Medicinal Botany

Our earliest human ancestors found plants to heal wounds, cure diseases, and ease troubled minds. People on all continents have long used hundreds, if not thousands, of indigenous plants, for treatment of various ailments dating back to prehistory. Knowledge about the healing properties or poisonous effects of plants, mineral salts, and herbs accumulated from these earliest times to provide health and predates all other medical treatment.

How long have people been using medicinal plants?

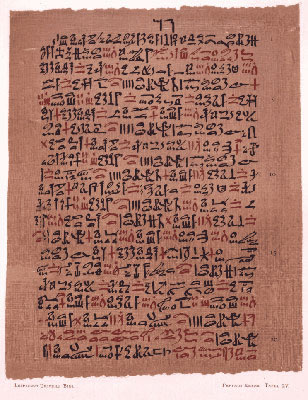

In 3500 BC, Ancient Egyptians began to associate less magic with the treatment of disease, and by 2700 BC the Chinese had started to use herbs in a more scientific sense. Egyptians recorded their knowledge of illnesses and cures on temple walls and in the Ebers papyrus (1550 BC), which contains over 700 medicinal formulas.

Hippocrates, 460-380 BC, known as the “Father of Medicine,” classified herbs into their essential qualities of hot and cold, moist and dry, and developed a system of diagnosis and prognosis using herbs. The number of effective medicinal plants he discussed was between 300 and 400 species.

Aristotle, the philosopher, also compiled a list of medicinal plants. His best student, Theophrastus discussed herbs as medicines, the kinds and parts of plants used, collection methods, and effects on humans and animals. He started the science of botany with detailed descriptions of medicinal plants growing in the botanical gardens in Athens.

The most significant contribution to the medicinal plant descriptions was made by Dioscorides. While serving as a Roman army physician, he wrote De Materia Medica in about AD 60. This five-volume work is a compilation concerning approximately 500 plants and describes the preparation of about 1000 simple drugs. Written in Greek, it contains good descriptions of plants giving their origins and medical virtues and remained the standard text for 1,500 years.

The earliest Ayurvedic texts on medicine from India date from about 2,500 BC. In Ayurvedic theory, illness is seen in terms of imbalance, with herbs and dietary controls used to restore equilibrium. Abdullah Ben Ahmad Al Bitar (1021–1080 AD) an Arabic botanist and pharmaceutical scientist, wrote the Explanation of Dioscorides Book on Herbs. Later, his book, The Glossary of Drugs and Food Vocabulary, contained the names of 1,400 drugs. The drugs were listed by name in alphabetical order in Arabic, Greek, Persian or Spanish.

Galen, a physician considered the “medical pope” of the Middle Ages, wrote extensitvely about the body’s four “humors” — the four fluids that were thought to permeate the body and influence its health. Drugs developed by Galen were made from herbs that he collected from all over the world.

The studies of botany and medicine became very closely linked during the Middle Ages. Virtually all reading and writing were carried out in monasteries. Monks laboriously copied and compiled the manuscripts. Following the format of Greek botanical compilations, the monks prepared herbals that described identification and preparation of plants with reported medicinal characteristics. At this time though, healing was as much a matter of prayer as medicine. Early herbalists frequently combined religious incantations with herbal remedies believing that with “God’s help” the patient would be cured.

With time, pracitioners began to focus on healing skills and medicines. By the 1530s, Paracelsus (born Philippus Theophrasts Bombastus von Hohenheim, near Zurich in 1493), was changing Europes attitudes toward health care. Many physicians and apothecaries were dishonest and took advantage from those they should be helping. Paracelsus was a physician and alchemist who believed that medicine should be simple and straight forward. He was greatly inspired by the Doctrine of Signatures, which maintained that the outward appearance of a plant gave an indication of the problems it would cure. This theory is sometimes surprisingly acurate.

In 1775, Dr. William Withering was treating a patient with severe dropsy caused by heart failure. He was unable to bring about any improvement with traditional medicines. The patient’s family administered an herbal brew based on an old family recipe and the patient started to recover. Dr. Withering experimented with the herbs contained in the recipe and identified foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) as the most significant. In 1785, he published his Account of the Foxglove and Some of Its Medical Uses. He detailed 200 cases where foxglove had successfully been used to treat dropsy and heart failure along with his research on the parts of the plant and harvest dates that produced the strongest effect. Withering also realized that theraputic dose of foxglove is very close to the toxic level where side effects develop. After further analysis, the cardiac glycosides digoxin and digitoxin were eventually extracted. These are still used in treating heart conditions today.

In 1803, morphine became one of the first drugs to be isolated from a plant. It was identified by Frederich Serturner in Germany. He was able to extract white crystal from crude opium poppy. Scientists soon used similar techniques to produce aconitine from monkshood, emetine from ipecacuanha, atropine from deadly nightshade, and quinine from Peruvian bark.

In 1852, scientists were able to synthesize salicin, an active ingredient in willow bark, for the first time. By 1899, the drug company Bayer, modified salicin into a milder form of aectylsalicylic acid and lauched asprin into our modern world.

The synthetic age was born and in the following 100 years, plant extracts have filled pharmacy shelves. Although many medicines have been produced from plant extracts, chemists sometimes find that the synthetic versions do not carry the same therapeutic effects or may have negative side effects not found when using the whole plant source.

A full 40 percent of the drugs behind the pharmacist’s counter in the Western world are derived from plants that people have used for centuries, including the top 20 best selling prescription drugs in the United States today. For example, quinine extracted from the bark of the South American cinchona tree (Cinchona calisaya) relieves malaria, and licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) has been an ingredient in cough drops for more than 3,500 years. The species native to the United States, Glycyrrhiza lepidota, has a broad range from western Ontario to Washington, south to Texas, Mexico and Missouri. Eastward, there are scattered populations. The leaves and roots have been used for treating sores on the backs of horses, toothaches, and fever in children, sore throats and cough.

Medicinal interest in mints dates from at least the first century A.D., when it was recorded by the Roman naturalist Pliny. In Elizabethan times more than 40 ailments were reported to be remedied by mints. The foremost use of mints today in both home remedies and in pharmaceutical preparations is to relieve the stomach and intestinal gas that is often caused by certain foods.

Consumers routinely assume that the medications they take and the food they ingest have been scrupulously studied by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They assume that many of these products are safe because they are natural. However, many herbals have never been seriously tested for efficacy or toxicity. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 eliminated the authority of the FDA to regulate vitamins, herbs and other food-based products, and therefore the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not regulate the use of any herbal supplement.

How Plants Protect Us

Strawberries and other familiar fruits—and some vegetables—contain natural phytochemicals that can destroy leukemia cells.

Strawberries and other familiar fruits—and some vegetables—contain natural phytochemicals that can destroy leukemia cells.

Susan J. Zunino, an Agricultural Research Service molecular biologist, leads the nutrition-focused research investigating the health-imparting effects of plant chemicals, or phytochemicals, using laboratory cultures of both healthy human blood cells and cancerous ones as her models. Zunino's pioneering studies reveal the previously unknown ability of about a half-dozen phytochemicals to stop growth of this type of leukemia. The findings are of interest to cancer researchers and to nutrition researchers exploring the health benefits of compounds in the world's edible fruits, vegetables, herbs, and spices.

De Materia Medica.

De Materia Medica.

Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea). Photo by Tom Heutte, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea). Photo by Tom Heutte, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum). Illustration by Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany.

Opium poppy (Papaver somniferum). Illustration by Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz 1885, Gera, Germany.

South American cinchona tree or quinine (Cinchona calisaya). Illustration by Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897.

South American cinchona tree or quinine (Cinchona calisaya). Illustration by Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897.

Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza lepidota). Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org.

Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza lepidota). Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org.