History of Mt. Hood National Forest

Since time immemorial, Mt. Hood National Forest system lands have been the home of Indigenous peoples including the Clackamas Chinook, Cascade Chinook, Wasco, Warm Springs, Tenino, and Molalla people. For thousands of years, these groups and their ancestors lived, hunted, gathered, and maintained extensive trade networks throughout the Forest. The land provided and continues to provide Tribal communities to this day with water, fish, wildlife, traditional medicines, basketry materials, berries, and roots, as well as cultural and spiritual practice areas.

From the early 1740s through the nineteenth century, native communities in the region were significantly impacted by the arrival of Euro-American populations. Due to the influx of immigrants, native communities were displaced from their ancestral lands, decimated by disease, and severed from their traditional customs, foods, and lifeways. Modern Historian Robert Boyd estimates that 45% of the native population east of the Cascades was lost to disease prior to 1805, at which time explorers Merriweather Lewis and William Clark estimated the total population of the area at 13,000.1 Between 1840 and 1860, more than 50,000 Euro-American emigrants traveled the Oregon trail to settle land in Oregon.2 The final overland segment of the Oregon Trail, the Barlow Road, runs across the Forest.

In the 1850s, the United States entered several treaties with Tribal nations, in which Tribes ceded portions of their ancestral lands in exchange for certain rights and/or land reservations. Today, many of the descendants of the native communities that once lived on Mt. Hood National Forest lands are members of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon (CTGR), the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (CTSI) and the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon (CTWS). Visit our Tribal Relations page to learn more about how the Forest works with local Tribal governments to manage the land.

In 1792, British Lieutenant William Broughton named the mountain Mt. Hood after a famous naval officer Alexander Arthur Hood. Native communities have various names in their ancestral languages for what is now known as Mt. Hood. There are as many names for the mountain as there were languages and dialects spoken in the region.

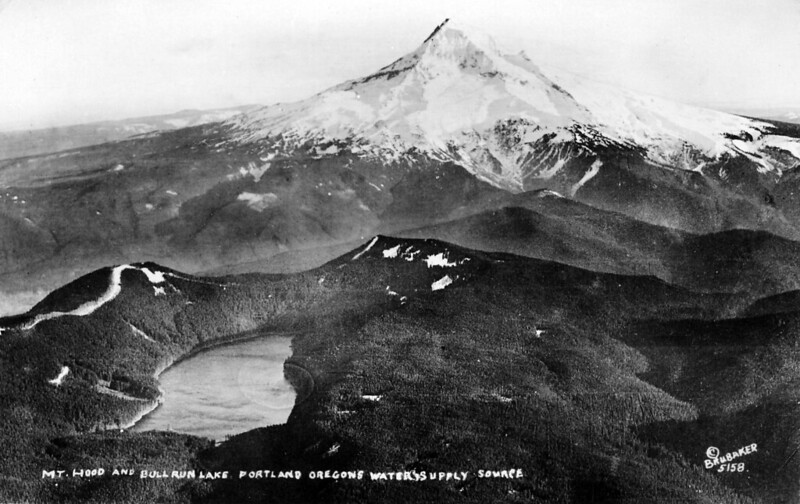

Oregon gained statehood in 1859. In 1860, the City of Portland had a population of 2,860. By 1890, the population had grown to 46,385. In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison designated the Bull Run Forest Reserve to protect the drinking water for the City of Portland, one year after the passage of the Forest Reserve Act. In 1893, he designated the Cascade Forest Reserve, which connected to the Bull Run Reserve and ran the full length of the Cascade crest nearly to the southern border of the state. In 1905, management of the Forest Reserves was moved from the Department of the Interior to the newly created Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture. At that time, the Reserves were renamed National Forests. The Oregon National Forest was created from the Cascade Forest Reserve and later renamed the Mt. Hood National Forest in 1924. The shift from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture signaled the agency’s multiple-use mission, which focuses on balancing natural resource conservation and use.

Early management of the Forest by Forest Rangers focused on patrolling for fire, illegal mining, grazing, or homesteading. To patrol and control fire, the agency began to create networks of roads, trails, guard stations, and fire lookouts. In the 1940s, there were dozens lookouts on the Forest. Today only six remain, many demolished intentionally or otherwise destroyed. In the early twentieth century, the Forest began initiating timber harvest, as well as timber permitting, mineral, and other natural resource harvest for the public.

Early management of the Forest by Forest Rangers focused on patrolling for fire, illegal mining, grazing, or homesteading. To patrol and control fire, the agency began to create networks of roads, trails, guard stations, and fire lookouts. In the 1940s, there were dozens lookouts on the Forest. Today only six remain, many demolished intentionally or otherwise destroyed. In the early twentieth century, the Forest began initiating timber harvest, as well as timber permitting, mineral, and other natural resource harvest for the public.

The first formal campground on Forest Service land in the country was built in 1916, at the time in the Oregon National Forest, at Eagle Creek, though it looked much different than campgrounds today, with one large parking lot and adjacent camping area. Today, Eagle Creek campground is part of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. By the 1920s, recreation popularity was growing in the National Forests, and the agency began to create formal campgrounds, hiking trails, and picnic areas.

During World War II, Mt. Hood National Forest had to shift its focus from recreation to raw material production to help with the war effort. However, after the war, the forest received a larger number of recreation visitors than had ever been seen before. In 1957, the Forest Service began Operation Outdoors, a five-year program to improve and expand the recreation infrastructure on the National Forests across the country. The program was unofficially a competitive response to the National Park Service’s “Mission 66”  program, a 10-year building program in anticipation of NPS’ 50th anniversary in 1966.3

program, a 10-year building program in anticipation of NPS’ 50th anniversary in 1966.3

From 1933 to 1955, the number of recreation visitors to the National Forests of Oregon and Washington grew from 771,000 to 5,192,000.4 This trend continues to the present day with about 2.3 million visitors per year to the Mt. Hood National Forest alone. With its 1.1 million acres, the Forest hosts many recreational activities for all – including camping, hiking, skiing and snowshoeing, sledding, hunting, boating and fishing, and more – in its 100+ developed campgrounds, 5 ski areas, and 800+ miles of recreational trails.In addition to recreation, the watersheds that start in the Forest help provide drinking water for one-third of Oregon’s entire population. While the Forest goes through periods of change, the Forest Service has continued to provide recreational facilities and opportunities for Oregonians and other visitors, as well as helping to preserve the history and landscape of the Forest for generations to come.

Other History Resources

- Bagby Hot Spring

- Barlow Road Tollgate

- Clackamas Lake Guard Station

- Cloud Cap Inn

- Lost Lake Resort

- Olallie Meadows

- Silcox Hut

- Ski Bowl Warming Hut

- Summer Homes Tracts

- Tilly Jane

- Timberline Lodge

[1] Hunn, Eugene S., Nchi’i-Wàna (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 134.

[2] John D. Unruh, The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840–60 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 119: https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/ows/seminarsflvs/UnruhTables.pdf

[3] Wayne D. Iverson, “Landscape Architects and the US Forest Service,” Paper presented to the USDA Forest Service Inter-Regional Landscape Architects Workshop at the Doubletree Hotel in Tucson, Arizona, May 21, 1990.

[4] Regional Forester, “A Glimpse of the Forest Situation in Oregon and Washington,” (Portland, OR: USDA Forest Service, July 1936), 23-24; Gerald J. Coutant, “A Chronology of the Recreation History of the National Forests and the U.S.D.A. Forest Service: 1940 to 1990,” Region 6 Internal Heritage Files, 4-6.