| FEIS Home Page |

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia

|

|

|

| Roundleaf greenbrier leaves. WikiMedia image by Fepup. | Roundleaf greenbrier fruits in winter. WikiMedia image by SB_Johnny - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/ |

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia Introductory

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Carey, Jennifer H. 1994. Smilax rotundifolia. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/vine/smirot/all.html []. Revisions: On 2 March 2018, the common name of this species was changed in FEIS from: common greenbrier to: roundleaf greenbrier. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION: SMIROT SYNONYMS: Smilax rotundifolia L. var. crenulata Small & A. Heller Smilax rotundifolia L. var. quadrangularis (Muhl. ex Willd.) Alph. Wood [34,40,43] NRCS PLANT CODE [48]: SMRO COMMON NAMES: roundleaf greenbrier common greenbrier TAXONOMY: The scientific name of roundleaf greenbrier is Smilax rotundifolia L. (Smilacaceae) [13,31]. LIFE FORM: Vine FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: None OTHER STATUS: Roundleaf greenbrier is listed as rare in Canada [1]. It is the only woody monocot in southern Canada [22].

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

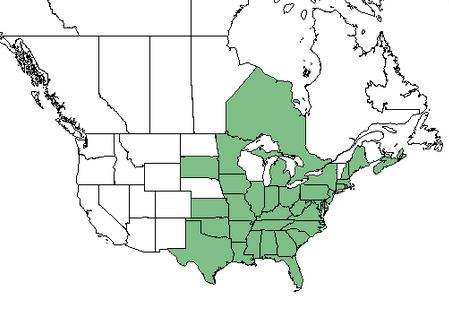

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION: Roundleaf greenbrier occurs throughout the eastern United States. Its range extends as far north as southern Nova Scotia and southern Ontario and continues west to southern Michigan, Indiana, and southern Illinois; south through southeastern Missouri to eastern Texas; and east to northern Florida [13,14,31,34].

|

| Distribution of roundleaf greenbrier. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [2018, April 9] [48]. |

ECOSYSTEMS: FRES10 White - red - jack pine FRES11 Spruce - fir FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine FRES14 Oak - pine FRES15 Oak - hickory FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress FRES17 Elm - ash - cottonwood FRES18 Maple - beech - birch STATES: AL AR CT DE FL GA IL IN KY LA ME MD MA MI MS MO NH NJ NY NC OH OK PA RI SC TN TX VT VA WV NS ON BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS: NO-ENTRY KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS: K089 Black Belt K095 Great Lakes pine forest K097 Southeastern spruce-fir forest K098 Northern floodplain forest K100 Oak - hickory forest K103 Mixed mesophytic forest K104 Appalachian oak forest K106 Northern hardwoods K110 Northeastern oak - pine forest K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest K112 Southern mixed forest K113 Southern floodplain forest SAF COVER TYPES: 20 White pine - northern red oak - red maple 21 Eastern white pine 23 Eastern hemlock 30 Red spruce - yellow birch 32 Red spruce 44 Chestnut oak 45 Pitch pine 46 Eastern redcedar 53 White oak 70 Longleaf pine 79 Virginia pine 81 Loblolly pine 82 Loblolly pine - hardwood 83 Longleaf pine - slash pine 95 Black willow 97 Atlantic white-cedar 98 Pond pine 108 Red maple 110 Black oak HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES: Roundleaf greenbrier occurs in a wide variety of plant communities. Understory associates of roundleaf greenbrier in moist woods include mapleleaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), grape (Vitis spp.), flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis), cat greenbrier (Smilax glauca), cane (Arundinaria gigantea), eastern poison-ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). [2,12,18,17]. In Atlantic white-cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) communities in North Carolina, roundleaf greenbrier occurs with sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana), redbay (Persea borbonia), large gallberry (Ilex coriacea), hurrahbush (Lyonia lucida), blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), and cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea) [25]. In drier woods, heath balds, heath-shrub communities, and rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.) thickets, roundleaf greenbrier occurs with black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), hillside blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), and low sweet blueberry (V. angustifolia). Other associates of dry sites include mountain-laurel (Kalmia latifolia), swamp dog-laurel (Leucothoe axillaris), Carolina holly (Ilex ambigua), and mountain white-alder (Clethra acuminata) [6,42,44]. Roundleaf greenbrier occurs in old fields with black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), blackberry (Rubus spp.), blueberry, and bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) [12].

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE: Numerous birds and animals eat roundleaf greenbrier fruits. The persistent fruits are an important late winter and early spring food for wintering birds including northern cardinals and white-throated sparrows [2]. White-tailed deer and lagomorphs browse the foliage [4,12,15,16]. Roundleaf greenbrier forms impenetrable thickets of prickly branches which probably create good cover for small mammals and birds. PALATABILITY: The green canes, tender shoots, and leaves are palatable to white-tailed deer [15,16]. NUTRITIONAL VALUE: Ehrenfeld [9] determined nitrogen concentrations of roundleaf greenbrier leaves and new twigs from four wetland communities in the New Jersey pine barrens. Nitrogen concentrations were 1.28 percent dry weight in the floodplain community, 1.52 in the pine lowlands, 1.89 in the wet hardwoods, and 2.09 in the dry hardwoods. Nitrogen concentrations of roundleaf greenbrier stems on all sites averaged 0.61 percent dry weight [9]. COVER VALUE: NO-ENTRY VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES: NO-ENTRY OTHER USES AND VALUES: NO-ENTRY OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS: Niering and Goodwin [29] recommend roundleaf greenbrier and other clonal shrubs for right-of-way clearings where trees interfere with powerlines. Dense roundleaf greenbrier, hillside blueberry, and black huckleberry thickets resisted invasion of trees for at least 15 years in a right-of-way from which trees were originally removed by herbicide application. In Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, roundleaf greenbrier was more important close to trails than in inaccessible areas, suggesting that it is resistant to disturbance [19]. Medium and heavy thinning of a Louisiana loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) plantation increased greenbrier (Smilax spp.) productivity [4]. Greenbriers (Smilax spp.) are resistant to most herbicides [47]. Two years after a late summer application of glyphosate, roundleaf greenbrier foliage appeared normal and healthy [41]. Propagation and eradication techniques are described for roundleaf greenbrier [12].

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS: Roundleaf greenbrier is a native liana that uses tendrils to climb 10 to 20 feet (3-6 m). The leathery leaves are deciduous, although sometimes tardily so in the southeastern states. The stems are usually quadrangular and diffusely branched with flattened prickles up to 0.3 inches (0.8 cm) long. The fruit is a berry [13,14,31,40]. Roundleaf greenbrier has long, slender, nontuberous rhizomes near the soil surface [14,15,24]. Roundleaf greenbrier canes live 2 to 4 years [15]. RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM: Phanerophyte Chamaephyte REGENERATION PROCESSES: Roundleaf greenbrier regenerates by rhizomes and seed. Rhizomes persist for years after the plant has been top-killed by fire or other disturbance [15]. On mesic sites in Connecticut dominated by shrubs, roundleaf greenbrier clones averaged 10 inches (25 cm) of radial expansion a year. On xeric sites where drought and browsing by lagomorphs restricted growth, roundleaf greenbrier clones decreased an average of 2 inches (5 cm) a year [29]. On sites in Ontario, roundleaf greenbrier did not spread vegetatively [22]. Roundleaf greenbrier produces some fruit every year [30]. Seeds are dispersed by animals and water [26]. Seeds often germinate when disturbance increases the amount of light on the soil and brings buried seeds to the surface [30]. Pogge and Bearce [30] tested roundleaf greenbrier seeds for total and potential germination. Exposure to light substantially increased germination. Seeds stored for 5 years at 36 to 45 degrees Fahrenheit (2-7 deg C) and about 2 percent moisture content had high viability. SITE CHARACTERISTICS: Roundleaf greenbrier is generally a submesic species, but extends onto subxeric and xeric sites [42]. It occurs on a wide variety of sites; these include south slopes and ridgetops in the southern Appalachian Mountains [6,42], low damp flatwoods on the lower Atlantic Coastal Plain [14], the inland coastal plain of Nova Scotia [33], and banks of freshwater swamps in Massachusetts [7]. Optimum soil pH is 5.0 to 6.0 [12]. SUCCESSIONAL STATUS: Roundleaf greenbrier is a pioneering species as well as a component of forest understories. Although it grows in low light conditions, roundleaf greenbrier is also capable of relatively high photosynthetic rates in full sunlight [5]. Shading of 10 to 20 percent of full sunlight may be optimal, but good fruit production occurred in 70 to 80 percent shade in West Virginia [12]. Roundleaf greenbrier is often found on recently logged sites, roadsides, and old fields [12,13,20]. Once vines such as roundleaf greenbrier become established on disturbed sites, they may dominate the early successional stages [26]. Hemond and others [20] use roundleaf greenbrier cover greater than 5 percent as an indicator of 40- to 50-year-old forests of old-field origin in southern Connecticut. Roundleaf greenbrier declined more than 50 percent over 20 years of observation in this forest [20]. SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT: Roundleaf greenbrier flowers from April to May in the southeastern states [21,31,43], from May to June in the northeastern states [12,13], and in June in southern Canada [34,35]. Fruits ripen in the fall. All annual growth is completed in a short time in the spring [12].

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia FIRE ECOLOGY

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS: Roundleaf greenbrier resists fire by sprouting from rhizomes [15,27,28]. Canopy openings caused by fire may favor roundleaf greenbrier. FIRE REGIMES: Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes". POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY: Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia FIRE EFFECTS

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT: Roundleaf greenbrier is top-killed by fire [46]. PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE: Roundleaf greenbrier sprouts from rhizomes after fire. Roundleaf greenbrier responded with vigorous vegetative reproduction to spring and fall prescribed fires in eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) and eastern white pine-hardwood forests in New Hampshire. The fires were of low intensity, with flames greater than 20 inches (50 cm) high, and burned only the surface litter layer [46]. Roundleaf greenbrier sprouted after an early March headfire in a young eastern Texas loblolly pine-shortleaf pine (P. echinata)-hardwood forest. The fire consumed 80 to 90 percent of the previous year's needle and leaf fall and about 50 percent of the older accumulated litter. The average roundleaf greenbrier height 2 years after the fire was 46 inches (118 cm) with an average of 1.60 stems per plant. Average height on the unburned control was 187 inches (476 cm) with an average of 1.73 stems per plant [37]. Annual and biennial early April fires were conducted in little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) grasslands in Connecticut [27,28]. The study sites were on agricultural lands abandoned 40 to 60 years previously and had up to 40 percent woody cover of clonal shrubs. After 15 years of burning, roundleaf greenbrier frequency increased over prefire levels on one plot but decreased slightly on another due to heavy lagomorph use of succulent postfire shoots. Cover of roundleaf greenbrier changed very little during the 18-year study, so the authors classified roundleaf greenbrier as a persistent species rather than an increaser. On unburned plots adjacent to the burns, roundleaf greenbrier increased in cover and frequency over the duration of the study.

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS: Roundleaf greenbrier foliage was sampled 1 and 2 years after low-severity and high-severity fires and compared to roundleaf greenbrier foliage in unburned areas. The first growing season after the low-severity fire, roundleaf greenbrier protein content was 7.8 percent higher than on unburned areas, but no difference was detected the second postfire growing season. One and two years after the high-severity fire, the protein contents were 6 percent and 19 percent higher, respectively, than foliage from unburned areas. Neither fire produced substantial changes in total solids, ash, ether content, crude fiber, or nitrogen-free extract [8]. Greenbrier spp. (Smilax rotundifolia and S. laurifolia) are a component of several fuel models for the coastal plain of North Carolina. They contribute to ladder fuels in the high pocosin type. Greenbrier intertwines with grass species in some types, impeding foot travel [45].

SPECIES: Smilax rotundifolia REFERENCES

1. White, D. J.; Maher, R. V.; Argus, G. W. 1982. Smilax rotundifolia L. In: Argus, George W.; White, David J., eds. Atlas of the rare vascular plants of Ontario. Part 1. Ottawa, ON: National Museums of Canada, National Museum of Natural Sciences. 1 p. [23478]

2. Baird, John W. 1980. The selection and use of fruit by birds in an eastern forest. Wilson Bulletin. 92(1): 63-73. [10004]v3. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p. [434]

4. Blair, Robert M. 1960. Deer forage increased by thinnings in a Louisiana loblolly pine plantation. Journal of Wildlife Management. 24(4): 401-405. [16891]

5. Carter, Gregory A.; Teramura, Alan H. 1988. Vine photosynthesis and relationships to climbing mechanics in a forest understory. American Journal of Botany. 75(7): 1011-1018. [9317]

6. Crandall, Dorothy L. 1958. Ground vegetation patterns of the spruce-fir area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Ecological Monographs. 28(4): 337-360. [11226]

7. Cross, Shirley G. 1992. An indigenous population of Clintonia borealis (Liliaceae) on Cape Cod. Rhodora. 94(877): 98-99. [18125]

8. DeWitt, James B.; Derby, James V., Jr. 1955. Changes in nutritive value of browse plants following forest fires. Journal of Wildlife Management. 19(1): 65-70. [7343]

9. Ehrenfeld, Joan G. 1986. Wetlands of the New Jersey Pine Barrens: the role of species composition in community function. American Midland Naturalist. 115(2): 301-313. [8650]

10. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

11. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others]. 1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

12. Smith, Robert L. 1974. Greenbriers: common greenbrier; cat greenbrier. In: Gill, John D.; Healy, William M, compilers. Shrubs and vines for northeastern wildlife. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-9. Upper Darby, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: 54-58. [23408]

13. Gleason, Henry A.; Cronquist, Arthur. 1991. Manual of vascular plants of northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. 2nd ed. New York: New York Botanical Garden. 910 p. [20329]

14. Godfrey, Robert K.; Wooten, Jean W. 1981. Aquatic and wetland plants of southeastern United States: Dicotyledons. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press. 933 p. [16907]

15. Goodrum, Phil D. 1977. Greenbriers/Smilax spp. In: Halls, Lowell K., ed. Southern fruit-producing woody plants used by wildlife. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-16. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Region, Southern Forest Experiment Station: 111-116. [23479]

16. Goodrum, Phil D.; Reid, Vincent H. 1958. Deer browsing in the longleaf pine belt. In: Proceedings, 58th annual meeting of the Society of American Foresters; 1958 September 28-October 2; Salt Lake City, UT. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters: 139-143. [17023]

17. Greller, Andrew M. 1977. A classification of mature forests on Long Island, New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 104(4): 376-382. [22020]

18. Gunasekaran, M.; Weber, D. J.; Sanderson, S.; Devall, Margaret M. 1992. Reanalysis of the vegetation of Bee Branch Gorge Research Natural Area, a hemlock-beech community on the Warrior River Basin of Alabama. Castanea. 57(1): 34-45. [20436]

19. Hall, Christine N.; Kuss, Fred R. 1989. Vegetation alteration along trails in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. Biological Conservation. 48: 211-227. [9306]

20. Hemond, Harold F.; Niering, William A.; Goodwin, Richard H. 1983. Two decades of vegetation change in the Connecticut Arboretum Natural Area. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 110(2): 184-194. [9045]

21. Hunter, Carl G. 1989. Trees, shrubs, and vines of Arkansas. Little Rock, AR: The Ozark Society Foundation. 207 p. [21266]

22. Kevan, Peter G.; Ambrose, John D.; Kemp, James R. 1991. Pollination in an understorey vine, Smilax rotundifolia, a threatened plant of the Carolinian forests in Canada. Canadian Journal of Botany. 69: 2555-2559. [17567]

23. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York: American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

24. Martin, Ben F.; Tucker, S. C. 1985. Developmental studies in Smilax (Liliaceae). I. Organography and the shoot apex. American Journal of Botany. 72(1): 66-74. [15086]

25. Moore, Julie H.; Carter, J. H., III. 1987. Habitats of white cedar in North Carolina. In: Laderman, Aimlee D., ed. Atlantic white cedar wetlands. [Place of publication unknown]: Westview Press: 177-190. [15877]

26. Newling, Charles J. 1990. Restoration of bottomland hardwood forests in the lower Mississippi Valley. Restoration & Management Notes. 8(1): 23-28. [14611]

27. Niering, William A. 1981. The role of fire management in altering ecosystems. In: Mooney, H. A.; Bonnicksen, T. M.; Christensen, N. L.; [and others], technical coordinators. Fire regimes and ecosystem properties: Proceedings of the conference; 1978 December 11-15; Honolulu, HI. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-26. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 489-510. [5084]

28. Niering, William A.; Dreyer, Glenn D. 1989. Effects of prescribed burning on Andropogon scoparius in postagricultural grasslands in Connecticut. American Midland Naturalist. 122: 88-102. [8768]

29. Niering, William A.; Goodwin, Richard H. 1974. Creation of relatively stable shrublands with herbicides: arresting "succession" on rights-of-way and pastureland. Ecology. 55: 784-795. [8744]

30. Pogge, Franz L.; Bearce, Bradford C. 1989. Germinating common and cat greenbrier. Tree Planters' Notes. 40(1): 34-37. [23409]

31. Radford, Albert E.; Ahles, Harry E.; Bell, C. Ritchie. 1968. Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. 1183 p. [7606]

32. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

33. Roland, A. E. 1991. Coastal-plain plants in inland Nova Scotia. Rhodora. 93(875): 291-298. [16490]

34. Roland, A. E.; Smith, E. C. 1969. The flora of Nova Scotia. Halifax, NS: Nova Scotia Museum. 746 p. [13158]

35. Soper, James H.; Heimburger, Margaret L. 1982. Shrubs of Ontario. Life Sciences Misc. Publ. Toronto, ON: Royal Ontario Museum. 495 p. [12907]

36. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

37. Stransky, John J.; Halls, Lowell K. 1979. Effect of a winter fire on fruit yields of woody plants. Journal of Wildlife Management. 43(4): 1007-1010. [9660] v 38. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 1994. Plants of the U.S.--alphabetical listing. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 954 p. [23104]

39. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Survey. [n.d.]. NP Flora [Data base]. Davis, CA: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Biological Survey. [23119]

40. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Southwest. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1104 p. [7707]

41. Wendel, G. W.; Kochenderfer, J. N. 1982. Glyphosate controls hardwoods in West Virginia. Res. Pap. NE-497. Upper Darby, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station. 7 p. [9869]

42. Whittaker, R. H. 1956. Vegetation of the Great Smoky Mountains. Ecological Monographs. 26(1): 1-79. [11108]

43. Wofford, B. Eugene. 1989. Guide to the vascular plants of the Blue Ridge. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press. 384 p. [12908]

44. Reiners, W. A. 1965. Ecology of a heath-shrub synusia in the pine barrens of Long Island, New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 92(6): 448-464. [22835]

45. Wendel, G. W.; Storey, T. G.; Byram, G. M. 1962. Forest fuels on organic and associated soils in the coastal plain of North Carolina. Station Paper No. 144. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 46 p. [21669]

46. Chapman, Rachel Ross; Crow, Garrett E. 1981. Application of Raunkiaer's life form system to plant species survival after fire. Torrey Botanical Club. 108(4): 472-478. [7432]

47. Bovey, Rodney W. 1977. Response of selected woody plants in the United States to herbicides. Agric. Handb. 493. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 101 p. [8899]

48. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

FEIS Home Pagehttps://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/vine/smirot/all.html