Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

|

|

|

| Pond cypress. Creative Commons image by Clinton Steeds from Los Angeles, USA. |

Bald cypress. Creative Commons image by Gerald J. Lenhard, Louisiana State University, Bugwood.org. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Coladonato, Milo 1992. Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/taxspp/all.html [].

Updates: On 6 February 2018, the common and scientific names of these cpesies weere changed in FEIS

from: Taxodium distichum var. imbricarium, pondcypress to: Taxodium ascendens, pond cypress, and

from: Taxodium distichum var. distichum, baldcypress to: Taxodium distichum, bald cypress.

Maps and images were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

TAXSPP

TAXDIS

TAXASC

SYNONYMS:

for Taxodium ascendens:

Taxodium distichum var. imbricarium (Nuttall) Croom [34,56,59]

Taxodium distichum. var. nutans (misapplied)[56,59,60]

for Taxodium distichum:

Taxodium distichum var. distichum [34,56,59]

Taxodium distichum var. nutans (Ait.) Sweet [12,53]

NRCS PLANT CODE:

TADI2

TAAS

COMMON NAMES:

cypress

pond cypress

bald cypress

white cypress

Gulf cypress

southern cypress

red cypress

swamp cypress

yellow cypress

TAXONOMY:

This review covers two species of cypress (Taxodium):

Taxodium ascendens Brogn. [26,47,57,58], pond cypress

Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich.[47], bald cypress

Morphology: Pond cypress is less likely than bald cypress to have knees,

and when it does have them, they are shorter and more rounded. Its

fluted base tends to have rounded rather than sharp ridges and its bark

is usually more coarsely ridged. Its branches are more ascending than

those of bald cypress. Seedlings and fast-growing shoots of pond cypress,

however, resemble those of bald cypress. Despite the usual

differences in the two species, it is sometimes very difficult to

distinguish them [39,53].

Habitat: Pond cypress grows in shallow ponds and wet areas westward only to

southeastern Louisiana. It does not usually grow in rivers or stream

swamps. Bald cypress is more widespread and typical of the species. Its range

extends westward into Texas and northward into Illinois and Indiana [12,53].

The name "cypress" is used in this review when referring to both

species collectively.

LIFE FORM:

Tree

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

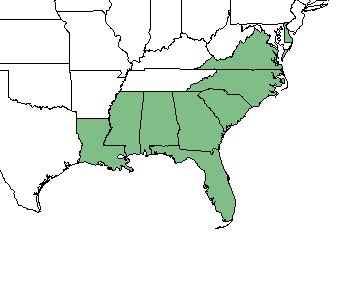

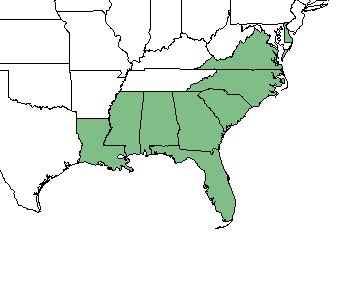

Pond cypress is generally confined to areas from

southeastern Virginia to southern Florida and southeastern Louisiana

[11,18,36].

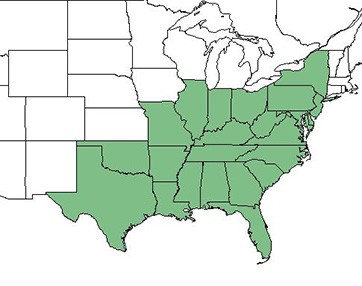

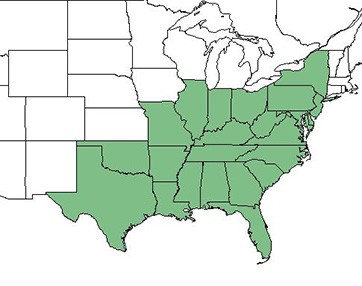

Bald cypress grows along the Atlantic Coastal Plain from southern

Delaware to southern Florida, westward along the lower Gulf Coast Plain

to southeastern Texas almost to the Mexican border. Inland, it grows

along streams of the Southeastern States and north in the Mississippi

Valley to southeastern Oklahoma, southeastern Missouri, southern

Illinois, and southwestern Indiana [11,18,36]. It is cultivated in

Hawaii [55].

|

|

| Distribution of pond cypress and bald cypress, respectively. Maps courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [47]. [2018, February 6]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES15 Oak - hickory

FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress

STATES:

AL AR DE FL GA HI IL IN KY LA

MD MS MO NC OK SC TN TX VA

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

NO-ENTRY

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K089 Black Belt

K090 Live oak- sea oats

K091 Cypress savanna

K092 Everglades

K105 Mangrove

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

K112 Southern mixed forest

K113 Southern floodplain forest

K114 Pocosin

K115 Sand pine scrub

K116 Subtropical pine forest

SAF COVER TYPES:

74 Cabbage palmetto

83 Longleaf pine - slash pine

84 Slash pine

85 Slash pine - hardwood

92 Sweetgum - willow oak

97 Atlantic white cedar

98 Pond pine

100 Pondcypress

101 Baldcypress

102 Baldcypress - tupelo

103 Water tupelo - swamp tupelo

104 Sweetbay - swamp tupelo - redbay

106 Mangrove

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

Bald cypress has been included as an indicator or dominant in the

following vegetation types:

The phytosociology of the Green Swamp, North Carolina [32]

Southern mixed hardwood forest of north-central Florida [38]

Plant communities in the marshlands of southeastern Louisiana [41]

Plant communities of the Coastal Plain of North Carolina and their

successional relations [52].

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

WOOD PRODUCTS VALUE:

Bald cypress wood is highly resistant to decay, making it valuable for a

multitude of uses [8]. It is used in building construction, fence

posts, planking in boats, doors, blinds, flooring, shingles, caskets,

interior trim, and cabinetry [11,46,51].

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

Bald cypress seeds are eaten by wild turkey, wood ducks, evening

grosbeak, and squirrels. The seed is a minor part of the diet of

waterfowl and wading birds. Yellow-throated warblers forage in the

Spanish moss often found hanging on the branches of old cypress trees

[4,48,53]. Cypress domes provide watering places for a variety of

birds, mammals, and reptiles of the surrounding pinelands [31].

PALATABILITY:

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE:

The tops of cypress trees provide nesting sites for bald eagles and

ospreys. Warblers use the old decaying knees for nesting cavities, and

catfish spawn below cypress logs. Cypress domes provide breeding sites

for a number of frogs, toads, and salamanders. Cypress domes also

provide nesting sites for herons and egrets [22,30].

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

Bald cypress has been successfully planted on the margins of surface-

mined lakes in southern Illinois, southwestern Indiana, and western

Kentucky [9].

Cypress swamps help to maintain high regional water tables, and they can

also be used to provide advanced wastewater treatment for small

communities [21]. Research has shown that cypress domes can serve as

tertiary sewage treatment facilities for improving water quality and

recharging groundwater [25].

Methods of collecting, extracting, cleaning, storing, and sowing

bald cypress seeds to produce nursery-grown seedlings have been

described [48,53].

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

Bald cypress has been planted as a water tolerant tree species used for

shading and canopy closure to help reduce populations of the Anopheles

mosquito [5].

Bald cypress has been successfully planted throughout its range as an

ornamental and along roadsides [11].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Silviculture: Canopy thinning has been reported as the best management

practice for regenerating cypress. Thinning controls competition and

allows overhead light for newly germinated seedlings [20,53].

Animal damage: The swamp rodent nutria often clips or uproots newly

planted cypress seedlings before the root systems are fully established,

thus killing the seedlings. When nutria populations are high, entire

plantings are often destroyed in a few days [43].

Insects and disease: The fungus Stereum taxodi causes brown pocket rot

known as "pecky cypress" that attacks the heartwood of older living

bald cypress trees. The fungus most often gains entrance in the crown

and works its way down, destroying a considerable part of the heartwood

at the base of the tree [53]. The forest tent caterpillar (Malacosma

disstria) and fruit-tree leafroller (Archips argyrospila) larvae webb

and feed on cypress needles as soon as the buds break and small leaflets

expand, causing dieback and sometimes mortality [27,53].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Cypress is a large-sized, native, deciduous, conifer, frequently 100 to

120 feet (30-37 m) in height. It is slow growing and very long-lived.

Individual trees have been reported up to 1,200 years old in Georgia and

South Carolina [19,26]. In the forest, bald cypress typically has a

broad, irregular crown, often draped in curtains and streams of gray

Spanish moss. The trunks of older trees are massive, tapering, and

particularly when growing in swamps, buttressed at the base [11]. The

deciduous leaves are linear and flat with blades mostly spreading,

fastened alternately around the twig. Cypress is monoecious with its

male and female flowers forming slender tasslelike structures near the

edge of the branchlets [10,53]. The bark of cypress is usually quite

thin and fibrous with an interwoven pattern of narrow flat ridges and

narrow furrows. Cypress develops a taproot as well as horizontal roots

that lie just below the surface and extend 20 to 50 feet (6-15 m) before

bending down [19,21].

Knees: Cypress knees are a unique polymorphic structure of cypress

trees. They start out as small swellings on the upper surface of a

horizontal root and then protrude above the mud and water providing

extra needed support. They vary in height from 1 to 12 feet (0.3-3.7 m)

depending on the level of the water [21].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Seed production and dispersal: Bald cypress produces seed every year,

and good seed production occurs at intervals of about 3 years

[15,20,53]. Because of the large size of the seeds and the relatively

small wing size, cypress seeds are not dispersed to any distance by the

wind. Flood waters disperse the seed along rivers and streams

[12,37,40].

Seedling development: The exact requirements for moisture immediately

after seed dispersal seems to be the key to the survival and

distribution of cypress. Under swamp conditions, the best seed

germination generally takes place on a sphagnum moss or a wet-muck

seedbed. An abundant supply of moisture for a period of 1 to 3 months

after seedfall is required for germination. Seed covered with water for

as long as 30 months may germinate when the water recedes. On better

drained soils, seed usually fails to germinate successfully because of

the lack of surface water [10,16,53].

Vegetative reproduction: After disturbance, cypress will sprout from

the stumps of young trees. Trees up to 60 years of age send up healthy

sprouts. Trees up to 200 years of age may also sprout but not very

vigorously [10,24].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

Cypress is usually restricted to very wet soils consisting of muck,

clay, or fine sand where moisture is abundant and fairly permanent

[1,3,38]. More than 90 percent of the natural cypress stands are found

on flat or nearly flat topography at elevations less than 100 feet (30

m) above sea level. The upper limits of its growth in the Mississippi

Valley is at an elevation of about 500 feet (152 m) [6,13,28].

Common tree associates of bald and pond cypress are: American elm (Ulmus

americana), water hickory (Carya aquatica), red maple (Acer rubrum),

green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), sugarberry (Celtis laevigata),

sweetgum (Liquidambar sylvatica), loblolly-bay (Gordonia lasianthus),

and sweetbay (Magnolia virginia) [39,42,53].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

Cypress swamps represent an edaphic climax; they are held almost

indefinitely in a subfinal stage of succession by physiographic

conditions [17,38,42]. Cypress is intermediate in shade tolerance.

Best growth occurs under a high degree of overhead light, but the tree

persists under partial shade [17,20,51,53].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

The flower buds of cypress trees appear in late December or early

January. The flowers appear in March and April; fruit ripens from

October through December [7,29].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

Ecology: Because of its edaphic and physiographic requirements (See

Site Characteristics), cypress is usually protected from fire [2,30].

Adaptation: The thin bark of cypress trees offers little protection

against fire and, during years of drought when swamps are dry, fire

kills great quantities of cypress [11,50].

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Tree with adventitious-bud root crown/soboliferous species root sucker

Secondary colonizer - off-site seed

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

Under drought conditions, peat fires that burn below the surface of the

organic soil may kill the roots of cypress trees, thus killing the

plant. A peat fire in the Okefenokee swamp in Florida killed 97 percent

of the cypress trees in a 3,000-acre plot (1,214 ha) [14,45].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

NO-ENTRY

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

Cypress will often sprout from the stump when top-killed by fire [49].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Fire is not recommended as a management tool for maintaining cypress

stands. Severe fires after logging or drainage may destroy seeds and

roots in the soil, favoring replacement of cypress by willows (Salix

spp.) and subsequent hardwoods [21,49].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Taxodium ascendens, T. distichum

REFERENCES:

1. Abernethy, Y.; Turner, R. E. 1987. US forested wetlands: 1940-1980:

Field-data surveys document changes and can guide national resource

management. BioScience. 37(10): 721-727. [10575]

2. Abramson, Julie. 1977. Swamps burn too. Conservation News. 42(20): 8-10.

[11475]

3. Allen, James A.; Kennedy, Harvey E., Jr. 1989. Bottomland hardwood

reforestation in the lower Mississippi Valley. Slidell, LA: U.S.

Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wetlands

Research Center; Stoneville, MS: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Southern Forest Experimental Station. 28 p. [15293]

4. Anon. 1978. Wondrous woodie. Virginia Wildlife. 39(11): 12-13. [17367]

5. Bates, A. Leon; Pickard, Eugene; Dennis, Michael. 1979. Tree plantings -

a diversified management tool for reservoir shorelines. In: Johnson, R.

Roy; McCormick, J. Frank, technical coordinators. Strategies for

protection and management of floodplain wetlands & other riparian

ecosystems: Proc. of the symposium; 1978 December 11-13; Callaway

Gardens, GA. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-12. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service: 190-194. [4360]

6. Beaven, George Francis; Oosting, Henry J. 1939. Pocomoke Swamp: a study

of a cypress swamp on the eastern shore of Maryland. Bulletin of the

Torrey Botanical Club. 66: 376-389. [14507]

7. Bonner, F. T. 1974. Liquidambar styraciflua L. sweetgum. In:

Schopmeyer, C. S., ed. Seeds of woody plants in the United States.

Agriculture Handbook No. 450. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service: 505-507. [7695]

8. Bowers, Lynne Jordan; Melhuish, John H., Jr. 1988. Silcon content in

wood and bark of baldcypress compared to loblolly pine and southern red

oak. Transactions of the Kentucky Academy of Science. 49(1-2): 1-7.

[15037]

9. Brothers, Timothy S. 1988. Indiana surface-mine forests: historical

development and composition of a human-created vegetation complex.

Southeastern Geographer. 28(1): 19-33. [8787]

10. Brown, Clair A. 1984. Morphology and biology of cypress trees. In: Ewel,

Katherine Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. Cypress swamps. Gainesville, FL:

University of Florida Press: 16-24. [14780]

11. Collingwood, G. H. 1937. Knowing your trees. Washington, DC: The

American Forestry Association. 213 p. [6316]

12. Conner, William H.; Toliver, John R. 1990. Observations on the

regeneration of baldcypress (Taxodium distichum [L.] Rich.) in Louisiana

swamps. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry. 14(3): 115-118. [13275]

13. Coultas, Charles L.; Duever, Michael J. 1984. Soils of cypress swamps.

In: Ewel, Katherine Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. Cypress swamps.

Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press: 51-59. [14844]

14. Cypert, Eugene. 1961. The effects of fires in the Okefenokee Swamp in

1954 and 1955. American Midland Naturalist. 66(2): 485-503. [11018]

15. Dean, George W. 1969. Forests and forestry in the Dismal Swamp. Virginia

Journal of Science. 20: 166-173. [17249]

16. Deghi, Gary S. 1984. Seedling survival and growth rates in experimental

cypress domes. In: Ewel, Katherine Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. Cypress

swamps. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press: 141-144. [14846]

17. Duever, Michael J.; Riopelle, Lawrence A. 1983. Successional sequences

and rates on tree islands in the Okefenokee Swamp. American Midland

Naturalist. 110(1): 186-191. [14590]

18. Duncan, Wilbur H.; Duncan, Marion B. 1987. The Smithsonian guide to

seaside plants of the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts from Louisiana to

Massachusetts, exclusive of lower peninsular Florida. Washington, DC:

Smithsonian Institution Press. 409 p. [12906]

19. Duncan, Wilbur H.; Duncan, Marion B. 1988. Trees of the southeastern

United States. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press. 322 p.

[12764]

20. Ewel, Katherine C. 1990. Multiple demands on wetlands. Bioscience.

40(9): 660-666. [14596]

21. Ewel, Katherine C. 1990. Swamps. In: Myers, Ronald L.; Ewel, John J.,

eds. Ecosystems of Florida. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida

Press: 281-322. [17392]

22. Ewel, Katherine Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. 1984. Cypress swamps.

Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. 472 p. [14778]

23. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

24. Franklin, Jerry F.; DeBell, Dean S. 1973. Effects of various harvesting

methods on forest regeneration. In: Hermann, Richard K.; Lavender, Denis

P., eds. Even-age management: Proceedings of a symposium; 1972 August 1;

[Location of conference unknown]. Paper 848. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State

University, School of Forestry: 29-57. [16239]

25. Fritz, Walter R.; Helle, Steven C.; Ordway, James W. 1984. The cost of

cypress wetland treatment. In: Ewel, Kathernine Carter; Odum, Howard T.,

eds. Cypress swamps. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press:

239-248. [17648]

26. Godfrey, Robert K. 1988. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of northern

Florida and adjacent Georgia and Alabama. Athens, GA: The University of

Georgia Press. 734 p. [10239]

27. Goyer, Richard A.; Linhard, Gerald J.; Smith, James D. 1990. Insect

herbivores of a bald-cypress/tupelo ecosystem. Forest Ecology and

Management. 33/34: 517-521. [11936]

28. Gresham, Charles A. 1989. A literature review of effects of developing

pocosins. In: Hook, Donal D.; Lea, Russ, eds. Proceedings of the

symposium: The forested wetlands of the Southern United States; 1988

July 12-14; Orlando, FL. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-50. Asheville, NC: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest

Experiment Station: 44-50. [9228]

29. Gunderson, Lance H. 1984. Regeneration of cypress in logged and burned

strands at Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, Florida. In: Ewel, Katherine

Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. Cypress swamps. Gainesville, FL:

University of Florida Press: 349-357. [14857]

30. Hare, Robert C. 1965. Contribution of bark to fire resistance of

southern trees. Journal of Forestry. 63(4): 248-251. [9915]

31. Harris, Larry D.; Vickers, Charles R. 1984. Some faunal community

characteristics of cypress ponds and the changes induced by

perturbations. In: Ewel, Katherine Carter; Odum, Howard T., eds. Cypress

swamps. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press: 171-185. [14849]

32. Kologiski, Russell L. 1977. The phytosociology of the Green Swamp, North

Carolina. Tech. Bull. No. 250. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Agricultural

Experiment Station. 101 p. [18348]

33. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

34. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native

and naturalized). Agric. Handb. 541. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 375 p. [2952]

35. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

36. Marsinko, Allan P. C.; Syme, John H.; Harris, Robert A. 1991. Cypress: a

species in transition. Forest Products Journal. 41(1): 61-64. [14593]

37. McCaughey, Ward W.; Weaver, T. 1991. Seedling submergence tolerance of

four western conifers. Tree Planters' Notes. 42(2): 45-48. [17340]

38. Monk, Carl D. 1965. Southern mixed hardwood forest of northcentral

Florida. Ecological Monographs. 35: 335-354. [9263]

39. Monk, Carl D.; Brown, Timothy W. 1965. Ecological consideration of

cypress heads in north-central Florida. American Midland Naturalist. 74:

126-140. [10848]

40. Newling, Charles J. 1990. Restoration of bottomland hardwood forests in

the lower Mississippi Valley. Restoration & Management Notes. 8(1):

23-28. [14611]

41. Penfound, W. T.; Hathaway, Edward S. 1938. Plant communities in the

marshlands of southeastern Louisiana. Ecological Monographs. 8(1): 3-56.

[15089]

42. Pessin, L. J. 1933. Forest associations in the uplands of the lower Gulf

Coastal Plain (longleaf pine belt). Ecology. 14(1): 1-14. [12389]

43. Platt, Steven G.; Brantley, Christopher G. 1990. Baldcypress swamp

restoration depends on control of nutria, vine mats, salinization.

Restoration and Management Notes. 8(1): 46. [15039]

44. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

45. Taylor, Dale L. 1980. Fire history and man-induced fire problems in

subtropical south Florida. In: Stokes, Marvin A.; Dieterich, John H.,

technical coordinators. Proceedings of the fire history workshop; 1980

October 20-24; Tucson, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-81. Fort Collins, CO: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and

Range Experiment Station: 63-68. [16044]

46. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1956. Wood...colors and

kinds. Agric. Handb. 101. Washington, DC. 36 p. [16294]

47. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (Producer).

Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

48. Vines, Robert A. 1960. Trees, shrubs, and woody vines of the Southwest.

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 1104 p. [7707]

49. Wade, Dale; Ewel, John; Hofstetter, Ronald. 1980. Fire in south Florida

ecosystems. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-17. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 125

p. [10363]

50. Wade, Dale D.; Johansen, R. W. 1986. Effects of fire on southern pine:

observations and recommendations. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-41. Asheville, NC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest

Experiment Station. 14 p. [10984]

51. Walker, Laurence C. 1990. Forests: A naturalist's guide to trees and

forest ecology. Wiley Nature Editions. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

288 p. [13763]

52. Wells, B. W. 1928. Plant communities of the Coastal Plain of North

Carolina and their successional relations. Ecology. 9(2): 230-242.

[9307]

53. Wilhite, L. P.; Toliver, J. R. 1990. Taxodium distichum (L.) Rich.

baldcypress. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical

coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric.

Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service: 563-572. [13416]

54. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

55. St. John, Harold. 1973. List and summary of the flowering plants in the

Hawaiian islands. Hong Kong: Cathay Press Limited. 519 p. [25354]

56. Flora of North America Association. 2008. Flora of North

America: The flora, [Online]. Flora of North America Association

(Producer). Available: http://www.fna.org/FNA. [36990]

57. Radford, Albert E.; Ahles, Harry E.; Bell, C. Ritchie. 1968.

Manual of the vascular flora of the Carolinas. Chapel Hill, NC: The

University of North Carolina Press. 1183 p. [7606]

58. Wunderlin, Richard P.; Hansen, Bruce F. 2003. Guide to the

vascular plants of Florida. 2nd edition. Gainesville, FL: The

University of Florida Press. 787 p. [69433]

59. Farjon, Alijos. 1998. World checklist and bibliography of conifers.

2nd ed. Kew, England: The Royal Botanic Gardens. 309 p. [61059]

60. Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 2014. Flora of North

America north of Mexico, [Online]. Flora of North America Association

(Producer). Available: http://www.efloras.org/flora_page.aspx?flora_id=1. [36990]

FEIS Home Page

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/taxspp/all.html