsh muhly was a minor component in a reedgrass-sedge (Calamagrostis spp.-Carex spp.) association and in a hay meadow where tamarack had been removed by grubbing. It was more widespread, though still relatively infrequent, in a drained, reedgrass-sedge community succeeding to a big bluestem-dominated community [19]. Marsh muhly was "especially conspicuous" throughout a sedge mat community dominated by American woollyfruit sedge (Carex lasiocarpa var. americana) surrounding a lake at Itasca State Park, Minnesota, although it had relatively low abundance [57]. Marsh muhly was abundant in a bog in northern Illinois [18].

Some authors also note marsh muhly occurrence in disturbed sites and upland communities in the Great Lakes region such as moist, shaded roadsides and other disturbed areas at the Sand Ridge State Forest, Illinois [56]; dry soil along railroads in Michigan [86]; and dry prairies, rocks, and bluffs in Wisconsin [17]. Marsh muhly occurred in a native oak (Quercus spp.) savanna in eastern Minnesota [3] and was thought to be a component of the groundlayer vegetation in oak savanna in southern Wisconsin [4]. It occurred on limestone prairie in southern Wisconsin, and based on a review of pertinent literature and observations by ecologists in the area, marsh muhly was thought to prefer mesic, dry-mesic, and dry sites [4]. In Crex Meadows in Wisconsin, marsh muhly occurred in northern pine-hardwood communities, dominated primarily by jack pine (Pinus banksiana) and northern pin oak (Q. ellipsoidalis) [85]. It was present in both the aboveground vegetation and the seed bank of an old field in southwestern Ohio that was dominated by eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), American elm (Ulmus americana), and boxelder (Acer negundo) in the overstory, and by several introduced grasses, including Canada bluegrass (Poa compressa) and Kentucky bluegrass (P. pratensis), in the herb layer [53].

Northern Great Plains: Marsh muhly is most common in wet meadows, shores, and stream banks in the Northern Plains [50], such as moist meadows and low ground throughout Montana [8]; subirrigated meadows and stream margins in Wyoming [26]; riparian and wet grassland communities and moist microsites in prairies in Nebraska [62,75]; and floodplains along the Little Missouri River and its major tributaries in western North Dakota [29,87]. It is sometimes mentioned on dry sites (e.g., [12,13]) and disturbed areas (e.g., [24,50,75,76]), especially roadsides (e.g., [24,73]).

Marsh muhly is rarely a dominant or codominant species, with a few exceptions. It was among the dominant understory species on wet floodplains supporting relatively undisturbed, deciduous forests with closed canopies in Iowa [20]. It averaged 3.82% cover and codominated with sedges in at least one stand of wet tallgrass prairie in Iowa and eastern Nebraska. However, it had greater cover in mesic and wet-mesic communities with impeded drainage, where it had an average cover of 7.42% and 7.48%, respectively [91]. The greatest canopy cover reported for marsh muhly in the available literature, 40% (range 0-40%), was in disturbed and/or early to mid-seral stands of the boxelder/chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) habitat type in central and eastern Montana. This habitat type occupies woody draws that may occasionally be flooded by overland flows on terraces, fans, or floodplains along streams, rivers, lakes, springs, and ponds. Sites range in elevation from 2,100 to 4,000 feet (640-1,219 m) [30].

While marsh muhly is widespread in riparian communities in the Northern Plains, it typically has low abundance (<10% cover) and is rarely a community dominant. For example, marsh muhly was widespread in wooded draws studied in southern Saskatchewan, though typically with low canopy cover (<2%). Its highest average canopy cover in the area (7.4%) occurred in balm-of-Gilead (Populus × jackii) communities where wooded draws narrowed. It averaged 2.8% canopy cover in the Bebb willow (Salix bebbiana) community, which was restricted to narrow, gravel stream channels in bottoms where draws widened. It averaged 1.4% canopy cover in the silver buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea) community and ≤1% canopy cover in boxelder and chokecherry communities [51].

Marsh muhly occurs in several riparian plant communities dominated by eastern cottonwood, green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). In Montana, marsh muhly was more common in eastern cottonwood community types that represent grazing or browsing disclimaxes, and less common in eastern cottonwood communities that occurred on recent alluvial deposits and were relatively undisturbed by livestock or wildlife [30]. Marsh muhly was an important species (100% constancy and 8.3% average cover) in the understory of the green ash/western snowberry (Symphoricarpos occidentalis) habitat type in Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota. It occurred occasionally in the green ash/chokecherry habitat type in Theodore Roosevelt National Park [29] and in central and eastern Montana [30]. Marsh muhly occurred sporadically in the green ash-American elm community type in western North Dakota [87]. At the Niobrara Valley Preserve, Nebraska, marsh muhly is a species of wide distribution in the basswood-eastern redcedar-eastern hophornbeam-green ash (Tilia americana-Juniperus virginiana-Ostrya virginiana-Fraxinus pennsylvanica) association in narrow, spring-fed canyons [31]. Marsh muhly occurred in the quaking aspen/water birch (Betula occidentalis) habitat type on upper slopes at Theodore Roosevelt National Park [29] and the quaking aspen/Oregon-grape (Berberis repens) habitat type in the Custer National Forest in North Dakota [28].

Marsh muhly sometimes occurs in shrub-dominated communities, such as disturbed and/or early- to midseral stands of the silver sagebrush/western wheatgrass (Artemisia cana/Pascopyrum smithii) habitat type in central and eastern Montana [30] and in Theodore Roosevelt National Park [29]. This type represents one of the driest extremes of the riparian or wetland zone and is a disturbance-caused disclimax where site potential has changed due to heavy prolonged grazing. Sites are located in deep, loamy, alluvial soils or where overland flow and/or fine-textured soils allow for increased moisture availability. Marsh muhly occasionally occurs in other shrub-dominated community types representing grazing disclimaxes, including the chokecherry, Wood's rose (Rosa woodsii), and western snowberry community types. Kentucky bluegrass dominates the herb layer in these types [30]. In southern Saskatchewan marsh muhly occurred with ≤1% canopy cover in mixed-shrub and western snowberry communities, but reached 1.4% canopy cover in the silver buffaloberry community on alluvial deposits [51].

While marsh muhly is typically found in lowland sites in the Northern Plains, it also occurs in relatively drier upland communities. In the loessial region of northwestern Kansas and southwestern Nebraska, for example, marsh muhly was most common in lowland sites (32.5% absolute frequency), but it also occurred on level uplands, gentle upper slopes, and gentle lower slopes with <1% absolute frequency. It did not occur on steep slopes. It was most common on mesic sites (6.92% of the community composition and 0.33% basal cover), rarely occurred on dry-mesic sites (0.18% composition, 0.01% basal cover), and did not occur on dry or very dry sites [40]. It was recorded in tallgrass prairie sites in western Nebraska [39] and South Dakota [33]. At the Loess Hills Wildlife Area, Iowa, marsh muhly occurred in the aboveground vegetation and the soil seed bank in deciduous woodland and shrubland communities dominated by roughleaf dogwood (Cornus drummondii) and elms (Ulmus spp.). It also occurred in the soil seed bank in both native tallgrass (dominated by big bluestem and indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans)) and midgrass (dominated by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula)) grasslands and nonnative grasslands (dominated by Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome (Bromus inermis)) in the area. It was either rare, absent, or not sampled in aboveground vegetation in these grassland communities [67]. Marsh muhly occurred sporadically in the bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) community type in western North Dakota [87]. It occurred in one stand of the needle-and-thread grass/sedge (Hesperostipa comata-Carex) habitat type in southwestern North Dakota on gently rolling slopes of sandy uplands [34]. Marsh muhly was found in the soil seed bank in grasslands dominated by blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), marsh needlegrass (Nassella viridula), needle-and-thread grass, prairie sandreed (Calamovilfa longifolia), and western wheatgrass at Theodore Roosevelt National Park [80].

Northern and Central Rockies: According to Rydberg [68], marsh muhly occurs in wet meadows in the subalpine and montane zones throughout the Rocky Mountains. However, publications describing habitats or site conditions for marsh muhly in the Northern and Central Rocky Mountains are lacking. One study noted marsh muhly among the pioneer vegetation 5 years after a severe fire in a subalpine fir/grouse whortleberry (Abies lasiocarpa/Vaccinium scoparium) habitat type in Yellowstone National Park [1]. Marsh muhly occurred in disturbed and/or early- to midseral stands of the silver sagebrush/western wheatgrass habitat type, which occurs at 5,600 feet (1,697 m) throughout central and eastern Idaho. Site conditions in this habitat type (e.g., deep, fine-textured soils, and/or periods of overland flow) increase moisture availability and sometimes result in a perched water table [25]. According to a flora of the Intermountain West, marsh muhly is infrequent in the area and occurs on dry ground such as drying meadows, rocky slopes, and in disturbed sites such as irrigation ditches and cultivated areas [9]. In riparian communities along the lower Yellowstone River, Montana, marsh muhly occurred at all stages of succession described as seedling, thicket, young cottonwood, mature cottonwood, shrub, and grassland stages. It also occurred in willow (Salix spp.)-shrub and green ash communities [6]. Marsh muhly occurred in ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) forest on the Custer National Forest in southeastern Montana [42].

Southwest: Marsh muhly may occur in dry microsites in the Southwest but is most often described in moist microsites and riparian communities. For example, Colorado floras describe marsh muhly sites as rocky places in the sagebrush (Artemisia spp.) and quaking aspen zones [88] or rocky slopes, foothills, plains, gulches, and the bases of cliffs [89]. One study notes that marsh muhly occurred only on cliffs in their study area in the Colorado Front Range [23]. Another study in the foothills of the Colorado Front Range recorded marsh muhly in a mesophytic grassland association where it was commonly scattered along the moist soil of stream margins in open situations [83]. Marsh muhly is considered a wetland indicator species in New Mexico [60].

A study from the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument along the Gunnison River in Colorado demonstrates marsh muhly's wide tolerance for soil moisture conditions. Marsh muhly was a dominant species in the cover type with intermediate soil moisture conditions. On flat areas of alluvial sediment along the river, 3 cover types were identified on the basis of species-occurrence data. These cover types differed in both inundation duration and soil particle size (P<0.0001). Marsh muhly was a codominant species in the scouringrush horsetail (Equisetum hyemale) cover type, which consisted of mesic to xeric herbs and grasses dominated by scouringrush horsetail, Canada bluegrass, creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera), marsh muhly, and western goldentop (Euthamia occidentalis). The substrate was primarily organic matter and sands; however, some plots were dominated by boulders. This cover type was typically found on middle and upper elevation gravel and cobble bars and was a relatively dry and infrequently inundated cover type. Marsh muhly also occurred in 57% of the plots in the common spikerush (Eleocharis palustris) cover type. This was the wettest cover type and was found from the channel edge up to low and middle elevation gravel bars and was frequently inundated. The substrate was variable and consisted primarily of cobbles and boulders with large fractions of silt, sand, and organic matter. Marsh muhly occurred in only 7% of the plots in the hairy false goldenaster (Heterotheca villosa) cover type, which consisted of largely of upland species and xeric grasses and was dominated by cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), hairy false goldenaster, and sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus). This was the driest, least frequently inundated cover type, and had a substrate that was primarily sands, cobbles, and boulders. Marsh muhly was classified as a facultative upland species (1-33% occurrence in wetlands) [2], which is more consistent with its classification in the Intermountain Region, but not the Southwest [82].

Marsh muhly occurs in riparian forests throughout the Southwest, including both narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) and boxelder community types in southern Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. The narrowleaf cottonwood community type occurs at elevations ranging from 5,439 to 9,199 feet (1,658-2,804 m), and the boxelder community type occurs at elevations ranging from 4,879 to 7,119 feet (1,487-2,170 m) [78]. In northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, marsh muhly can occur in riparian forests in the narrowleaf cottonwood-Rocky Mountain juniper/sand dropseed (Juniperus scopulorum/Sporobolus cryptandrus) community type, which is characterized by mature, moderately open stands (40-60% cover). This community type occupies some of the driest sites in the floodplain, occurring mostly on sandy alluvial sediments; however, wetland indicator species such as marsh muhly, common rush (Juncus effusus), and fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata) can occur [60].

Marsh muhly has been reported in a variety of other riparian types in the Southwest. For example, marsh muhly occurs in the narrowleaf willow/false quackgrass (Salix exigua/Elymus × pseudorepens) community type, which is associated with low-gradient rivers at elevations around 6,000 feet (1,825 m) in the upper Rio Grande watershed in New Mexico. This shrub community is dominated by moderate to dense canopies of narrowleaf willow with abundant false quackgrass in the understory. The nonnative saltcedar (Tamarix ramosissima) may be well represented but is not dominant. Soils are loamy or sandy-skeletal and are normally wet within 1.6 feet (0.5 m) of the surface [60]. Marsh muhly occurs with <1% cover and 25% constancy in the semiriparian ponderosa pine/Arizona walnut (Juglans major) habitat type, which occurs sporadically on alluvial terraces along perennial streams or large washes south of the Mogollon Rim in Arizona at elevations between 5,500 and 6,400 (1,680 and 1,950 m) [59]. At Wide Rock Butte in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona, marsh muhly occurred only in the one developed drainage. This area had deep soil (>3.3 feet (1m)) and dense vegetation consisting of prairie sage (Artemisia ludoviciana) and other forbs and grasses. The surrounding vegetation is a pinyon-juniper (Pinus-Juniperus) type [69].

Great Basin: Marsh muhly is rare in the Great Basin, apparently occurring in both dry and wet habitats. According to Kartesz [45], marsh muhly occurs in moist areas in canyons and meadows along streams and ditches at 3,500 to 5,500 feet (1,100-1,700 m). However, it is rare in Nevada and known only from the Ruby Mountains [45]. A habitat type publication from Nevada identifies marsh muhly as a component of the Wood's rose shrubland, which is said to occur in the foothills and plains of Montana, Idaho, Nevada, and eastern California, although no plots of this community type have been identified in Nevada [63]. The Utah flora indicates that marsh muhly occurs on dry to moist sites on open slopes, in hanging gardens, mountain brush, aspen, ponderosa pine, and meadow communities at 4,000 to 10,000 feet (1,220-3,050 m). It is also a weed of gardens [90]. A flora from the Uinta Basin, Utah, identifies 2 records of marsh muhly from dry, rocky slopes at 7,160 to 7,500 feet (2,180-2,280 m) [22].

Northwest: Marsh muhly's occurrence in the Northwest is confusing. One publication notes its occurrence in marl fen at the extreme northern part of Pend Oreille County, Washington [52]. However, floras from the Pacific Northwest suggest that while marsh muhly may occur on moist streambanks, irrigation ditches, and lake margins, it mainly occurs in dry, often rocky areas [37]. In fact, they distinguish marsh muhly from spiked muhly based on habitat: marsh muhly occurs on dry upland and disturbed sites, and spiked muhly occurs in moist areas [36].

Northeast: Information on marsh muhly site preferences in the Northeast comes exclusively from regional floras. Marsh muhly is said to occur on dry soil in New England [72], and is reported to occur in drier habitats than spiked muhly. Potential habitats include prairies, rock outcrops, open upland woods [21], meadows, rocky slopes, river shores, and occasionally wet meadows [55]. It may also occur along roads or in other disturbed sites [21] or "waste places" [55].

Marsh muhly is a perennial, rhizomatous grass [5,9,24,58,77,88,90]. Culms are 12 to 51 inches (30-130 cm) tall, 1 to 1.5 mm thick, mostly erect, and commonly branched at or above the middle nodes [5,35,37,50,77]. Stems may be decumbent [50] or reclining [8]. Internodes are mostly smooth and glabrous [5,24,35,86]. Leaf blades are mostly flat, 0.8 to 7 inches (2-18 cm) long and 2 to 7 mm wide [5,9,24,50,58,77], erect or ascending [58,77]. Fruits are caryopses 1.2 to 2.3 mm long [5,9] and borne in narrow, compact panicles 0.3 to 6 inches (0.8-16 cm) long and 0.1 to 0.7 inch (0.3-1.8 cm) wide [5,8,24,35,37,50,58,77]. Glumes are awned; lemmas may be awned or unawned [5].

Marsh muhly is described as strongly rhizomatous [24], and rhizomes are variously described as long [9,90], scaly [8,9,35,58,77,88,90], creeping [8,9,35], branching [35,77], stout [8], and very tough [47].

Marsh muhly differs morphologically from spiked muhly in internode pubescence [37,50,64], ligule length [37,64], anther length, lemma pubescence [64], and location of branching [37]. Marsh muhly is also described as more robust [50], with culms and rhizomes usually somewhat stouter than those of spiked muhly [35].

Raunkiaer [66]

life form:

Hemicryptophyte

Geophyte

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

Marsh muhly is a warm-season grass that begins growing in late spring and flowers from mid-summer until fall [77]. Flowering dates vary by area.

| Flowering dates reported for marsh muhly by area | |

| Area | Dates |

| Illinois, Sand Ridge State Forest | August-September [56] |

| Nebraska, Pine Ridge | 25 July [62] |

| New Mexico | July-September [58] |

| Nevada | July-September [45] |

| Utah, Uinta Basin | July-September [22] |

| Great Plains | July-October [24] |

| Intermountain area | July-September [9] |

| New England | 26 August-11 September [72] |

| Northeastern United States | August-September [55] |

| Northern Great Plains | Late July-October [50] |

| Pacific Northwest | August-September [37] |

A study conducted in the transition zone between an old field and native prairie in Jefferson County, Kansas, reported marsh muhly seed rain from mid-September through early December. Seed rain was greatest from late October through early December [70]. It is not clear whether marsh muhly occurred in the old field, prairie, or both.

| Number of marsh muhly seeds collected in seed traps in Jefferson County, Kansas, between 17 September and 11 December 1992. No seeds were trapped between 10 June and 3 September [70]. | ||||||||

| Date | 9/17 |

10/1 |

10/15 |

10/29 |

11/14 |

11/29 |

12/11 |

Total |

| Number of seeds | 1 |

12 |

14 |

20 |

25 |

22 |

24 |

118 |

Pollination and breeding system: No information is available on this topic.

Seed production: No information is available on this topic.

Seed dispersal: No information was found on this topic in the available literature (as of 2011). However, because seeds lack appendages to aid in long-distance dispersal by wind or animals, most marsh muhly seeds are probably dispersed by gravity in the area near the parent plant. Longer distance dispersal may be aided by awns on glumes and lemmas before seed is released from the panicle.

Seed banking: The limited available evidence as of this writing (2011) suggests that marsh muhly seeds are likely to occur in the soil seed bank in areas where marsh muhly occurs in the aboveground vegetation, but duration of the seed's persistence is unclear. At the Loess Hills Wildlife Area, Iowa, marsh muhly was among the 9 or 10 most abundant species in the soil seed bank in 3 of the 5 communities sampled. Marsh muhly seed density was greatest in deciduous shrubland communities. It was present but not abundant in the aboveground vegetation of the woodland and shrubland communities, and it was either rare, absent, or not sampled in aboveground vegetation in grassland communities [67].

| Marsh muhly density in the soil seed bank in 5 communities in the Loess Hills Wildlife Area, Iowa [67] | ||

| Community type | Mean seed density (seeds/m²) | Relative seed bank density (%) |

| Deciduous woodland | 28.8 | 2.1 |

| Deciduous shrubland | 97.8 | 7.7 |

| Nonnative grassland | 45.8 | 3.1 |

| Tallgrass community | 18.3 | ---* |

| Midgrass community | 3.1 | --- |

| *Data not given. | ||

Marsh muhly occurred in the soil seed bank in grasslands managed with prescribed fire at Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Total number of marsh muhly seedlings germinating in the greenhouse ranged from 10 to 16 seedlings/m² in soil samples collected to a depth of 2 inches (5 cm). No information regarding marsh muhly abundance in the aboveground vegetation was given. See Fire adaptations for more details [80]. Marsh muhly was present in both the aboveground vegetation and the seed bank of an agricultural field in southwestern Ohio that was abandoned in 1950, mowed regularly through the late 1970s, grazed by livestock until 1998, and then designated for ecological restoration research. Soil cores were taken to a depth of 6 inches (15 cm) in March 2000. No details regarding marsh muhly abundance in the seed bank or aboveground vegetation were given [53].

Germination: Only one study addressing germination in marsh muhly was found in the literature available as of 2011. Germination percentages of marsh muhly in the greenhouse ranged from 18% to 52% 30 days after sowing. Stratification at 39 °F (4 °C) for 2 to 4 weeks did not seem to affect germination [7].

Seedling establishment and plant growth: No information is available on this topic.

Plant growth: The only information available regarding growth of marsh muhly (as of 2011) indicated that it responded favorably to fertilizer additions in plots with mixed-grass species in a native oak savanna in eastern Minnesota. Plots receiving experimental fertilization over a 16-year period had dramatic changes in vegetation. Fertilization treatments included 2 levels of nitrogen addition and addition of background levels of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur, and trace metals. In unfertilized plots, 5 species had over 40%; these did not include marsh muhly. In the 5.4 g nitrogen/m²/year treatment, 4 plant species had over 40% cover including marsh muhly. In the 17 g nitrogen/m²/year treatment, only marsh muhly had over 40% cover, and it had the highest cover of any species in any treatment (66%) [3].

Vegetative regeneration:

Marsh muhly is rhizomatous [5,9,24,58,77,88,90]. No additional information was available on this topic as of 2011.

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

While marsh muhly is often described as a ruderal plant, occurring in recently and repeatedly disturbed sites (e.g., [50,56]), it does not seem to be confined to any particular stage of succession in most of the plant communities in which it occurs. It also seems to tolerate a wide range of light conditions from shady to sunny, occurring under dense canopies (e.g., [20,51,59,78]) and in open grasslands and wetlands (e.g., [71,83]).

Based on a review of pertinent literature and observations by ecologists in southern Wisconsin, Bader [4] suggests that marsh muhly tolerates only partial shade to full sun. However, Larson [50] suggests that marsh muhly often occurs in shady sites. Additionally, marsh muhly is often found under relatively dense canopies. For example, marsh muhly occurred in the silver buffaloberry community in southern Saskatchewan, where total canopy cover averaged 226% [51]. Marsh muhly occurs in the semiriparian ponderosa pine/Arizona walnut habitat type in Arizona, which has closed canopies [59]. Throughout the Southwest, marsh muhly occurs in riparian forests dominated by boxelder or narrowleaf cottonwood where overstory cover averages 78.8% to 80.7%, respectively [78]. Marsh muhly was among the dominant understory species in relatively undisturbed, deciduous forests with closed canopies in Iowa [20].

Stubbendieck and others indicate that marsh muhly is an increaser [75] that rapidly occupies disturbed areas [77]. Studies of succession in various habitats tend to support the idea that marsh muhly is an early-successional species, but it is unclear how long it might persist and whether this varies among the wide range of plant communities in which it occurs. For example, marsh muhly was among the pioneer species 5 years after a severe fire in climax vegetation in a subalpine fir/grouse whortleberry habitat type in Yellowstone National Park [1]. Marsh muhly did not occur in a tamarack bog in Minnesota when the canopy was dense in 1946. However, marsh muhly was present in 1952 after many of the small trees had died, likely due to a rise in the water table. The authors speculated that it established in response to increased light; however, in 1957, standing and fallen dead trees resulted in a canopy that was "quite open", and marsh muhly no longer occurred on the site [41]. In a study of plant succession following the drainage of 2 lakes in northern Minnesota in 1924, marsh muhly was among several "wet soil species" occurring in 1934 in fine soils at the edge of a "delta" that formed when the lakes drained. Marsh muhly was also among the sparse, scattered plants in the understory of paper birch (Betula papyrifera) on talus slopes and old cobble and boulder beaches from 1934 to 1939. It also occurred in the drier portions of drained peat under a dense stand of quaking aspen [61]. Marsh muhly was a characteristic species in both undisturbed and burned western bracken fern-grasslands in northeastern Wisconsin [84,85]. In Dane County, Wisconsin, marsh muhly was a minor component in peatlands undergoing succession in an area around a small, receding lake, and in a hay meadow from which tamarack had been removed by grubbing. It was more widespread, though still relatively infrequent, in a drained, reedgrass-sedge community succeeding to a big bluestem-dominated community [19]. Marsh muhly was relatively abundant (40% cover) in disturbed and/or early to midseral stands of boxelder/chokecherry habitat types in central and eastern Montana [30].

Studies of succession in areas where marsh muhly occurs lack sufficient information on marsh muhly for understanding its successional role. In a chronosequence study along the Missouri River in southeastern South Dakota, marsh muhly occurred in stands of eastern cottonwood that were 23 to 35 years old, but did not occur in 10-year-old, 14-year-old, or 55-year-old stands [92]. In riparian communities along the lower Yellowstone River, Montana, marsh muhly occurred at all stages of succession, including those described as seedling, thicket, young cottonwood, mature cottonwood, shrub, and grassland [6]. On the Custer National Forest in southeastern Montana, marsh muhly occurred but was infrequent in stands of sapling-sized ponderosa pine; however, it did not occur in stands composed of pole- or sawlog-sized ponderosa pine [42].

Marsh muhly seems to persist and may increase with grazing. It was among the most abundant species in riparian habitats in north-central Kansas which, by the mid 1990s, were restricted to narrow bands of deciduous forest. Since the late 1970s, several riparian exclosures had been constructed to exclude cattle grazing from riparian habitats, but the exclosures were not maintained, resulting in continued grazing at unregulated intensities. In 1996, 3 exclosures were repaired and locked, and vegetation was compared between ungrazed exclosures and grazed study sites. Marsh muhly cover in grazed sites was similar in 1996 (6.18%) and 1997 (6.44%). Cover decreased on ungrazed sites from 13.0% in 1996 to 2.86% in 1997; the difference between grazed and ungrazed sites in 1997 was not significant [38]. In Montana, marsh muhly was more abundant in eastern cottonwood community types considered grazing or browsing disclimaxes than in eastern cottonwood communities that were relatively undisturbed by livestock or wildlife [30]. Marsh muhly also occurs in shrub-dominated communities that represent grazing disclimaxes, such as disturbed stands of the silver sagebrush/western wheatgrass habitat type in central and eastern Montana [30] and Theodore Roosevelt National Park [29]; and the chokecherry, Wood's rose, and western snowberry community types in central and eastern Montana [30].

Immediate fire effect on plant:

No information was available regarding the immediate effects of fire on marsh muhly as of 2011. Marsh muhly is likely top-killed by fire, and anecdotal information suggests that marsh muhly rhizomes and seeds likely survive fire. However, it is unclear whether a severe fire is likely to kill rhizomes and seeds. Information is needed regarding heat tolerance of marsh muhly seeds and depth of marsh muhly rhizomes and seeds in the soil profile.

Postfire regeneration strategy [74]:

Rhizomatous herb, rhizome in soil

Ground residual colonizer (on site, initial community)

Fire adaptations: No information was available regarding fire adaptations in marsh muhly as of 2011. Limited experimental evidence suggests that marsh muhly can persist or increase after fire [15,16,84,85]. Anecdotal information from studies noting marsh muhly occurrence after fire or presence on frequently burned sites suggests that marsh muhly rhizomes and seeds are likely to survive and sprout or germinate after fire, or that marsh muhly may establish from off-site seed sources (see below).

Plant response to fire: It appears that marsh muhly may establish, persist, or increase after fire. However, this generalization is tentative because very few studies compared postfire abundance of marsh muhly with prefire abundance [15,16,84,85], and important details of other postfire observations (e.g., [1,14,46]) are lacking.

Marsh muhly may establish after fire. It was among the pioneer vegetation 5 years after a severe fire in climax vegetation in a subalpine fir/grouse whortleberry habitat type in Yellowstone National Park. It occurred with 4.28% cover in 1 of the 3 stands examined [1]. It is not clear whether marsh muhly occurred before the fire or whether it established from on-site or off-site sources.

Marsh muhly seems to persist or increase after fire in plant communities adapted to frequent fire in Wisconsin. In northern pine-hardwood communities that arose with fire exclusion beginning in the early 1900s in Crex Meadows, Wisconsin, vegetation in 28 burned stands and 9 unburned control stands was surveyed. The area was managed with prescribed fire from 1947 until 1958, with an average of 3.5 fires per stand. Fires were generally set in March or April, and sampling was done in late June, July, and August of each year from 1958 to 1961. Of the 28 burned stands, 20 were sampled the summer following the last spring fire, and 8 were sampled 1 or 2 years after fire. Marsh muhly was classified as an increaser in these communities, because its average frequency in burned stands was 5.1% greater than its average frequency in unburned stands [85]. Marsh muhly was classified as fire neutral in undisturbed western bracken fern-grasslands in northeastern Wisconsin, because its average frequency differed by less than 5% between burned and unburned areas. Its average frequency was 14.2% in unburned bracken-grasslands and 17.7% in burned bracken-grasslands (averaged across several burned areas with variable fire histories) [84,85].

Anecdotal observations of marsh muhly presence in areas with a history of fire suggest that marsh muhly may tolerate frequent fires. However, information regarding time of establishment was not provided, making conclusions speculative at best. For example, in northeastern Kansas, marsh muhly occurred on a native prairie remnant that was managed with spring prescribed fires every 1 to 3 years. It did not occur on an adjacent restoration area that was previously farmed, disked, and planted with a commercial warm-season grass mixture, or on a prairie remnant that was managed with annual haying [46]. Marsh muhly did not occur in Kalsow Prairie Preserve, Iowa, in 1950 but occurred at 7.1% average frequency in 1999/2000, after 50 years of periodic burning in April [14]. Marsh muhly occurred in a native oak savanna maintained by 2 prescribed fires every 3 years in eastern Minnesota [3]. Cover of marsh muhly was not correlated with fire frequency in oak forest in east-central Minnesota, based on comparisons between 3 unburned sites and 9 sites burned with varying frequencies (2 to 19 fires in a 20-year period) [79].

Fire may stimulate reproduction in marsh muhly. Marsh muhly seedstalks occurred with 35% frequency in an area of Hayden Prairie, Iowa, that was burned annually for 3 consecutive years, but none were recorded in unburned areas or areas burned 1 to 2 years previously [15,16]. In a related study, marsh muhly seedstalks occurred with 30% frequency after a single prescribed fire in 1956, but none were recorded on an adjacent unburned area [15]. Because only seedstalks were counted, it is unclear whether non-flowering marsh muhly individuals occurred on the unburned and less frequently burned areas at Hayden Prairie. That seems likely, however, because marsh muhly was reported to be one of the most important grasses in the prairie [15,16].

Marsh muhly seeds may survive fire. Marsh muhly occurred in the soil seed bank in grasslands managed with prescribed fire at Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Sites were burned in October 2001, and soil samples were collected to a depth of 2 inches (5 cm) in spring 2002. Based on seedling emergence from these samples, density of marsh muhly seeds was estimated at 10 to 16 seeds/m², suggesting at least short-term persistence in the soil seed bank and survival after fire [80].

FUELS AND FIRE REGIMES:

Fuels:

No information was available regarding fuel characteristics of marsh muhly as of 2011.

Fire regimes: No information was available (as of 2011) specifically addressing marsh muhly responses to various fire regime characteristics. As a warm-season grass, marsh muhly is likely to be more tolerant of early spring fires than late spring or summer fires (e.g., see [32]). Marsh muhly has been noted on several sites subjected to frequent fires (e.g., [3,15,16,46]), suggesting that it may tolerate a regime of periodic burning (see Plant response to fire for further details on these studies). However, information regarding marsh muhly abundance or time of establishment relative to individual fires or specific fire regimes is lacking, making it impossible to predict its response in a given plant community under a given fire regime.

Marsh muhly occurs in a variety of plant communities with a range of presettlement fire regime characteristics, suggesting that it may tolerate a variety of fire regimes. For example, it occurs in grassland and prairie communities characterized by predominantly frequent-interval, replacement fire regimes; subalpine communities characterized by long-interval, replacement fire regimes; and savanna communities characterized by predominantly frequent-interval, surface fire regimes. Marsh muhly commonly occurs in wetland and riparian communities which are characterized by a variety of replacement and mixed-severity fire regimes of varying frequency. See the Fire Regime Table for additional information on fire regimes of vegetation communities in which marsh muhly may occur. Find further fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes".

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

None

OTHER STATUS:

None

IMPORTANCE TO WILDLIFE AND LIVESTOCK:

As of this writing (2011) little information was available specifically addressing the importance of marsh muhly to wildlife, although Stubbendieck and others [77] suggest that marsh muhly is poor forage for wildlife.

Marsh muhly may be a component in plant communities used by wildlife, though its relative importance is unclear. For example, marsh muhly is a component of the green ash/western snowberry habitat type in Theodore Roosevelt National Park, which is used by bison for grazing, watering, and shade [29].

Apparently marsh muhly is used by livestock to some degree, and it may be a component of habitats used by livestock (e.g., [59]). However, it does not seem to be an important component of livestock diets. Marsh muhly was eaten sparingly by cows in a ponderosa pine forest in the northern Black Hills, South Dakota [81]:

| Average contribution (%) of marsh muhly to cattle diets in the northern Black Hills [81] | |||

June |

July |

August |

September |

3.2 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

1.7 |

In a publication on economic grasses from 1900, marsh muhly was said to be "little prized in the East" but was recommended as an excellent grass for hay in the northwestern states [47]. Conversely, Stubbendieck and others [77] suggest that the value of hay is reduced by its presence. They indicate that palatability of marsh muhly is fair to good before maturity, and its value decreases rapidly with maturity. When immature, it is said to provide fair forage for cattle but poor forage for domestic sheep [75,77]. Marsh muhly forage value for livestock and wildlife was rated by Dittberner and Olson as follows [11]:

| Animal | State |

||

| Colorado | North Dakota | Utah |

|

| Cattle | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Sheep | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Horses | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Pronghorn | ---* | --- | Poor |

| Elk | --- | --- | Fair |

| Mule deer | --- | --- | Fair |

| Small mammals | --- | --- | Fair |

| Small nongame birds | --- | --- | Fair |

| Upland game birds | --- | --- | Poor |

| *No information. | |||

Nutritional value: Marsh muhly is rated fair in energy value and poor in protein value [11].

Cover value: In Utah, cover value of marsh muhly is rated as poor for upland game birds and fair for small mammals and small nongame birds [11].

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

No information is available on this topic.

OTHER USES:

No information is available on this topic.

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

No information is available on this topic.

| Fire regime information on vegetation communities in which marsh muhly may occur. This information is taken from the LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment Vegetation Models [49], which were developed by local experts using available literature, local data, and/or expert opinion. This table summarizes fire regime characteristics for each plant community listed. The PDF file linked from each plant community name describes the model and synthesizes the knowledge available on vegetation composition, structure, and dynamics in that community. Cells are blank where information is not available in the Rapid Assessment Vegetation Model. | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Marsh | Replacement | 74% | 7 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 26% | 20 | ||||||||||

| Southwest | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Southwest Grassland | ||||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie | Replacement | 87% | 12 | 2 | 35 | |||||||

| Mixed | 13% | 80 | ||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie with shrubs | Replacement | 80% | 15 | 2 | 35 | |||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 60 | ||||||||||

| Shortgrass prairie with trees | Replacement | 80% | 15 | 2 | 35 | |||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 60 | ||||||||||

| Montane and subalpine grasslands | Replacement | 55% | 18 | 10 | 100 | |||||||

| Surface or low | 45% | 22 | ||||||||||

| Montane and subalpine grasslands with shrubs or trees | Replacement | 30% | 70 | 10 | 100 | |||||||

| Surface or low | 70% | 30 | ||||||||||

| Southwest Woodland | ||||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine/grassland (Southwest) | Replacement | 3% | 300 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 97% | 10 | ||||||||||

| Southwest Forested | ||||||||||||

| Riparian forest with conifers | Replacement | 100% | 435 | 300 | 550 | |||||||

| Riparian deciduous woodland | Replacement | 50% | 110 | 15 | 200 | |||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 275 | 25 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 30% | 180 | 10 | |||||||||

| Ponderosa pine-Gambel oak (southern Rockies and Southwest) | Replacement | 8% | 300 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 92% | 25 | 10 | 30 | ||||||||

| Stable aspen without conifers | Replacement | 81% | 150 | 50 | 300 | |||||||

| Surface or low | 19% | 650 | 600 | >1,000 | ||||||||

| Great Basin | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Mountain meadow (mesic to dry) | Replacement | 66% | 31 | 15 | 45 | |||||||

| Mixed | 34% | 59 | 30 | 90 | ||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Grassland | ||||||||||||

| Northern prairie grassland | Replacement | 55% | 22 | 2 | 40 | |||||||

| Mixed | 45% | 27 | 10 | 50 | ||||||||

| Mountain grassland | Replacement | 60% | 20 | 10 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 40% | 30 | ||||||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Shrubland | ||||||||||||

| Riparian (Wyoming) | Mixed | 100% | 100 | 25 | 500 | |||||||

| Mountain shrub, nonsagebrush | Replacement | 80% | 100 | 20 | 150 | |||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 400 | ||||||||||

| Mountain big sagebrush steppe and shrubland | Replacement | 100% | 70 | 30 | 200 | |||||||

| Northern and Central Rockies Forested | ||||||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Northern Great Plains) | Replacement | 5% | 300 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 20% | 75 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 75% | 20 | 10 | 40 | ||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Black Hills, low elevation) | Replacement | 7% | 300 | 200 | 400 | |||||||

| Mixed | 21% | 100 | 50 | 400 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 71% | 30 | 5 | 50 | ||||||||

| Ponderosa pine (Black Hills, high elevation) | Replacement | 12% | 300 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 18% | 200 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 71% | 50 | ||||||||||

| Lower subalpine (Wyoming and Central Rockies) | Replacement | 100% | 175 | 30 | 300 | |||||||

| Upper subalpine spruce-fir (Central Rockies) | Replacement | 100% | 300 | 100 | 600 | |||||||

| Northern Great Plains | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Northern Plains Grassland | ||||||||||||

| Nebraska Sandhills prairie | Replacement | 58% | 11 | 2 | 20 | |||||||

| Mixed | 32% | 20 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 10% | 67 | ||||||||||

| Northern mixed-grass prairie | Replacement | 67% | 15 | 8 | 25 | |||||||

| Mixed | 33% | 30 | 15 | 35 | ||||||||

| Southern mixed-grass prairie | Replacement | 100% | 9 | 1 | 10 | |||||||

| Central tallgrass prairie | Replacement | 75% | 5 | 3 | 5 | |||||||

| Mixed | 11% | 34 | 1 | 100 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 13% | 28 | 1 | 50 | ||||||||

| Northern tallgrass prairie | Replacement | 90% | 6.5 | 1 | 25 | |||||||

| Mixed | 9% | 63 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 2% | 303 | ||||||||||

| Southern tallgrass prairie (East) | Replacement | 96% | 4 | 1 | 10 | |||||||

| Mixed | 1% | 277 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 3% | 135 | ||||||||||

| Oak savanna | Replacement | 7% | 44 | |||||||||

| Mixed | 17% | 18 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 76% | 4 | ||||||||||

| Northern Plains Woodland | ||||||||||||

| Oak woodland | Replacement | 2% | 450 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 98% | 7.5 | ||||||||||

| Northern Great Plains wooded draws and ravines | Replacement | 38% | 45 | 30 | 100 | |||||||

| Mixed | 18% | 94 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 43% | 40 | 10 | |||||||||

| Great Plains floodplain | Replacement | 100% | 500 | |||||||||

| Great Lakes | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| Great Lakes Grassland | ||||||||||||

| Mosaic of bluestem prairie and oak-hickory | Replacement | 79% | 5 | 1 | 8 | |||||||

| Mixed | 2% | 260 | ||||||||||

| Surface or low | 20% | 2 | 33 | |||||||||

| Great Lakes Woodland | ||||||||||||

| Great Lakes pine barrens | Replacement | 8% | 41 | 10 | 80 | |||||||

| Mixed | 9% | 36 | 10 | 80 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 83% | 4 | 1 | 20 | ||||||||

| Northern oak savanna | Replacement | 4% | 110 | 50 | 500 | |||||||

| Mixed | 9% | 50 | 15 | 150 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 87% | 5 | 1 | 20 | ||||||||

| Great Lakes Forested | ||||||||||||

| Conifer lowland (embedded in fire-prone ecosystem) | Replacement | 45% | 120 | 90 | 220 | |||||||

| Mixed | 55% | 100 | ||||||||||

| Conifer lowland (embedded in fire-resistant ecosystem) | Replacement | 36% | 540 | 220 | >1,000 | |||||||

| Mixed | 64% | 300 | ||||||||||

| Great Lakes floodplain forest | Mixed | 7% | 833 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 93% | 61 | ||||||||||

| Oak-hickory | Replacement | 13% | 66 | 1 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 11% | 77 | 5 | |||||||||

| Surface or low | 76% | 11 | 2 | 25 | ||||||||

| South-central US | ||||||||||||

| Vegetation Community (Potential Natural Vegetation Group) | Fire severity* | Fire regime characteristics | ||||||||||

| Percent of fires | Mean interval (years) |

Minimum interval (years) |

Maximum interval (years) |

|||||||||

| South-central US Grassland | ||||||||||||

| Southern shortgrass or mixed-grass prairie | Replacement | 100% | 8 | 1 | 10 | |||||||

| Oak savanna | Replacement | 3% | 100 | 5 | 110 | |||||||

| Mixed | 5% | 60 | 5 | 250 | ||||||||

| Surface or low | 93% | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| *Fire Severities— Replacement: Any fire that causes greater than 75% top removal of a vegetation-fuel type, resulting in general replacement of existing vegetation; may or may not cause a lethal effect on the plants. Mixed: Any fire burning more than 5% of an area that does not qualify as a replacement, surface, or low-severity fire; includes mosaic and other fires that are intermediate in effects. Surface or low: Any fire that causes less than 25% upper layer replacement and/or removal in a vegetation-fuel class but burns 5% or more of the area [27,48]. |

||||||||||||

1. Ament, Robert J. 1995. Pioneer plant communities five years after the 1988 Yellowstone fires. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 216 p. Thesis. [46923]

2. Auble, Gregor T.; Friedman, Jonathan M.; Scott, Michael L. 1994. Relating riparian vegetation to present and future streamflows. Ecological Applications. 4(3): 544-554. [82476]

3. Avis, Peter G.; McLaughlin, David J.; Dentinger, Bryn C.; Reich, Peter B. 2003. Long-term increase in nitrogen supply alters above- and below-ground ectomycorrhizal communities and increases the dominance of Russula spp. in a temperate oak savanna. New Phytologist. 160(1): 239-253. [82471]

4. Bader, Brian J. 2001. Developing a species list for oak savanna/oak woodland restoration at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum. Ecological Restoration. 19(4): 242-250. [82468]

5. Barkworth, Mary E.; Capels, Kathleen M.; Long, Sandy; Piep, Michael B., eds. 2003. Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 25: Magnoliophyta: Commelinidae (in part): Poaceae, part 2. New York: Oxford University Press. 814 p. [68091]

6. Boggs, Keith Webster. 1984. Succession in riparian communities of the lower Yellowstone River, Montana. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. 107 p. Thesis. [7245]

7. Bohnen, Julia L. 1994. Seed production and germination of native prairie plants. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota. 109 p. Thesis. [51407]

8. Booth, W. E. 1950. Flora of Montana. Part I: Conifers and monocots. Bozeman, MT: The Research Foundation at Montana State College. 232 p. [48662]

9. Cronquist, Arthur; Holmgren, Arthur H.; Holmgren, Noel H.; Reveal, James L.; Holmgren, Patricia K. 1977. Intermountain flora: Vascular plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Vol. 6: The Monocotyledons. New York: Columbia University Press. 584 p. [719]

10. Curtis, John T. 1959. Prairie. In: The vegetation of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press: 261-307. [60526]

11. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The Plant Information Network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

12. Dorn, Robert D. 1984. Vascular plants of Montana. Cheyenne, WY: Mountain West Publishing. 276 p. [819]

13. Dorn, Robert D. 1988. Vascular plants of Wyoming. Cheyenne, WY: Mountain West Publishing. 340 p. [6129]

14. Dornbush, Mathew E. 2004. Plant community change following fifty-years of management at Kalsow Prairie Preserve, Iowa, U.S.A. The American Midland Naturalist. 151(2): 241-250. [48494]

15. Ehrenreich, John H.; Aikman, John M. 1963. An ecological study of the effect of certain management practices on native prairie in Iowa. Ecological Monographs. 33(2): 113-130. [9]

16. Ehrenreich, John Helmuth. 1957. Management practices for maintenance of native prairie in Iowa. Ames, IA: Iowa State College. 159 p. Dissertation. [53312]

17. Fassett, Norman C. 1951. Grasses of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. 173 p. [21728]

18. Fell, Egbert W. 1957. Plants of a northern Illinois sand deposit. The American Midland Naturalist. 58(2): 441-451. [60681]

19. Frolik, A. L. 1941. Vegetation on the peat lands of Dane County, Wisconsin. Ecological Monographs. 11(1): 117-140. [16805]

20. Geier, Anthony R.; Best, Louis B. 1980. Habitat selection by small mammals of riparian communities: evaluating effects of habitat alterations. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 44(1): 16-24. [25535]

21. Gleason, Henry A.; Cronquist, Arthur. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. 2nd ed. New York: New York Botanical Garden. 910 p. [20329]

22. Goodrich, Sherel; Neese, Elizabeth. 1986. Uinta Basin flora. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Region, Ashley National Forest; Vernal, UT: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Vernal District. 320 p. [23307]

23. Graham, Liza; Knight, Richard L. 2004. Multi-scale comparisons of cliff vegetation in Colorado. Plant Ecology. 170: 223-234. [82570]

24. Great Plains Flora Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1392 p. [1603]

25. Hall, James B.; Hansen, Paul L. 1997. A preliminary riparian habitat type classification system for the Bureau of Land Management districts in southern and eastern Idaho. Tech. Bull. No. 97-11. Boise, ID: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management; Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry, Riparian and Wetland Research Program. 381 p. [28173]

26. Hallsten, Gregory P.; Skinner, Quentin D.; Beetle, Alan A. 1987. Grasses of Wyoming. 3rd ed. Research Journal 202. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, Agricultural Experiment Station. 432 p. [2906]

27. Hann, Wendel; Havlina, Doug; Shlisky, Ayn; [and others]. 2010. Interagency fire regime condition class (FRCC) guidebook, [Online]. Version 3.0. In: FRAMES (Fire Research and Management Exchange System). National Interagency Fuels, Fire & Vegetation Technology Transfer (NIFTT) (Producer). Available: http://www.fire.org. [81749]

28. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R. 1988. The vegetation of the Grand River/Cedar River, Sioux, and Ashland Districts of the Custer National Forest: a habitat type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-157. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 68 p. [771]

29. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R.; Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1984. The vegetation of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota: a habitat type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-113. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 35 p. [1077]

30. Hansen, Paul L.; Pfister, Robert D.; Boggs, Keith; Cook, Bradley J.; Joy, John; Hinckley, Dan K. 1995. Classification and management of Montana's riparian and wetland sites. Misc. Publ. No. 54. Missoula, MT: The University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station. 646 p. [24768]

31. Harrison, A. Tyrone. 1980. The Niobrara Valley Preserve: Its biogeographic importance and description of its biotic communities. Unpublished report to the Nature Conservancy. On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. 116 p. [5736]

32. Hartnett, David C. 2007. Effects of fire on vegetation dynamics in tallgrass prairie: 30 years of research at the Konza Prairie Biological Station. In: Masters, Ronald E.; Galley, Krista E. M., eds. Fire in grassland and shrubland ecosystems: Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers fire ecology conference; 2005 October 17-20; Bartlesville, OK. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 59. Abstract. [69738]

33. Higgins, Jeremy J.; Larson, Gary E.; Higgins, Kenneth F. 2001. Floristic comparisons of tallgrass prairie remnants managed by different land stewardships in eastern South Dakota. In: Bernstein, Neil P.; Ostrander, Laura J., eds. Seeds for the future; roots of the past: Proceedings of the 17th North American prairie conference; 2000 July 16-20; Mason City, IA. Mason City, IA: North Iowa Area Community College: 21-31. [46489]

34. Hirsch, Kathie Jean. 1985. Habitat classification of grasslands and shrublands of southwestern North Dakota. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University. 281 p. Dissertation. [40326]

35. Hitchcock, A. S. 1951. Manual of the grasses of the United States. 2nd edition. Misc. Publ. No. 200. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Administration. 1051 p. [Revised by Agnes Chase in two volumes. New York: Dover Publications]. [1165]

36. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 730 p. [1168]

37. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur; Ownbey, Marion. 1969. Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 1: Vascular cryptogams, gymnosperms, and monocotyledons. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 914 p. [1169]

38. Hoover, David E.; Gipson, Philip S.; Pontius, Jeffrey S.; Hynek, Alan E. 2001. Short-term effects of cattle exclusion on riparian vegetation in southeastern Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 104(3/4): 212-222. [82467]

39. Huddle, Julie A.; Tichota, Gina R.; Stubbendieck, James; Stumpf, Julie A. 2001. Evaluation of grassland restoration at Scotts Bluff National Monument. In: Bernstein, Neil P.; Ostrander, Laura J., eds. Seeds for the future; roots of the past: Proceedings of the 17th North American prairie conference; 2000 July 16-20; Mason City, IA. Mason City, IA: North Iowa Community College: 125-135. [46518]

40. Hulett, G. K.; Sloan, Clair D.; Tomanek, G. W. 1968. The vegetation of remnant grasslands in the loessial region of northwestern Kansas and southwestern Nebraska. The Southwestern Naturalist. 13(4): 377-391. [74322]

41. Isaak, Daniel; Marshall, William H.; Buell, Murray F. 1959. A record of reverse plant succession in a tamarack bog. Ecology. 40(2): 317-320. [10551]

42. Jonas, Robert J. 1966. Merriam's turkeys in southeastern Montana. Technical Bulletin No. 3. Helena, MT: Montana Fish and Game Department. 36 p. [76536]

43. Jones, Stanley D.; Wipff, Joseph K.; Montgomery, Paul M. 1997. Vascular plants of Texas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 404 p. [28762]

44. Kartesz, John T. 1999. A synonymized checklist and atlas with biological attributes for the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. 1st ed. In: Kartesz, John T.; Meacham, Christopher A. Synthesis of the North American flora (Windows Version 1.0), [CD-ROM]. Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina Botanical Garden (Producer). In cooperation with: The Nature Conservancy; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service; U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. [36715]

45. Kartesz, John Thomas. 1988. A flora of Nevada. Reno, NV: University of Nevada. 1729 p. Dissertation. [In 2 volumes]. [42426]

46. Kindscher, Kelly; Tieszen, Larry L. 1998. Floristic and soil organic matter changes after five and thirty-five years of native tallgrass prairie restoration. Restoration Ecology. 6(2): 181-196. [38831]

47. Lamson-Scribner, F. 1900. Economic grasses. Bulletin No. 14. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Agrostology. 85 p. [4282]

48. LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment. 2005. Reference condition modeling manual (Version 2.1). Cooperative Agreement 04-CA-11132543-189. Boulder, CO: The Nature Conservancy; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; U.S. Department of the Interior. 72 p. On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [66741]

49. LANDFIRE Rapid Assessment. 2007. Rapid Assessment potential natural vegetation groups (PNVGs): Associated vegetation descriptions and geographic distributions. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Lab; U.S. Geological Survey; Arlington, VA: The Nature Conservancy. 84 p. [66533]

50. Larson, Gary E. 1993. Aquatic and wetland vascular plants of the Northern Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-238. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 681 p. Available online: http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/plants/vascplnt/index.htm [2011, June 29]. [22534]

51. Lawrence, Donna L.; Romo, J. T. 1994. Tree and shrub communities of wooded draws near the Matador Research Station in southern Saskatchewan. The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 108(4): 397-412. [46867]

52. Layser, Earle F. 1980. Flora of Pend Oreille County, Washington. Pullman, WA: Washington State University, Cooperative Extension. 146 p. [1427]

53. Leary, Cathlene I.; Howes-Kieffer, Carolyn. 2004. Comparison of standing vegetation and seed bank composition one year following hardwood reforestation in southwestern Ohio. Ohio Journal of Science. 104(2): 20-28. [52854]

54. Lewis, Francis J.; Dowding, Eleanor S.; Moss, E. H. 1928. The vegetation of Alberta: II. The swamp, moor and bog forest vegetation of central Alberta. Journal of Ecology. 16: 19-70. [12798]

55. Magee, Dennis W.; Ahles, Harry E. 2007. Flora of the Northeast: A manual of the vascular flora of New England and adjacent New York. 2nd ed. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. 1214 p. [74293]

56. Maier, Chris T. 1976. An annotated list of the vascular plants of Sand Ridge State Forest, Mason County, Illinois. Transactions, Illinois State Academy of Sciences. 69(2): 153-175. [37897]

57. Marshall, William H.; Buell, Murray F. 1955. A study of the occurrence of amphibians in relation to a bog succession, Itasca State Park, Minnesota. Ecology. 36(3): 381-387. [16690]

58. Martin, William C.; Hutchins, Charles R. 1981. A flora of New Mexico. Volume 2. Germany: J. Cramer. 2589 p. [37176]

59. Muldavin, Esteban H.; DeVelice, Robert L.; Ronco, Frank, Jr. 1996. A classification of forest habitat types: southern Arizona and portions of the Colorado Plateau. RM-GTR-287. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 130 p. [27968]

60. Muldavin, Esteban; Durkin, Paula; Bradley, Mike; Stuever, Mary; Mehlhop, Patricia. 2000. Handbook of wetland vegetation communities of New Mexico. Volume 1: classification and community descriptions. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico, Biology Department; New Mexico Natural Heritage Program. 172 p. [+ appendices]. [45517]

61. Nielsen, Etlar L.; Moyle, John B. 1941. Forest invasion and succession on the basins of two catastrophically drained lakes in northern Minnesota. The American Midland Naturalist. 25(3): 564-579. [62782]

62. Nixon, E. S. 1967. A vegetational study of the Pine Ridge of northwestern Nebraska. The Southwestern Naturalist. 12(2): 134-145. [73338]

63. Peterson, Eric B. 2008. International vegetation classification alliances and associations occurring in Nevada with proposed additions. Carson City, NV: Nevada Natural Heritage Program. 347 p. Available online: http://heritage.nv.gov/sites/default/files/library/ivclist-big.pdf [2017, April 19]. [77864]

64. Pohl, Richard W. 1969. Muhlenbergia, subgenus Muhlenbergia (Gramineae) in North America. The American Midland Naturalist. 82(2): 512-542. [83283]

65. Pohl, Richard W.; Mitchell, William W. 1965. Cytogeography of the rhizomatous American species of Muhlenbergia. Brittonia. 17(2): 107-112. [82593]

66. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

67. Rosburg, Thomas R.; Jurik, Thomas W.; Glenn-Lewin, David C. 1994. Seed banks of communities in the Iowa Loess Hills: ecology and potential contribution to restoration of native grassland. In: Wickett, Robert G.; Lewis, Patricia Dolan; Woodliffe, Allen; Pratt, Paul, eds. Spirit of the land, our prairie legacy: Proceedings, 13th North American prairie conference; 1992 August 6-9; Windsor, ON. Windsor, ON: Department of Parks and Recreation: 221-237. [24697]

68. Rydberg, P. A. 1915. Phytogeographical notes on the Rocky Mountain region. V. Grasslands of the subalpine and montane zones. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 42(11): 629-642. [60596]

69. Schmutz, Ervin M.; Dennis, Arthur E.; Harlan, Annita; Hendricks, David; Zauderer, Jeffrey. 1976. An ecological survey of Wide Rock Butte in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science. 11(3): 114-125. [75978]

70. Schott, Gary W.; Hamburg, Steven P. 1997. The seed rain and seed bank of an adjacent native tallgrass prairie and old field. Canadian Journal of Botany. 75(1): 1-7. [27399]

71. Scoggan, H. J. 1978. The flora of Canada. Part 2: Pteridophyta, Gymnospermae, Monocotyledoneae. National Museum of Natural Sciences: Publications in Botany, No. 7(2). Ottawa, ON: National Museums of Canada. 545 p. [75494]

72. Seymour, Frank Conkling. 1982. The flora of New England. 2nd ed. Phytologia Memoirs 5. Plainfield, NJ: Harold N. Moldenke and Alma L. Moldenke. 611 p. [7604]

73. Stevens, O. A. 1921. Plants of Fargo, North Dakota, with dates of flowering. The American Midland Naturalist. 7(4/5): 135-156. [63630]

74. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species comprising secondary plant succession in northern Rocky Mountain forests. FEIS workshop: Postfire regeneration. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. 10 p. [20090]

75. Stubbendieck, J.; Nichols, James T.; Roberts, Kelly K. 1985. Nebraska range and pasture grasses (including grass-like plants). E.C. 85-170. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, Department of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service. 75 p. [2269]

76. Stubbendieck, James; Coffin, Mitchell J.; Landholt, L. M. 2003. Weeds of the Great Plains. 3rd ed. Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Plant Industry. 605 p. In cooperation with: University of Nebraska, Lincoln. [50776]

77. Stubbendieck, James; Hatch, Stephan L.; Butterfield, Charles H. 1992. North American range plants. 4th ed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. 493 p. [25162]

78. Szaro, Robert C. 1989. Riparian forest and scrubland community types of Arizona and New Mexico. Desert Plants. 9(3-4): 70-138. [604]

79. Tester, John R. 1996. Effects of fire frequency on plant species in oak savanna in east-central Minnesota. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 123(4): 304-308. [28035]

80. Travnicek, Andrea J.; Lym, Rodney G.; Prosser, Chad. 2005. Fall-prescribed burn and spring-applied herbicide effects on Canada thistle control and soil seedbank, in a northern mixed-grass prairie. Rangeland Ecology & Management. 58(4): 413-422. [55528]

81. Uresk, Daniel W.; Paintner, Wayne W. 1985. Cattle diets in a ponderosa pine forest in the northern Black Hills. Journal of Range Management. 38(5): 440-442. [2401]

82. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2017. PLANTS Database, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

83. Vestal, Arthur G. 1917. Foothills vegetation in the Colorado Front Range. Botanical Gazette. 64(5): 353-385. [64489]

84. Vogl, R. J. 1964. The effects of fire on the vegetational composition of bracken-grassland. Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. 53: 67-82. [9142]

85. Vogl, Richard John. 1961. The effects of fire on some upland vegetation types. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. 154 p. Dissertation. [52282]

86. Voss, Edward G. 1972. Michigan flora. Part I: Gymnosperms and monocots. Bulletin 55. Bloomfield Hills, MI: Cranbrook Institute of Science; Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Herbarium. 488 p. [11471]

87. Wali, M. K.; Killingbeck, K. T.; Bares, R. H.; Shubert, L. E. 1980. Vegetation-environment relationships of woodland and shrub communities, and soil algae in western North Dakota. North Dakota Regional Environmental Assessment Program (REAP): ND REAP Project No. 7-01-1. Grand Forks, ND: University of North Dakota, Department of Biology. 159 p. [7433]

88. Weber, William A. 1987. Colorado flora: western slope. Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press. 530 p. [7706]

89. Weber, William A.; Wittmann, Ronald C. 1996. Colorado flora: Eastern slope. 2nd ed. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. 524 p. [27572]

90. Welsh, Stanley L.; Atwood, N. Duane; Goodrich, Sherel; Higgins, Larry C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. The Great Basin Naturalist Memoir No. 9. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University. 894 p. [2944]

91. White, Jon A.; Glenn-Lewin, David C. 1984. Regional and local variation in tallgrass prairie remnants of Iowa and eastern Nebraska. Vegetatio. 57(2/3): 65-78. [82466]

92. Wilson, Roger E. 1970. Succession in stands of Populus deltoides along the Missouri River in southeastern South Dakota. The American Midland Naturalist. 83(2): 330-342. [25441]