Index of Species Information

|

|

|

| Typical variety of slash pine (left) and Florida slash pine (right). Images by William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org, and Chris M. Morrism, respectively. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION :

Carey, Jennifer H. 1992. Pinus elliottii. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/pinell/all.html [].

ABBREVIATION :

PINELL

PINELLE

PINELLD

SYNONYMS :

Pinus densa (Little & Dorman) Gaussen

Pinus caribaea Morelet (misapplied)

Pinus heterophylla (Ell.) Sudworth

SCS PLANT CODE :

PIEL

COMMON NAMES :

slash pine

yellow slash pine

swamp pine

Florida slash pine

South Florida slash pine

Dade County slash pine

Dade County pine

Cuban pine

TAXONOMY :

The scientific name of slash pine is Pinus elliottii Engelm.

There are two geographic varieties [23,24]:

Pinus elliottii var. elliottii, slash pine (typical variety)

Pinus elliottii var. densa Little & Dorman, Florida slash pine

There is a transitional zone where morphological traits of the two

varieties show clinal variation. Both varieties will be discussed in

this report with emphasis on the typical slash pine variety, P. elliottii

var. elliottii.

Slash pine occasionally hybridizes with loblolly pine (P. taeda),

late flowering sand pine (P. clausa), and early flowering longleaf pine

(P. palustris) [23,24].

LIFE FORM :

Tree

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS :

No special status

OTHER STATUS :

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

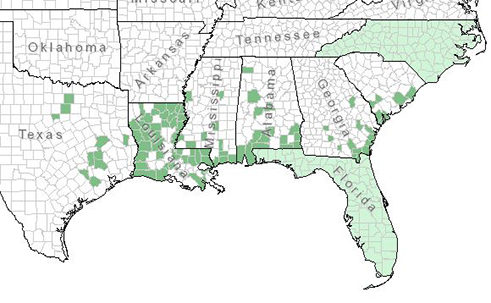

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION :

The native range of the typical slash pine variety includes the Coastal

Plain from southern South Carolina to central Florida and west to

eastern Louisiana. Slash pine has been planted as far north as Kentucky

and Virginia [37], and as far west as eastern Texas, where it now

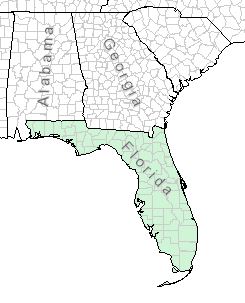

reproduces naturally [24]. Florida slash pine occurs in central

and southern Florida and in the lower Florida Keys [2,24].

|

|

| Overall disritbution of slash pine (above), and distributions of typical variety of slash pine (lower left) slash pine and Florida slash pine (lower right). Maps courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC [2018, June 12] [37]. |

ECOSYSTEMS :

FRES12 Longleaf - slash pine

FRES13 Loblolly - shortleaf pine

FRES14 Oak - pine

FRES16 Oak - gum - cypress

STATES :

AL AR FL GA KY LA MS NC OK SC

TN TX VA

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS :

NO-ENTRY

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS :

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

K112 Southern mixed forest

K113 Southern floodplain forest

K114 Pocosin

K116 Subtropical pine forest

SAF COVER TYPES :

70 Longleaf pine

74 Cabbage palmetto

81 Loblolly pine

82 Loblolly pine - hardwood

83 Longleaf pine - slash pine

84 Slash pine

85 Slash pine - hardwood

97 Atlantic white cedar

98 Pond pine

100 Pond cypress

103 Water tupelo - swamp tupelo

104 Sweetbay - swamp tupelo - redbay

111 South Florida slash pine

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES :

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES :

The published classifications listing slash pine as dominant in

community types (cts) are presented below:

Area Classification Authority

SC general veg. cts Nelson 1986

se US: Gulf Coast general forest cts Pessin 1933

se US general forest cts Waggoner 1975

se US general veg. cts Christensen 1988

nc FL general forest cts Monk 1968

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

WOOD PRODUCTS VALUE :

Slash pine is an important timber species in the southeastern United

States. Its strong, heavy wood is excellent for construction purposes.

Because of its high resin content, the wood is also used for railroad

ties, poles, and piling [7,24,26,27].

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE :

Slash pine seeds are eaten by birds and small mammals. Cattle and deer

occasionally browse seedlings [24]. In the St. Vincent National

Wildlife Refuge of northwestern Florida, slash pine made up 0.7 percent

of Indian sambar deer rumens and 0.6 percent of white-tailed deer rumens

[34].

The dense foliage of slash pine provides cover and shelter for wildlife

[24]. The endangered red-cockaded woodpecker is known to nest in slash

pine, although it is not this cavity dweller's preferred species [15].

Large slash pine provide nest sites for bald eagles [48].

PALATABILITY :

NO-ENTRY

NUTRITIONAL VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

COVER VALUE :

NO-ENTRY

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES :

Because of slash pine's rapid growth, it is used to stabilize soil and

rehabilitate mine spoils. It grows well on coal mine spoils in

northern Alabama [24,40].

OTHER USES AND VALUES :

Slash pine is the preferred naval stores species. Its resin is used for

gum turpentine and rosin production [24,41].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

Slash pine forest management requires integration of three primary uses:

turpentine, wood, and forage production. Intense production and

management for one use will likely reduce production for another use.

For instance, turpentining reduces slash pine growth by 25 percent while

the tree is worked, a closed canopy reduces understory forage

production, and fire used to improve forage production and quality may

damage young trees [26].

Slash pine is best regenerated using even-aged management. Both the

seed tree and shelterwood silviculture systems are effective. For

adequate regeneration, leave 6 to 10 seed trees per acre and 25 to 40

shelterwood trees per acre. Overstory trees should be removed 1 to 3

years after seedlings are established. Seedbed preparation increases

seedling establishment. Pine growth is enhanced by site preparation and

removal of hardwood and saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) understory

competition [22].

Cattle grazing is extensive on pine flatwoods in the Southeast. Pearson

[31] reported that light to moderate grazing did not affect

establishment, survival, or growth of seeded or planted slash pine up to

5 years old. Heavy grazing decreased survival, but most losses occurred

in the first year. It is recommended that cattle be withheld from

grazing young stands until after the first growing season [31].

Disease: The two most serious diseases of slash pine are fusiform rust

(Cronartium quercuum f. sp. fusiforme) and annosus root rot

(Heterobasidion annosum) [22,24]. Fusiform rust is a stem disease that

affects seedlings and saplings. The younger the pine is when it becomes

infected, the more likely it is to die [35]. Removing trees with severe

stem galls minimizes timber losses and improves stand quality [3].

Annosus root rot infects thinned stands. The fungus colonizes on

freshly cut stumps and spreads by root contact. Thick litter is

associated with sporophore development [9]. Annosus root rot is most

damaging to slash pine if there is good surface drainage. Slash pine

grown on shallow soils with a heavy subsoil clay layer are not

susceptible to annosus root rot [24].

Lophodermella cerina, a needle-blight-causing fungus, mainly affects

slash pine close to metropolitan areas. Air pollution is thought to

worsen this disease [38]. Pitch canker, caused by Fusarium moniliforme

var. subglutinans, is common in plantations and can girdle a pine [24].

Insects: Insects that attack slash pine include pales weevil (Hylobius

pales), black turpentine beetle (Dendroctonus terebrans), engraver

beetles (Ips spp.), and defoliators such as pine web worm (Tetralopha

robustella), blackheaded pine sawfly (Neodiprion excitans), redheaded

pine sawfly (N. lecontei), and Texas leafcutting ant (Atta texana) [24].

Florida slash pine is less susceptible to insects and disease than

the typical variety of slash pine. Grass-stage seedlings of

Florida slash pine are attacked by brown-spot needle blight (Scirrhia

acicola) [24].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS :

Slash pine is a native evergreen conifer with thick platy bark and

relatively long needles. It grows rapidly and lives approximately 200

years. Slash pine has an extensive lateral root system and a moderate

taproot [24]. The typical slash pine variety has a straight bole and a

narrow ovoid crown. Mature trees of this variety vary in height from 60

to 100 feet (18-30.5 m) and average 24 inches (61 cm) in d.b.h. [13].

The two varieties differ considerably in morphology. Florida

slash pine has longer needles, smaller cones, denser wood, and a thicker

and longer taproot [24]. The trunk forks into large spreading branches

which form a broad, rounded crown [13,46]. Mature trees attain only 56

feet (17 m) in height. The relatively short stature of Florida

slash pine probably evolved to avoid tropical storm damage [21].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM :

Phanerophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES :

Seed production and dissemination: Slash pine is monoecious. Trees

usually begin producing cones between 10 and 15 years of age. Good cone

crops occur every 3 years for the typical variety and every 4 years for

the South Florida variety. Ninety percent of the light, winged seeds

fall within 150 feet (46 m) of the source tree [24].

Germination and seedling development: Germination is epigeal and occurs

within 2 weeks of seedfall. Slash pine seeds have good viability.

Exposed mineral soil enhances germination [24].

Open-grown seedlings of the typical slash pine variety grow 16 inches

(41 cm) in the first year. Root development is best in clayey soil and

worst in sandy soil [24].

Seedlings of the South Florida variety have a 2- to 6-year grass stage

similar to that of longleaf pine. During the grass stage, seedlings

develop an extensive root system and a thick root collar. Once

initiated, height growth is rapid [13]. Florida slash pine

seedlings are more drought and flood tolerant than those of the typical

variety [1,2].

Vegetative reproduction: Florida slash pine grass-stage seedlings

can sprout from the root collar if top-killed [24].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS :

Slash pine grows in a warm, humid climate and up to about 500 feet (150

m) in elevation. Slash pine grows best on mesic flatwood sites and on

pond or stream margins where soil moisture is ample but not excessive,

and drainage is poor [24]. Established stands grow well on flooded

sites, but flooding restricts seedling establishment [14]. Soils

include Spodosols, Ultisols, and Entisols. Slash pine's native range

was probably more restricted by frequent fire than by soil types or soil

moisture. With fire suppression, slash pine has spread to drier sites

[2,14].

The Florida slash pine variety grows from near sea level to about

70 feet (20 m) in elevation [8]. This variety grows in a wide range of

conditions, from wet sites in the northern part of its range to

well-drained sandy soils and rocky limestone outcrops in the South

[2,21].

Tree associates of slash pine include live oak (Quercus virginiana),

water oak (Q. nigra), post oak (Q. stellata), blackjack oak (Q.

marilandica), myrtle oak (Q. myrtifolia), bluejack oak (Q. incana),

turkey oak (Q. laevis), southern red cedar (Juniperus silicicola), pond

cypress (Taxodium ascendens), cabbage palmetto (Sabal palmetto), red

maple (Acer rubrum), and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) [8].

Understory species on drier sites include pineland threeawn (Aristida

stricta), bluestem (Andropogon spp.), saw-palmetto (Serenoa repens),

gallberry (Ilex glabra), fetterbush (Lyonia lucida), and pitcher plant

(Sarracenia spp.). On moist to wet sites, understory species include

southern bayberry (Myrica cerifera), buckwheat-tree (Cliftonia

monophylla), yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), and dahoon (I. cassine).

Undergrowth on very wet sites is primarily Sphagnum spp. [8].

More than fifteen species of herbs are endemic to the Miami rock ridge

pinelands where Florida slash pine dominates [36].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS :

Slash pine is relatively intolerant of competition and intolerant of

shade [24]. It will reproduce in small openings and invade open

longleaf pine stands, but growth is reduced by competition and partial

shade [22]. Slash pine invades fallow agricultural fields and disturbed

areas. It will invade longleaf pine stands where fire has been absent

for at least 5 to 6 years. In the absence of fire, slash pine flatwoods

are replaced by southern mixed hardwood forests on drier sites and by

bayheads on wetter sites [29].

Florida slash pine may be an edaphic or fire climax on flatwood

sites [8]. In the absence of fire, this variety is also replaced by

hardwoods. In pine rocklands, hardwood succession is rapid, but in pine

flatwoods, vegetative changes occur more slowly [42].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT :

Male strobili begin to develop in June, grow for several weeks, and then

go dormant until midwinter. Pollen is shed from late January to

February. Female strobili begin to develop in late August and grow

until they are fully developed. Cones mature in September,

approximately 20 months after pollinization. Seed fall is in October

[24].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS :

Young slash pine is susceptible to fire, but mature trees are fire

resistant [4]. Thick bark and high, open crowns allow individuals to

survive fire. Slash pine, however, is less fire resistant than longleaf

or sand pine [27]. Seedlings grow fast, and in 10 to 12 years slash

pine is resistant to fire that does not crown [46].

Estimates of the natural fire frequency of slash pine flatwoods range

from 3 to 15 fires per century [8,21]. A fire interval of at least 5 to

6 years allows young trees to develop some fire resistance. Fires are

ignited by lightning in late spring and summer [10,41]. Ample soil

moisture and seasonally wet depressions and drainages of slash pine

habitat impede fire entry. Occasional fire serves to reduce hardwood

competition and expose mineral soil which enhances germination [21,24].

The bark structure of slash pine is important to its fire resistance.

Outer bark layers overlap and protect grooves where the bark is thinner

[6]. The platy bark flakes off to dissipate heat [21].

The South Florida variety is more fire resistant than the typical

variety because seedlings and saplings have thicker bark [1,2,24,42].

The estimated natural fire frequency of Florida slash pine

communities is 25 fires per century [21]. Crown fires are rare because

frequent fires reduce fuel build-up, trees self-prune well, and stands

are open [1]. In addition to adaptations of the typical slash pine

variety, the South Florida variety is fire resistant in the seedling

grass stage. A dense tuft of needles protects the terminal bud. If

top-killed by fire, the grass-stage seedling may sprout from the root

collar [45]. See the longleaf pine review for further information on

grass-stage seedlings.

FIRE REGIMES :

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY :

Crown-stored residual colonizer; short-viability seed in on-site cones

off-site colonizer; seed carried by wind; postfire years one and two

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT :

One- and two-year-old slash pine are killed by low-severity fire. After

3 to 4 years, seedlings survive low-severity fire but not

moderate-severity fire. Ten- to fifteen-foot-tall (3.0-4.6 m) saplings

survive moderate-severity fires. Once slash pine is 10 to 12 years old,

it survives fire that does not crown [10,24,41,46].

Slash pine is tolerant of crown scorch. Scorched foliage is replaced by

new shoots. Slash pine as young as 5 years old may recover from 100

percent crown scorch [6,41]. Slash pine taller than 5 feet (1.5 m)

seldom die if less than 70 percent of the crown is scorched [26]. In

New South Wales, Australia, a fall wildfire burned a slash pine

plantation averaging 20 feet (6.1 m) in height. The fire crowned in

most areas. Trees with no green needles, few or no brown needles, and a

drooping apical branch had 31 percent survival, trees with mostly brown

needles and few or no green needles present had 93.8 percent survival,

and trees with clearly visible green needles at the top had 96.9 percent

survival [39].

Slash pine needles were killed instantly when immersed in water at 147

degrees Fahrenheit (64 deg C) but survived 9.5 minutes at 126 degrees

Fahrenheit (52 deg C) [5].

If slash pine bark is thicker than 0.6 inch (1.5 cm), mortality due to

cambium damage is unlikely from a low-severity fire. In one study,

0.08-inch (0.2 cm) thick bark protected the cambium from externally

applied heat at a temperature of 572 degrees Fahrenheit (300 deg C) for

1 minute. Bark which was 0.47 inch (1.2 cm) thick protected the cambium

from 1110 degrees Fahrenheit (600 deg C) for 2 minutes [6].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT :

Seedlings of the South Florida variety are more fire resistant than the

typical slash pine variety but less resistant than longleaf pine

seedlings [46]. In Florida, 2-year-old seedlings of both varieties

averaging 3 feet (0.9 m) in height were burned by wildfire in December.

Twenty-three percent of the South Florida variety burned by headfire and

56 percent burned by backfire survived. Less than one percent of the

typical variety survived either headfires or backfires. One-third of

the Florida slash pine survivors sprouted from dormant buds at or

near the root collar and along the bole. Root collar sprouts died back

after new needle growth appeared below the fire-killed leader [19].

A cool, prescribed winter fire in a Florida slash pine stand

killed many older pines, but young pines survived. Although there was

no outward sign of fire damage, fire may have killed the feeder roots,

and only young, vigorous pines were able to recover [43].

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE :

Slash pine's growth response to fire is variable. Slash pine damaged by

fire may suffer a short-term reduction in growth, although fires that

result in light or no scorch may actually enhance growth [41]. In the

Georgia Coastal Plain, a 9-year-old stand averaging 24.5 feet (7.5 m) in

height and 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) in d.b.h. was prescribed burned in

February. In the first postfire growing season, slash pine with 0 to 15

percent crown scorch outgrew the control, pine with 15 to 40 percent

crown scorch was not significantly different in growth from the control,

and pine with more than 40 percent scorch showed reduced growth. Growth

returned to normal in the second postfire growing season [16].

Severely scorched, 25-year-old slash pine in Georgia, averaging 8 inches

(20 cm) in d.b.h., lost almost a full year's growth in two growing

seasons. Growth of trees with less than 10 percent crown scorch was

only 85 percent of unburned trees after 2 years [17]. In Louisiana,

annual and biennial prescribed backfires initiated in a 4-year-old stand

averaging 7.8 feet (2.4 m) in height reduced growth, but trienniel fires

did not. Whether the fires were in May or March had no effect on growth

[12].

Height growth is slightly more sensitive to needle scorch than diameter

growth. McCulley [26] reported that height growth loss occurred in

trees with no crown scorch if they were smaller than 7 inches (18 cm) in

d.b.h., but diameter growth loss only occurred in trees with greater

than 30 percent crown scorch.

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE :

NO-ENTRY

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS :

If a poor seed crop is expected, prescribed burning should be done prior

to seedfall to enhance germination. Prescribed burning before stand

establishment also reduces fire hazard in young stands. Prescribed

burning at 3 to 5 year intervals throughout the stand rotation will

facilitate future seedbed preparation, and control but not eradicate

hardwoods. Hardwoods benefit wildlife and complete eradication is not

necessary. At the end of the rotation, successive summer fires can be

used for site preparation [22]. In the southern Florida pine rocklands,

fire every 3 to 7 years has effectively controlled hardwoods [42].

Young slash pine stands should not be burned for the first 5 years or

until the stand is 12 to 15 feet (3.7-4.6 m) tall [22,26,46]. Cattle

can be used to reduce fuel buildup until young pine stands are resistant

to light fire [12,46].

Prescribed winter and spring burning is usually done in pine flatwoods

every 2 to 3 years to increase range grasses for cattle [41].

In the Coastal Plain, prescribed burning before and after thinning

reduced infection by root rot caused by Heterobasidion annosum. The

fire destroyed the litter that is associated with sporophore development

of the fungus. A fungal competitor, Trichloderma spp., increased in the

soil after burning and may have contributed to the reduced infection

[9].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Pinus elliottii

REFERENCES :

1. Abrahamson, Warren G. 1984. Species response to fire on the Florida Lake

Wales Ridge. American Journal of Botany. 71(1): 35-43. [9608]

2. Abrahamson, Warren G.; Hartnett, David C. 1990. Pine flatwoods and dry

prairies. In: Myers, Ronald L.; Ewel, John J., eds. Ecosystems of

Florida. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Press: 103-149.

[17388]

3. Belanger, Roger P.; Zarnoch, Stanley J. 1991. Evaluating and predicting

tree mortality associated with fusiform rust in merchantable slash and

loblolly pine plantations. In: Coleman, Sandra S.; Neary, Daniel G.,

compilers. Proceedings, 6th biennial southern silvicultural research

conference: Volume 1; 1990 October 30 - November 1; Memphis, TN. Gen.

Tech. Rep. SE-70. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station: 289-298. [17483]

4. Brown, Arthur A.; Davis, Kenneth P. 1973. Forest fire control and use.

2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. 686 p. [15993]

5. Byram, G. M.; Nelson, R. M. 1952. Lethal temperatures and fire injury.

Res. Note No. 1. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 2 p. [16317]

6. de Ronde, C. 1982. The resistance of Pinus species to fire damage. South

African Forestry Journal. 122: 22-27. [9916]

7. Duncan, Wilbur H.; Duncan, Marion B. 1988. Trees of the southeastern

United States. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press. 322 p.

[12764]

8. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

9. Froelich, R. C.; Hodges, C. S., Jr.; Sackett, S. S. 1978. Prescribed

burning reduces severity of annosus root rot in the South. Forest

Science. 24: 93-100. [8332]

10. Garren, Kenneth H. 1943. Effects of fire on vegetation of the

southeastern United States. Botanical Review. 9: 617-654. [9517]

11. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

12. Grelen, Harold E. 1983. Comparison of seasons and frequencies of burning

in a young slash pine plantation. Res. Pap. SO-185. New Orleans, LA:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest

Experiment Station. 5 p. [10996]

13. Harlow, William M.; Harrar, Ellwood S., White, F. M. 1979. Textbook of

dendrology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. 510 p. [18070]

14. Hebb, Edwin A.; Clewell, Andre F. 1976. A remnant stand of old-growth

slash pine in the Florida panhandle. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical

Club. 103(1): 1-9. [12739]

15. Jackson, Jerome A. 1971. The evolution, taxonomy, distribution, past

populations and current status of the red-cockaded woodpecker. In:

Thompson, Richard L., ed. The ecology and management of the red-cockaded

woodpecker: Proceedings of a symposium; 1971 May 26-27; Folkston, GA.

Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 4-29. [17996]

16. Johansen, R. W. 1975. Prescribed burning may enhance growth of young

slash pine. Journal of Forestry. 73: 148-149. [12018]

17. Johansen, Ragnar W.; Wade, Dale D. 1987. Effects of crown scorch on

survival and diameter growth of slash pines. Southern Journal of Applied

Forestry. 11(4): 180-184. [11962]

18. Kartesz, John T.; Kartesz, Rosemarie. 1980. A synonymized checklist of

the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. Volume

II: The biota of North America. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North

Carolina Press; in confederation with Anne H. Lindsey and C. Richie

Bell, North Carolina Botanical Garden. 500 p. [6954]

19. Ketcham, D. E.; Bethune, J. E. 1963. Fire resistance of south Florida

slash pine. Journal of Forestry. 61: 529-530. [17992]

20. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

21. Landers, J. Larry. 1991. Disturbance influences on pine traits in the

southeastern United States. In: Proceedings, 17th Tall Timbers fire

ecology conference; 1989 May 18-21; Tallahassee, FL. Tallahassee, FL:

Tall Timbers Research Station: 61-95. [17601]

22. Langdon, O. Gordon; Bennett, Frank. 1976. Management of natural stands

of slash pine. Res. Pap. SE-147. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 12

p. [11853]

23. Little, Elbert L., Jr. 1979. Checklist of United States trees (native

and naturalized). Agric. Handb. 541. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 375 p. [2952]

24. Lohrey, Richard E.; Kossuth, Susan V. 1990. Pinus elliottii Engelm.

slash pine. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical

coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric.

Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service: 338-347. [13396]

25. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

26. McCulley, Robert D. 1950. Management of natural slash pine stands in the

Flatwoods of south Florida and north Florida. Circular No. 845.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. 57 p. [15016]

27. McCune, Bruce. 1988. Ecological diversity in North American pines.

American Journal of Botany. 75(3): 353-368. [5651]

28. McMinn, James W. 1969. Preparing sites for pine plantings in south

Florida. Res. Note SE-117. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 6

p. [11866]

29. Monk, Carl D. 1968. Successional and environmental relationships of the

forest vegetation of north central Florida. American Midland Naturalist.

79(2): 441-457. [10847]

30. Nelson, John B. 1986. The natural communities of South Carolina.

Columbia, SC: South Carolina Wildlife & Marine Resources Department. 54

p. [15578]

31. Pearson, H. A.; Whitaker, L. B.; Duvall, V. L. 1971. Slash pine

regeneration under regulated grazing. Journal of Forestry. 69: 744-746.

[13830]

32. Pessin, L. J. 1933. Forest associations in the uplands of the lower Gulf

Coastal Plain (longleaf pine belt). Ecology. 14(1): 1-14. [12389]

33. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

34. Shea, Stephen M.; Flynn, Les B.; Marchinton, R. Larry; Lewis, James C.

1990. Part 2. Social behavior, movement ecology, and food habits. In:

Ecology of sambar deer on St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge, Florida.

Bull. No. 25. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 13-62.

[17995]

35. Shoulders, Eugene; Scarborough, James H., Jr.; Arnold, Ray A. 1991.

Fusiform rust impact on slash pine under different cultural regimes. In:

Coleman, Sandra S.; Neary, Daniel G., compilers. Proceedings, 6th

biennial southern silvicultural research conference: Volume 1; 1990

October 30 - November 1; Memphis, TN. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-70. Asheville,

NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest

Experiment Station: 282-288. [17482]

36. Snyder, James R. 1991. Fire regimes in subtropical south Florida. In:

High-intensity fire in wildlands: management challenges and options:

Proceedings, 17th annual meeting of the Tall Timbers fire ecology

conference; 1991 May 18-21; Tallahassee, FL. Tallahassee, FL: Tall

Timbers Research Station: 303-319. [17068]

37. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018. PLANTS Database, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service

(Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/. [34262]

38. Van Deusen, Paul C.; Snow, Glenn A. 1991. Paired-tree study suggests

20-year recurrent slash pine blight. Canadian Journal of Forest

Research. 21: 1145-1148. [15419]

39. Van Loon, A. P. 1967. Some effects of a wild fire on a southern pine

plantation. Res. Note No. 21. New South Wales, Aust.: Forestry

Commission of New South Wales. 38 p. [14548]

40. Vogel, Willis G. 1981. A guide for revegetating coal minespoils in the

eastern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-68. Broomall, PA: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest

Experiment Station. 190 p. [15577]

41. Wade, Dale D. 1983. Fire management in the slash pine ecosystem. In:

Proceedings of the managed slash pine ecoystem; 1981; Gainesville, FL.

Gainesville, FL: University of Florida: School of Forest Resources and

Conservation: 203-227; 290-294; 301. [17997]

42. Wade, Dale; Ewel, John; Hofstetter, Ronald. 1980. Fire in South Florida

ecosystems. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-17. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 125

p. [10362]

43. Wade, Dale D.; Johansen, R. W. 1986. Effects of fire on southern pine:

observations and recommendations. Gen. Tech. Rep. SE-41. Asheville, NC:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest

Experiment Station. 14 p. [10984]

44. Waggoner, Gary S. 1975. Eastern deciduous forest, Vol. 1: Southeastern

evergreen and oak-pine region. Natural History Theme Studies No. 1, NPS

135. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park

Service. 206 p. [16103]

45. Ward, Daniel B. 1963. Contributions to the flora of Florida--2, Pinus

(Pinaceae). Castanea. 28(1): 1-10. [17991]

46. Wright, Henry A.; Bailey, Arthur W. 1982. Fire ecology: United States

and southern Canada. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 501 p. [2620]

47. Christensen, Norman L. 1988. Vegetation of the southeastern Coastal

Plain. In: Barbour, Michael G.; Billings, William Dwight, eds. North

American terrestrial vegetation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:

317-363. [17414]

48. Breininger, David R.; Smith, Rebecca B. 1992. Relationships between fire

and bird density in coastal scrub and slash pine flatwoods in Florida.

American Midland Naturalist. 127(2): 233-240. [17993]

FEIS Home Page

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/pinell/all.html