Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Torreya californica

|

|

|

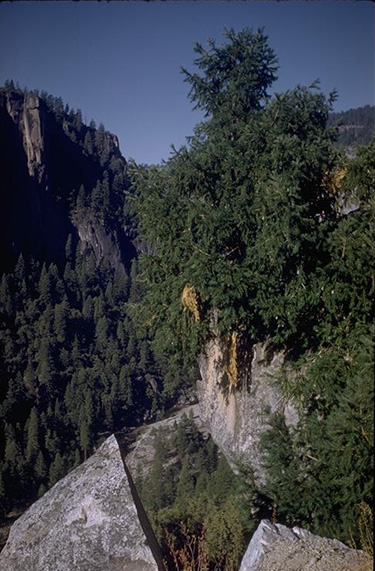

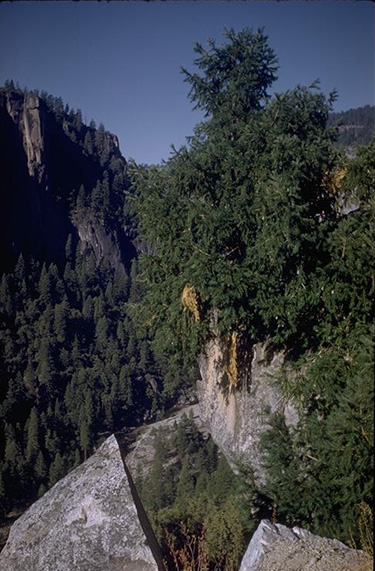

| Califoria nutmeg in Yosemite Valley. Image by Charles Webber © 1998 California Academy of Sciences. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Torreya californica

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Howard, Janet L. 1992. Torreya californica. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/torcal/all.html [].

Updates: On 01 Janurary 2018, the common name of this species was changed in FEIS from: California torreya

to: California nutmeg. Pictures were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

TORCAL

SYNONYMS:

Tumion californicum (Torr.) Greene

SCS PLANT CODE:

TOCA

COMMON NAMES:

California nutmeg

California torreya

stinking cedar

stinking nutmeg

stinking yew

TAXONOMY:

The currently accepted scientific name of California nutmeg is Torreya

californica Torr.; it is in the yew family (Taxaceae) [12,16]. There

are no subspecies, varieties, or forms [3].

LIFE FORM:

Tree

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Torreya californica

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

California nutmeg is endemic to California. Its range has two distinct

parts: one in the Coast Ranges and one in the Cascade-Sierra Nevada

foothills. In the Coast Ranges, it is distributed from southwest

Trinity County south to Monterey County. In the Cascade-Sierra Nevada

foothills, it is distributed from Shasta County south to Tulare County

[8]. Although not rare, it is not an abundant species. Local

occurrence is widely scattered throughout its range [3], and trees are

often infrequent in these localities [8].

|

| Distribution of California nutmeg. Map from USGS: 1971 USDA, Forest Service map provided by Thompson and others [30]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES20 Douglas-fir

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES24 Hemlock - Sitka spruce

FRES27 Redwood

FRES28 Western hardwoods

FRES34 Chaparral - mountain shrub

STATES:

CA

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

3 Southern Pacific Border

4 Sierra Mountains

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K001 Spruce - cedar - hemlock forest

K005 Mixed conifer forest

K006 Redwood forest

K007 Red fir forest

K011 Western ponderosa forest

K012 Douglas-fir forest

K025 Alder - ash forest

K029 California mixed evergreen forest

K030 California oakwoods

K033 Chaparral

SAF COVER TYPES:

207 Red fir

213 Grand fir

221 Red alder

224 Western hemlock

229 Pacific Douglas-fir

230 Douglas-fir - western hemlock

232 Redwood

234 Douglas-fir - tanoak - Pacific madrone

243 Sierra Nevada mixed conifer

244 Pacific ponderosa pine - Douglas-fir

245 Pacific ponderosa pine

246 California black oak

249 Canyon live oak

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

California nutmeg is plastic is its habitat requirements, and occurs in

many diverse plant communities. In the Coast Ranges, it grows in

chaparral and various coastal forests such as redwood (Sequoia

sempervirens). It is associated with canyon live oak (Quercus

chrysolepis) and California bay (Umbellularia californica) woodlands in

both coastal and inland foothill regions [10]. Inland populations are

most commonly found in the ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) belt [3,8].

It is rare in chaparral communities of the Cascade-Sierra Nevada. It is

not a dominant or indicator species in community or vegetation typings.

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Torreya californica

WOOD PRODUCTS VALUE:

Commercial harvesting of California nutmeg is almost nonexistent due to

scant availability. It was logged on a limited basis in the past,

especially where growing in association with redwood, but was never an

important timber species. The fine-grained yellow-brown wood is,

however, highly attractive and of good quality. It is strong and

elastic, smooth in texture, polishes well, and emits a fragrance similar

to that of sandalwood [3]. It is highly durable. Trees cut over 100

years ago have been found lying on the ground with little rot [17]. The

wood was historically used for making cabinets, wooden turnware, and

novelty items; and for fuel and fenceposts [3].

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

Various animals eat California nutmeg seeds [21].

PALATABILITY:

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

California nutmeg provides watershed protection and increases wildlife

habitat diversity [3,21]. Sites where it has been eliminated or reduced

in numbers would benefit from repopulation. Historical records of such

sites are sparse, but a few are known. Logging during the early 1900's

eliminated California nutmeg from the Vaca Mountains of Napa and Solano

counties, and considerably reduced populations in the Santa Cruz

Mountains and lower Russian River area of Sonoma County [3]].

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

California nutmeg is sometimes planted as an ornamental, but the

disagreeable odor of the needles detracts from its desirability. The

seed oil has potential use in cooking, being similar in quality to olive

and pine-nut oils. Seeds of a related Asian species, Torreya nucifera,

are harvested in Japan for rendering into high-quality cooking oil.

California nutmeg seeds are edible, reportedly tasting somewhat like

peanuts [4].

The seeds were a highly esteemed food of California Indians. In

addition, Indians used the tree roots for making baskets [4], and the

wood for making bows [18].

Unlike Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), a related species, California

nutmeg is not harvested as a source of taxol [1] because it produces

taxol in only extremely small quantities. It is used as a control,

however, when testing other species with potential for taxol production

[22].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

If thinning of California nutmeg stands is necessary, care should be

taken to preserve both male and female trees as near to each other as

possible in order to facilitate natural regeneration [24]. Favorable

sites for potential natural regeneration such as canyon bottoms and

lowland flats are unlikely to support seedlings if there is heavy

logging or other disturbance above catchment areas [3].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Torreya californica

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

California nutmeg is a dioecious native evergreen tree, typically from

16.5 to 90 feet (5-30 m) tall and 8 to 20 inches (20-51 cm) in diameter

[16,21]. A record tree growing near Fort Bragg measured 141 feet (43 m)

in height and 14.8 feet (4.5 m) in d.b.h. until cut by timber thieves

[17]. The crown is pyramidal to irregular in shape [10,19]. Needles

persist for many years. The bark is thin, from 0.3 to 0.5 inch (0.8-1.3

cm) on mature trees [19]. Roots are described as "deep" [14]. The

large, heavy seeds are from 1 to 1.4 inches (2.5-3.0 cm) long, enveloped

by a drupelike aril [16,21].

|

| CAlifornia nutmeg arils. Image by Robert Potts © 2001 California Academy of Sciences. |

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Male California nutmeg bear their microsporophylls within strobili. In

contrast, the ovules of female trees are not contained within strobili

but are solitary [16]. Male strobili begin growth the year prior to

flowering, while females trees develop ovules in one growing season

[21]. Torreyas are wind pollinated [16]. Male trees must normally be

within 75 to 90 feet (23-27 m) of female trees in order to effect

pollination [24]. Seed production is erratic. Good seed crops may be

followed by crop failure the following year [10]. Seeds mature in 2

years [19]. Being heavy, seeds usually fall near the parent plant; wind

dissemination is rare [17]. Seed predation by Steller's and scrub jay

is high [10]. Seeds require a 9- to 12-month stratification period

before germination [21]. In one study, seeds stratified for 3 months

before planting took an additional 9 months to germinate under

greenhouse conditions. Ninety-two percent of seedlings germinated at

that time. [15]. Temperature regimes during the stratification period

were not noted. Seeds sometimes germinate without stratification but do

so slowly [21].

Growth of trees in the understory is slow [10]. Sudworth [24] reported

trees from 4 to 8 inches (10-20 cm) in diameter were 60 to 110 years of

age, while those from 12 to 18 inches (30-46 cm) in diameter were 170 to

265 years old. The growth rate needs further study, however, as rates

of over 1 foot (30 cm) per year have been reported in cultivars [3].

Preliminary data obtained from tree-ring counts of saplings on the El

Dorado National Forest shows some trees attained heights of 4.8 feet

(1.5 m) in 28 years [10].

California nutmeg sprouts from the roots, root crown, and bole

following damage to aboveground portions of the tree [3,10,19]. Some

nutmegs reproduce by layering [21], but the layering capacity of

California nutmeg is unknown.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

California nutmeg grows in diverse sites such as streambanks, shaded

slopes, hot dry canyons, canyon floors, and lowland flats [3]. Best

growth occurs on moist sites. Trees in Colusa County grow in serpentine

soil [8].

The climate is mediterranean, characterized by hot, dry summers and

cool, wet winters. Summer climate is moderated in the outer Coast

Ranges by cool marine air and fog [29].

California nutmeg grows at elevations from 3,000 to 7,000 feet

(914-2,134 m) [16].

Plant associations: Common overstory associates not listed under

Distribution and Occurrence include tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflora),

Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia), California bay (Umbellularia

californica), bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), white alder (Alnus

rhombifolia), and bishop pine (Pinus muricata). Understory associates

include cascara (Rhamnus purshiana), ceanothus (Ceanothus spp.),

manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.), Pacific rhododendron (Rhododendron

macrophyllum), California huckleberry (Vaccinium ovatum), California red

huckleberry (V. parvifolium), and Pacific bayberry (Myrica californica)

[12,28].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

California nutmeg is very shade tolerant [9] and is found in late seral

and climax communities [3]. Following disturbance such as fire or

logging, sprouts growing from surviving perennating buds appear in

initial communities [10].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

Stamens and arils are produced from March through May [16,21]. Seeds

ripen from August until October and are released from September through

November [15,21,27].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Torreya californica

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

California nutmeg sprouts from the roots, root crown, and bole

following top-kill by fire [5,10,19].

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Tree with adventitious-bud root crown/root sucker

Geophyte, growing points deep in soil

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Torreya californica

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

Fire usually top-kills all size classes of this thin-barked species. A

few large trees have survived fire but were badly scarred [10].

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

California nutmeg sprouts from the roots, root crown, and bole

following fire [5,10,19]. Rate of recovery is not recorded in the literature.

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

NO-ENTRY

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Torreya californica

REFERENCES:

1. Bailey, C. D. pers. comm. 1992

2. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

3. Burke, J. G. 1975. Human use of the California nutmeg tree, Torreya

californica, and other members of the genus. Economic Botany. 29:

127-139. [19267]

4. Chestnut, V. K. 1900. Plants used by the Indians of Mendocino Co.,

California. Contrib. U.S. Nat. Herberium. 7(1): 305-306. [19268]

5. Conard, S. G. pers. comm. 1992

6. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

7. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

8. Griffin, James R.; Critchfield, William B. 1972. The distribution of

forest trees in California. Res. Pap. PSW-82. Berkeley, CA: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and

Range Experiment Station. 118 p. [1041]

9. Hamilton, Ronald C. 1991. Single-tree selection method: An uneven-aged

silviculture system. In: Genetics/silviculture workshop proceedings;

1990 August 27-31; Wenatchee, WA. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Timber Management Staff: 46-84. [16562]

10. Hunter, J. pers. comm. 1992

11. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

12. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native

and naturalized). Agric. Handb. 541. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 375 p. [2952]

13. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

14. Maino, E.; Howard, F. 1955. Ornamental trees. Berkeley, CA: University

of California Press. [19271]

15. Mirov, N. T.; Kraebel, C. J. 1937. Collecting and propagating the seeds

of California wild plants. Res. Note No. 18. Berkeley, CA: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, California Forest and Range

Experiment Station. 27 p. [9787]

16. Munz, Philip A. 1973. A California flora and supplement. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press. 1905 p. [6155]

17. Murray, M. D. 1985. The California nutmeg. American Forests. 91: 40-51.

[19266]

18. Peattie, D. C. 1953. A natural history of western trees. Boston, MA:

Houghton Mifflin Co. 751 p. [19269]

19. Preston, Richard J., Jr. 1948. North American trees. Ames, IA: The Iowa

State College Press. 371 p. [1913]

20. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

21. Roy, Douglass F. 1974. Torreya Arn. Torreya. In: Schopmeyer, C. S.,

ed. Seeds of woody plants in the United States. Agriculture Handbook No.

450. Washington: U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service:

815-816. [7768]

22. Snader, K. pers. comm. 1992

23. Stalter, Richard. 1990. Torreya taxifolia Arn. Florida torreya. In:

Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics

of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 601-603. [13420]

24. Sudworth, G. B. 1908. Forest trees of the Pacific Slope. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 441 p. [19270]

25. Trush, William J.; Connor, Edward C.; Knight, Allen W. 1989. Alder

establishment and channel dynamics in a tributary of the South Fork Eel

River, Mendocino County, California. In: Abell, Dana L., technical

coordinator. Proceedings of the California riparian systems conference:

Protection, management, and restoration for the 1990's; 1988 September

22-24; Davis, CA. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-110. Berkeley, CA: U.S. Department

of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range

Experiment Station: 14-21. [13509]

26. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. 1982.

National list of scientific plant names. Vol. 1. List of plant names.

SCS-TP-159. Washington, DC. 416 p. [11573]

27. Van Dersal, William R. 1938. Native woody plants of the United States,

their erosion-control and wildlife values. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture. 362 p. [4240]

28. Westman, W. E.; Whittaker, R. H. 1975. The pygmy forest region of

northern California: studies on biomass and primary productivity.

Journal of Ecology. 63: 493-520. [8186]

29. Zinke, Paul J. 1977. The redwood forest and associated north coast

forests. In: Barbour, Michael G.; Major, Jack, eds. Terrestrial

vegetation of California. New York: John Wiley and Sons: 679-698.

[7212]

30. Thompson, Robert S.; Anderson, Katherine H.; Bartlein, Patrick J. 1999.

Digital representations of tree species range maps from "Atlas of United

States trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications), [Online].

In: Atlas of relations between climatic parameters and distributions of

important trees and shrubs in North America. Denver, CO: U.S. Geological

Survey, Information Services (Producer). Available: esp.cr.usgs.gov/data/little/

[2015, May 12]. [82831]

FEIS Home Page