Looking out over the La Garita Wilderness Area in Southwest Colorado one would be hard-pressed to imagine that destructive forces at unimaginable scales are responsible for the beauty we see today. The aptly named La Garita, or Spanish for “the lookout,” is better known for its spectacular vistas, not its volcanic past.

The wilderness area lies within the San Juan Mountains, straddling both the Gunnison and Rio Grande national forests in Colorado.

Geologists have long known that the San Juan Mountains and surrounding areas were created by volcanic eruptions that began roughly 35 million years ago during the geologic period called the Eocene Epoch. The area, about the size of Vermont, was home to hundreds of volcanoes, some rising more than two miles above the surrounding landscape.

Today, the La Garita Mountains, a range within the San Juan Mountains, feature spectacular cliffs and 10 mountain peaks higher than 13,000 feet. Evidence of past volcanic activity includes columns of basalt, a type of rock that forms when lava cools quickly. Some of these columns are hundreds of feet high and are found near the top of the tallest mountains in the area.

But where are the volcanoes?

Geologists working in the 1970s identified up to 18 calderas – large, collapsed depressions marking the sites of former ancient volcanoes – in an area now named the San Juan volcanic field.

Twenty years after he helped map the area, Peter Lipman of the U.S. Geological Survey, returned to further explore the geologic history of this fire-forged landscape. What he discovered seemed straight from Greek mythology: an event so catastrophic that not even Vulcan, the god of fire and volcanoes, could have set it in motion.

Volcanoes are absent from today’s landscape because a “supervolcano” destroyed them. The eruption, 10,000 times more violent than Mount St. Helens and possibly the largest single eruption in history, produced enough lava and ash to fill Lake Michigan. This explosion left behind the La Garita Caldera, a gaping hole twice the size of Los Angeles, as the supervolcano emptied and collapsed into itself. Remnants of the volcanoes that remained were either obliterated during the eruption or were covered with ash more than 4,000 feet deep in places.

Where is all that material now?

Over time wind, water, and other forces have eroded, or worn away, the rocks that formed from the eruption. Adventurers can see this process continuing today at the spectacular Wheeler Geologic Area.

Constantly evolving, this otherworldly landscape is the result of millions of years of erosion of solidified volcanic ash layers that geologists refer to as tuff. Wheeler is host to at least four different tuffs representing separate eruptions that had slightly different chemical compositions. This gives the tuffs different colors and causes them to erode in a different way.

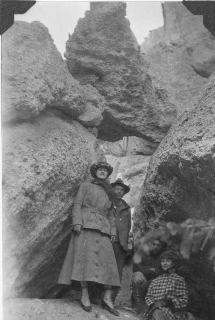

In some areas, the tuff appears to be melting into the ground while other areas feature hoodoos, columns, or pinnacles of weathered rock. Some hoodoos are needle-like while others could be mistaken for giant toadstools under a full moon. Still, others resemble tombstones, possibly a reminder of explorer John C. Fremont’s ill-fated expedition in 1849. Snowed in nearby, the expedition lost 10 men before he was rescued in January 1849. It is said that four-foot-tall stumps of trees the men cut for firewood remain in the area, an indication of how deep the snow was that winter.

Declared the first national monument in Colorado by President Roosevelt in 1908, the area experienced its heyday of visitation in a time when travelling slowly over poor roads was the norm. With the advent and rise in popularity of the automobile, tourists turned their attention to new destinations accessible by car.

As visitation plummeted, the monument was abolished. Today, this little-known geologic gem is managed by the Forest Service as part of the La Garita Wilderness. Near the old mining town of Creede, Colorado, Wheeler is accessible by a seven-mile hike or a grueling 14-mile four-wheel-drive road, which is outside of the wilderness area and allows for motorized vehicles. While doable in a day, Wheeler is best experienced at sunrise, sunset, or on a moonlit night.

To learn more about Wheeler and other unique geologic features in our national forests, visit Stories in Stone, an interactive story map created by the Forest Service’s Geologic Resources Program.