A hotly anticipated cicada double brood is expected to emerge across much of the eastern United States from late April through May this year. It’s been over two centuries since these two broods last emerged in the same year, back in 1803.

These cicadas belong to “periodical” broods, which remain underground as nymphs until they emerge en masse and shed their exoskeletons in a 13- or 17-year cycle. Once aboveground, these noisy 1- to 2-inch flying insects are hard to miss, but they live for just a few weeks to buzz, feed and breed.

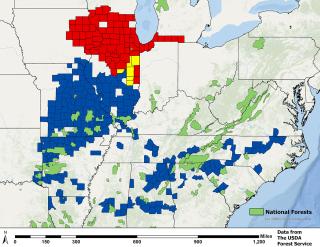

This year will see the emergence of Brood XIII, a 17-year brood in northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, northwestern Indiana, southwestern Michigan and eastern Iowa, and Brood XIX, a 13-year brood concentrated in southern Illinois and much of Missouri and scattered across southeastern states stretching to Virginia. Some areas in central Illinois could see overlap of both broods.

Literally trillions of the insects will gradually emerge and begin their daily raucous chorus, for the joy of some people and annoyance of others. So many cicadas will make their noise at once in some places that sound levels might reach upward of 90 to 120 decibels, equivalent to a gas-powered lawnmower or motorcycle.

But at least the cicadas observe quiet hours. Unlike some other insect species, cicadas “sing” during the day, producing their sound by expanding and contracting a membrane called a tymbal. And be grateful that only male cicadas sing, in their efforts to attract females for mating.

Periodical cicadas typically begin to emerge when the soil temperature reaches roughly 64°F, expected from April to early May in the more southern area of their range and from May to early June in their more northern locations.

Though often grouped together when discussed, broods are not a single species. Brood XIII, which emerges on a 17-year cycle, is comprised of three species: Magicicada cassini, M. septendecim and M. septendecula. Brood XIX, which is on a 13- year cycle, is comprised of four species, M. neotredecim, M. tredecim, M. tredecassini and M. tredecula.

The sight and sound of so many cicadas may be overwhelming, but luckily these insects can’t significantly harm humans or pets. This is because “they have no ‘biting’ mouth parts,” according to Stephen Burr, the USDA Forest Service Eastern Region’s Forest Health Monitoring coordinator.

What cicadas do have is “a piercing-sucking mouthpart called a rostrum,” Burr said. To eat, the cicadas insert their rostrum into plant stems when above ground and roots below ground and feed on plant xylem.

But if you hold a cicada, Burr said, “it may attempt to feed and can penetrate the skin, which will hurt.” Still, he advised not to take it personally, adding, “This is not a defense act; they have mistaken you for a tree, but this is unlikely.”

However, cicadas can harm plants and some varieties of trees. “When females oviposit, or lay eggs,” Burr said, “they create slits in branches, which can weaken branches, causing leaves to die and stems to break.” When leaves turn color as they die, this cicada damage is called “flagging.”

Cicadas could cause damage to a variety of hardwood trees, including forest, shade and fruit trees such as oak, hickory, apple, birch or dogwood.

How much damage cicadas do depends on a tree’s size and age. Large trees may have multiple branch tips destroyed but will survive, while small trees can be killed by ovipositing females. This can be prevented by covering high-value young trees with netting prior to emergence, Burr said.

The Forest Service will track the damage from cicadas, as they do with other damage-causing agents, and provide information to resource managers, landowners and the public.

Just how many cicadas are there? Currently, there are 12 recognized 17-year broods and three 13-year broods. Studies on cicada populations vary, but Burr noted that some studies estimate over a million cicadas per acre.

For the emerging broods, there is safety in numbers. Individually, cicadas are vulnerable to the many creatures that feed on them: “Insects and other arthropods, birds, fish, lizards, mammals, even people,” Burr said. “Just about everything. Mass emergence is a defense mechanism. There are so many out at one time predators can’t kill them all and large numbers successfully reproduce.”

For anyone seeing a brood emerge for the first time, it is a novel experience. But cicadas are far from new on this landscape. “They have been on this continent longer than humans,” Burr said.