Animals

Fish and wildlife are managed across the forest and in partnership with Colorado Parks and Wildlife and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure diverse and sustainable populations.

The wildlife and fisheries staff of the Rio Grande National Forest manages animal and plant habitats within the National Forest system and provides guidance for interdisciplinary projects such as timber, recreation, and fuels treatments. The intent is to ensure diverse and sustainable populations of native plants and animals.

The Forest provides habitat for many species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Many federally recognized as threatened or endangered animal species, including Canada lynx, southwestern willow flycatcher, Uncompahgre fritillary butterfly, and yellow-billed cuckoo call the Forest home. The Forest represents a large part of the core habitat for Canada lynx within Colorado. Canada lynx were reintroduced into the state from 1999 to 2006. The Forest also provides for great public fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching. Big game species include Rocky Mountain elk, Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, moose, mule deer, and pronghorn are plentiful. Hundreds of miles of streams and rivers along with multiple lakes provide fishing opportunities for a variety of trout species, including the native Rio Grande cutthroat trout.

Threatened and endangered species on the Forest include: Canada lynx, gray wolf, New Mexico meadow jumping mouse, Gunnison sage-grouse, Mexican spotted owl, southwestern willow flycatcher, yellow-billed cuckoo, Bonytail, monarch butterfly, silverspot butterfly, Suckley’s cuckoo bumble bee, and Uncompahgre fritillary butterfly.

Fish and wildlife biologists work to improve habitat for all fish and wildlife species through habitat restoration projects. Other primary duties include providing input to other resource projects on the forest like recreation, vegetation and fuels management during the NEPA process. The intent is to ensure diverse and sustainable populations of native plants and animals. Fishing and hunting opportunities are managed primarily by Colorado Parks and Wildlife, with assistance from Forest staff on population monitoring, status and trend data collection.

Species on the Forest

Golden Mantled Ground Squirrels are a common sight on the forest.

Photo Credit: Rio Grande National ForestGround Squirrels

Golden mantle ground squirrel

There are many little critters you may see while visiting the Forest. Golden mantled ground squirrels, Colorado chipmunks, and least chipmunks frequent campsites. Golden mantled ground squirrels can be differentiated from the chipmunks because they are a little bigger and do not have stripes on their face. Chipmunks have stripes on their body and their face. Remember, do not feed wildlife as human food can make them sick and wildlife may carry diseases.

Gunnison's prairie dog

Gunnison's prairie dog is a type of ground squirrel that also lives on the forest. The Gunnison's prairie dog is a species of concern on the forest and was petitioned to be added to the endangered or threatened species list however it was not added. Populations are being monitored.

Ungulates

The Forest is also home to many larger mammals, including five species of ungulates, (hoofed animals). The ungulates of the forest are often referred to as big game. Be careful when driving on roads in and around the forest as you will likely see some of these species along the roadway. Deer and elk roam across the Forest from high elevations in the summer to lower areas in winter. Not all deer and elk migrate up and down in elevation with the changes of the season, but many herds do. Elk are bigger than deer and have a white rump and a more bearded neck. Mule deer are the species of deer most common across the forest.

Elk calf stays put while its mother is away.

Photo Credit: Doug Clark, Rio Grande National ForestBighorn sheep prefer steeper, rockier terrain. They are great mountain climbers. Bighorn sheep rams (males) grow large curly horns and the ewes (females) have smaller horns that don’t curl. There are a few populations of bighorn sheep across the forest. Moose also live on the forest, and they prefer willowed and wetter areas. They are the largest member of the deer family. Moose are not native to Colorado, they were introduced to Colorado in 1978 with individuals from Utah and Wyoming. Later they were introduced to the Rio Grande National Forest area in 1991-1993.

The Pronghorn is the fastest land mammal in North America and can run at speeds of 55 mph. They prefer to live in the lower elevations and open areas where they can use their speed. They are often called antelope and while they resemble antelope, they are not closely related to the antelope that live in Africa. The pronghorn’s closest living relative is actually a giraffe!

Horns or Antlers?

Antlers are made of bone and grown right from the skull. Members of the deer family have antlers and are usually found on the males. Antlers are shed annually and are re grown each year. When antlers are growing they are covered in ‘velvet’ a thin, soft layer of skin and blood vessels. This ‘velvet’ is then shed and later the antlers. Antlers grow in a branching pattern where horns don’t.

Horns are found on animals like bighorn sheep, bison, cows, and goats. The horn is made of an interior portion that is bone and an outer sheath that is made of keratin, the same material as our fingernails. Horns are often found on both males and females although the horns are usually smaller on females like in the case of bighorn sheep. Horns are never shed and grow continually throughout the animal’s life.

Pronghorn are unique in that they have a horn that has core of bone and a sheath of keratin. The structure of a pronghorn’s horn is like a horn, but the other characteristics are much more similar to antlers, an interesting mix! The keratin sheath is branched, and this sheath is shed each year, unlike horns and more similar to antlers.

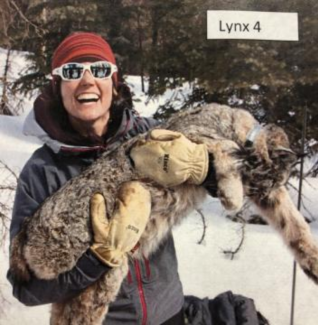

Lynx: Return of the Snow Cats

The Rio Grande National Forest played a key role in Lynx reintroduction.

Photo Credit: Rio Grande National ForestLynx reintroduction

Lynx are a wild cat that loves to live in cold, snowy areas like our mountains here in Colorado. They have big paws to help them walk on top of snow, like snowshoes! They are bigger than the more common bobcat and have ear tufts and a tail with a black tip rather than spotted like the bobcat.

Historically Lynx were trapped for fur and the lynx population in Colorado dropped rapidly through the late 1800s and early 1900s. Colorado state listed lynx as an endangered species in 1973 and the last known lynx in Colorado was illegally trapped in 1974. Lynx also faced habitat fragmentation which further impacted their population numbers.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) worked to bring back lynx to the state through a reintroduction program. In 1999 the first lynx were brought from Canada and Alaska to the San Juan Mountains. Over several years over 200 individuals were brought to Colorado to create a self-sustaining population. Today lynx are rare, but their reintroduction was a success.

American Beavers

Beavers are famous for their engineering skills, as they can quickly construct exceptionally sturdy dams and lodges using the materials found naturally in their environment. They are so good at their jobs that they create entire new ecosystems that benefit many other species. By damming the river and flooding an area, beavers create wetland environments that provide lush vegetation on which other herbivores feed. The aquatic life that thrives in these calm waters also attracts all manner of waterfowl who favor beaver ponds as feeding and nesting grounds. The lush vegetation also provides habitat for extensive insect diversity, which a plethora of insectivorous birds capitalize on. Trout species utilize the deep pools and aquatic insects that thrive in beaver dams.

Deployment of an autonomous recording unit at the Antora Meadows bat monitoring site located within the Saguache Ranger District.

Photo Credit: Brandon Skerbetz, Rio Grande National Forest- The Rio Grande National Forest, in partnership with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and Frisco Creek Rehabilitation Center, work each year to translocate beaver. This approach mitigates conflicts with beavers on private property by relocating them onto the Forest where their ecosystem services can provide significant benefits to the broader environment.

- Beavers are a focal species for the Rio Grande National Forest and are tied to multiple Forest Plan monitoring questions. These questions serve as a tool to review the effectiveness of management actions on the Forest. Monitoring questions related to beaver help to ascertain water ecosystem health and riparian ecosystem health.

Bats

There are 20 species of bats known to live in Colorado, with 14 of these species occurring on the Forest; some are here year-round, and some only migrate through the state. Though commonly misunderstood, bats actually play a valuable role in ecosystems across Colorado. Bats can be found in every habitat on the Forest, from the lower elevation plains to the high mountain forests. All of our bats eat insects and help control our insect populations. The Little brown bat has been known to catch and eat up to 4,500 insects, including mosquitoes, every night! The Rio Grande National Forest continually monitors bat populations as part of a nationwide effort to detect changes from challenges including white-nose syndrome, climate change, energy and land use development.

A white tailed Ptarmigan blends in with it's surroundings.

Photo Credit: Rio Grande National ForestAt night, listen for owls. At lower elevations in ponderosa or Douglas fir stands you may hear a flammulated owl who has a very low hoot for a tiny owl. Flammulated owls primary eat insects, especially crickets, moths, and beetles. At higher elevations in spruce-fir forests you may hear a boreal owl. Like most owls, the boreal owl hunts rodents and other small mammals primarily at night.

Change Artists

At high elevations above the trees, you might spot a well camouflaged white-tailed ptarmigan. These birds change color to camouflage with the seasons, turning white in winter and greyish brown in the summer.

Olive sided fly catchers like forests with many open areas that make hunting insects easier. Often, they will inhabit previously burned areas. You may be more likely to hear this bird as it has a recognizable whistling call that sounds much like quick, three beers!

Common birds you may see around camp include juncos, hermit thrushes, and several species of corvids (crow family), including Canada jays, Steller's jays, and Clark’s nutcrackers. Other common birds include: American robin, ruby-crowned kinglet, song sparrow, broad-tailed hummingbird, mountain chickadee, evening grosbeak, black-headed grosbeak, Cassin’s finch, house finch, common raven, dusky grouse, mountain bluebird, northern flicker, red-naped sapsucker, hairy woodpecker, western tanager, yellow-rumped warbler, American kestrel, great horned owl, Townsend’s solitaire, bushtit, all 3 species of nuthatch (white-breasted, red-breasted, and pygmy), and horned lark.

You can report bird sightings on the iNaturalist app. The Merlin Bird ID app is a great tool to help identify and track your sightings too. Use eBird for tracking bird observations.

A Boreal Toad with a thin white stripe down its back blends in with his muddy surroundings.

Amphibians inhabit the wetter meadows, ponds, and forests. Chorus frogs and barred tiger salamanders are found throughout the Forest.

Boreal Toad

The boreal toad is rare and listed as an endangered species in Colorado. Many partners including CPW and the USFS are working to monitor and improve habitat for boreal toads on the Forest and across the state.

The largest known threat to boreal toads is exposure to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, better known as chytrid fungus. Exposure to this fungus causes a severe skin disease that is easily spread and can cause death to whole populations. Properly disinfecting equipment, clothing, and footwear between bodies of water is an effective conservation measure that humans can take to help protect boreal toad populations in Colorado.

The western Bumble Bee.

Our biologists are monitoring two rare insects on the Forest. At high elevations, the white veined arctic butterfly is a rare find across the Forest. The western bumblebee is also of interest but since there are many different bee species, all of which are important pollinators, they can be very difficult to tell apart!

Western bumblebee

Although the western Bumble Bee is at fairly low risk of extinction it is still Colorado State and USDA Forest Services’ greatest need for Conservation.

As of June 2015, this species has recently become a sensitive Species for USFS Region 2, and it is fundamental to spread awareness.

Threats and risk factors

Their decline across the western U.S. appears to be related to a wide variety of factors, specifically these include major habitat loss which includes agricultural and urban development, habitat fragmentation and livestock grazing. As pollinators the removal of their flowering food sources and potential nesting sites has led to the results in a decrease in genetic diversity.

Management considerations

As part of their recovery, conservation, and viability it is important to protect known and potential habitat sites and encourage nectar & pollen sources throughout their colony season and Hibernacula.

Partnerships

Bumble Bee Atlas is a community of citizens, state and federal biologists working together in collecting data through “Community Science” using surveys that would help contribute towards the better understanding of bumble bees and their needs.

A white-veined artic butterfly blends into its surroundings.

Photo Credit: Rio Grande National ForestWhite-veined artic butterfly

Over the past 20 years there has been one major known observed occurrence of this species since 1996 along with its Planning Area. Since this species only lay eggs every other year, preferably near wet tundra and alpine bog habitats. There their eggs will feed, grow, and hibernate on the sedge for two years until maturity. This species can survive this far south due to geological high-altitude tundra areas.

Threats & Risk Factors

Like many other species that live in tundra areas, climate change is their greatest threat due to loss of alpine tundra habitats in which they rely on monocot species such as grasses and sedges.

Management Considerations

This species is still under consideration to be listed as a SCC in the Rio Grande National Forest, so is their aid and monitoring objectives.

Partnerships

North American butterfly Association is also being concluded since it also based on nation citizen science in which collected project data is shared onto their annual Butterfly Count Report.

The Rio Grande Cutthroat trout and their distinctive red coloring.

The Rio Grande cutthroat trout is one of 14 species of cutthroat throughout the West but is the only native trout found on the Forest. The trout lives the furthest south of any cutthroat trout species. The Rio Grande cutthroat trout may be found in the Rio Grande and Pecos River drainages. Like many trout, they like to live at high elevations in cold, clear steams and occasionally can be found in lakes.

Learn more about the Rio Grande Cutthroat trout in the video below, listed under the “Forest Specialist Video Series” tab

The Rio Grande Sucker

Photo Credit: Tom Kennedy via iNaturalist.The Rio Grande sucker is the only native sucker found on the forest. The Rio Grande sucker is particularly vulnerable to reduced stream flows and increased sediment loads, such as soil run-off after a fire. The Rio Grande sucker suffers from predation of non-native predators, such as northern pike and brown trout, as well as resource competition with the white sucker. It can be found in slow-moving systems in lower elevations within the forest.

The Rio Grande Chub

Photo Credit: bgmooaz123 on iNaturalistThe Rio Grande chub can be found in the Rio Grande, the Pecos, and the Canadian River drainages. While considered a stable population in New Mexico, the Rio Grande Chub is a species of conservation concern within our forest. The Rio Grande chub is threatened by non-native northern pike, brown trout, and brook trout via predation and competes for habitat and food resources with the white suckers and common carp.

Beaver dam analogs

The Rio Grande National Forest is working with Colorado Parks and Wildlife to improve habitat conditions for the native trout. This includes reducing populations of non-native species that compete for food and space and creating better habitats with the help of beavers! Learn more about the trout in the video below.

A beaver dam analogue simulates a natural dam.