| FEIS Home Page |

|

|

|

Rocky Mountain juniper hybridizes with alligator juniper (J. deppeana) [55,65], creeping juniper (J. horizontalis) [1,41,46], oneseed juniper (J. monosperma) [55], Utah juniper (J. osteosperma), and eastern redcedar (J. virginiana) [40,41,46]. Relictual hybridization with eastern redcedar is documented in Texas [46]. There are numerous horticultural and ornamental varieties [55,65,90].

LIFE FORM:Distribution of some hybrids is: Juniperus scopulorum x J. virginiana in Nebraska,

North Dakota, and South Dakota [40,41,46]; J. scopulorum x J. horizontalis

in Montana, North Dakota, and Alberta [1,41,46]; J. scopulorum x J. deppeana across central

and north-central New Mexico, as well as in Walnut Canyon east of Flagstaff, Arizona [55,65];

J. scopulorum x J. osteosperma from Walnut Canyon north into Utah and east to Mesa Verde [55].

Distribution of Rocky Mountain juniper can also be accessed at

The Plants Database.

ECOSYSTEMS [48]:

FRES17 Elm-ash-cottonwood

FRES20 Douglas-fir

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES23 Fir-spruce

FRES25 Larch

FRES26 Lodgepole pine

FRES29 Sagebrush

FRES30 Desert shrub

FRES32 Texas savanna

FRES33 Southwestern shrubsteppe

FRES34 Chaparral-mountain shrub

FRES35 Pinyon-juniper

FRES36 Mountain grasslands

FRES38 Plains grasslands

FRES39 Prairie

FRES40 Desert grasslands

STATES:

| AZ | CO | ID | MT | NE |

| NV | NM | ND | OK | OR |

| SD | TX | UT | WA | WY |

| AB | BC | SK |

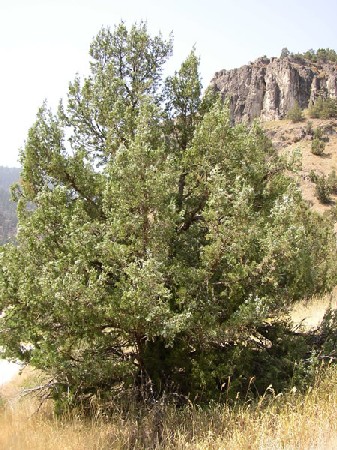

Rocky Mountain juniper communities in the northern Great Plains are often restricted to steep, north-facing slopes. Individuals may be scattered across other areas in mountains and canyons throughout the Rocky Mountain region, such as rocky outcrops, butte tops, draws, and floodplains [19,49,58,109]. Rocky Mountain juniper forms open woodland with sagebrush and grasses [122], and it is often found mixed with Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) [8,72,122], Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) [26,72], or ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) [26,72,109,122]. It is also found along waterways in pure stands or as understory in the cottonwood (Populus spp.)-willow (Salix spp.) habitat type [122]. It forms pure stands at middle and low elevations in the northern part of its range [90].

Classifications describing plant communities in which Rocky Mountain juniper

is a dominant species are as follows:

Colorado [4,66,118]

Wyoming [2,3,5,6,57,115]

Idaho [20,70,115]

Montana [57,59,60,88,101]

North Dakota [57]

South Dakota [5,57,68,117]

Utah [128]

Staminate cones are solitary at tips of branchlets, ovoid or mostly ellipsoid and 0.08-0.16 inch (2-4 mm) long [27,53,121]. Ovulate cones, or "berries", are solitary at the tips of branches and are fleshy with a resinous pulp. Berries are globose to subglobose, 0.16-0.31 inch (4-8 mm) in diameter [27,78,81,121]. Each contains 1-3 (up to 12) round seeds, 0.08-0.20 inch (2-5 mm) in diameter [27,53,65,82,121].

Rocky Mountain juniper is a long-lived species that often survives to be 250-300 years old or more [27,132]. A 36-foot (11 m) tall, 6.5-foot (2 m) diameter specimen near Logan, Utah was estimated at 3,000 years old [11,65,119,132].

Rocky Mountain juniper's morphological traits vary widely depending on climate, the presence of other species for hybridization, and other factors [28]. The preceding description provides characteristics of Rocky Mountain juniper relevant to fire ecology and is not meant to be used for identification. Detailed morphological descriptions and keys for identifying Rocky Mountain juniper are available [27,53].

RAUNKIAER [98] LIFE FORM:Pollination: Pollen is distributed mainly by wind in the spring [90].

Seed production: Rocky Mountain juniper may begin bearing seeds at 10-20 years of age, but the optimum age for seed production is 50-200 years. Trees can bear seed nearly every year, but heavier crops occur every 2-5 years [65,90,121]. The species is usually a prolific seeder, especially when stunted or growing in the open. Seeds are small, at 18,000-42,000 seeds per pound (8,000-19,000 seeds/kg) [65].

Seed dispersal: Rocky Mountain juniper ovulate cones ("berries") remain on the tree through the winter, unless consumed by birds or other animals, then ripen and fall from the tree in the 2nd spring [11]. The berries are dispersed mainly by birds, whose digestive tracts pass the seeds quickly with little effect on germination capability [26,65,69,78,82,87]. Bohemian waxwings are the primary dispersers and have been reported to pass 900 seeds in just 5 hours [11]. Other avian consumers include robins, solitaires, turkey, jays, and other waxwings [26,65,69,78,82,87]. Bighorn sheep, foxes, chipmunks, and other small mammals also help disperse seeds. Gravity and run-off provide another method of dissemination for the heavy berries that would otherwise fall and remain close to the parent tree [65,69,82].

Seed banking: Rocky Mountain juniper seeds do not germinate during the 1st spring following maturity, but germinate freely during the 2nd spring. The seeds require an "after-ripening" period of 14-16 months, during which moisture and chemical changes occur within the seeds [11,65,78,132].

Germination: Germinative capacity varies from 32-58% with an average of 45% [65,132]. The seeds may germinate more readily if fleshy covering is dissolved by digestive tract of a bird or other animal [11].

Seedling establishment/growth: Rocky Mountain juniper seedlings are generally sparse, possibly due to delayed germination and an inability to establish readily on dry sites. Seedlings are most successful in rocky crevices or other pockets with trapped moisture [11,65]. In nurseries, seedlings perform best with partial shade for the 1st year [65].

Rocky Mountain juniper is a slow-growing species. The average height of 8-year-old trees is 1 foot (0.3 m) [11,65]. Saplings grow slowly and steadily until age 40, when they average 13-14 feet (3.9-4.3 m) tall. Then growth slows, and at age 80, the average height is 18 feet (5.5 m). Thereafter trees grow about 0.55 foot (17 cm) per decade and reach 30 feet (9 m) in about 300 years. Diameter growth is also slow at about 0.79 inch (2 cm) per decade until about 170 years of age. Growth then declines slowly to about 0.255 inch (0.6 cm) per decade after age 210, and 300-year-old trees average 17 inches 0.4 m) diameter at 1 foot (0.3 m) above ground [65,119,132].

Asexual regeneration: Rocky Mountain juniper does not reproduce naturally from sprouts, but may be cultivated from cuttings [65,90,127]. For more information, see Other Management Considerations.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:Substrate: Rocky Mountain juniper prefers calcareous and somewhat alkaline soils and grows best on moist, deep soils [65]. The species is found on soils derived from basalt, limestone, sandstone, lavas, and shale. It also grows in many places where there is no developed soil [39,65,90].

Climate: Rocky Mountain juniper is generally found in dry, subhumid climates [90]. It also grows in moist, subhumid regions in the northern part of its range and in semiarid regions in the central and southern parts of its range [65]. The species can tolerate temperature extremes from -35 to 110º Fahrenheit (-37 to 43º C), but performs best where the average minimum temperature is greater than -10 to -5º Fahrenheit (-23 to -21º C). In its range, mean July temperatures range from 60 to 75º Fahrenheit (16 to 24 ºC) and mean January temperatures range from 15 to 40º Fahrenheit (-9 to 4º C) [65,90]. The average number of frost free days ranges from 120 in the northern Rockies to 175 at low elevations in Arizona and New Mexico [90]. Rocky Mountain juniper is adapted to dry climates and requires only about 10 inches (254 mm) of annual precipitation [11,65]. The average annual precipitation in its range varies from 12 inches (305 mm) in the Southwest, Great Basin, and eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado to 26 inches (660 mm) in the Puget Sound area [90].

Tolerance/affinity for harsh environments: Rocky Mountain juniper is considered hardy except for "burning" of foliage on trees exposed to northwest winds during winter in the northern Great Plains [50]. It can tolerate shade when young, but becomes intolerant later in life [11,26,65]. It is more drought tolerant than eastern redcedar and less so than other tree junipers in the west [90]. In fact, during the 1930s drought, Rocky Mountain juniper woodland maintained and expanded range in the western Dakotas [107].

Elevation: Rocky Mountain juniper is found near sea level in the Puget Sound to 9,000 feet (2,700 m) in the Southwest [65,90]. Elevation ranges for Rocky Mountain juniper in some states are:

| Arizona | 5,000-9,000 feet (1,500-2,700 m) [65,74] |

| Colorado | 4,000-8,500 feet (1,200-2,600 m) [62,65] |

| Idaho | 2,000-5,000 feet (600-1,500 m) |

| Montana | 1,900-7,500 feet (600-2,300 m) |

| Nevada | 3,500-7,400 feet (1,000-2,000 m) [65] |

| New Mexico | 5,000-9,000 feet (1,500-2,800 m) [65,81] |

| Texas | 2,000-6,000 feet (600-1,800 m) [113] |

| Utah | 3,500-7,400 feet (1,100-2,300 m) [65] |

Additional Rocky Mountain juniper phenological data from an Arizona study are

[64]:

Bark begins to slip: 4/8

Pollen shedding and female flowers open: 4/15

Approximate start of leader elongation: 4/20

First conspicuous formation of male flowers: 8/26

Bark begins to stick: 9/15

Leader elongation ceases: 10/19

Fire regimes: Fire return intervals vary for habitats where Rocky Mountain juniper occurs. For example, in pinyon-juniper habitat (including Rocky Mountain juniper) of the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico, the mean fire interval was 28 years with a range of 10-49 years, and fires that covered more than 25 acres (10 hectares) occurred at 15-20 year intervals in other areas of New Mexico. Research in the Walnut Canyon National Monument in Arizona reported surface fire intervals of 20-30 years for pinyon-juniper habitat where Rocky Mountain juniper occurs [94].

A fire history study in Mesa Verde National Park estimated the historic interval between stand-replacing fires for pinyon-juniper habitat, where Rocky Mountain juniper was a dominant, at approximately 400 years, and large fires may have not occurred for more than 600 years in some areas. In contrast, fire intervals for chaparral communities in the park were estimated at 100 years. It appears that, in this area, pinyon-juniper habitat that was burned severely was replaced by chaparral species, which are more fire tolerant. As a result, pinyon-juniper habitat is found mostly in the southern part of the park, where cliffs and sparsely vegetated slopes form a barrier to fire. Though this habitat type may support heavy fuel loads, horizontal fuel continuity remains low, so crown fires are usually confined to relatively small areas unless high winds and extreme drought occur [47].

Little information was available regarding fire regimes specific to Rocky Mountain juniper communities as of 2002. Fire return intervlas for plant communities and ecosystems in which Rocky Mountain juniper occurs are summarized below. Find further fire regime information for the plant communities in which this species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under "Find Fire Regimes".

| Community or Ecosystem | Dominant Species | Fire Return Interval Range (years) |

| sagebrush steppe | Artemisia tridentata/Pseudoroegneria spicata | 20-70 [94] |

| basin big sagebrush | Artemisia tridentata var. tridentata | 12-43 [104] |

| mountain big sagebrush | Artemisia tridentata var. vaseyana | 15-40 [10,22,85] |

| Wyoming big sagebrush | Artemisia tridentata var. wyomingensis | 10-70 (40**) [124,131] |

| saltbush-greasewood | Atriplex confertifolia-Sarcobatus vermiculatus | < 35 to < 100 |

| desert grasslands | Bouteloua eriopoda and/or Pleuraphis mutica | 5-100 |

| plains grasslands | Bouteloua spp. | < 35 [94] |

| curlleaf mountain-mahogany* | Cercocarpus ledifolius | 13-1000 [13,106] |

| mountain-mahogany-Gambel oak scrub | Cercocarpus ledifolius-Quercus gambelii | < 35 to < 100 |

| western juniper | Juniperus occidentalis | 20-70 |

| Rocky Mountain juniper | Juniperus scopulorum | < 35 [94] |

| western larch | Larix occidentalis | 25-100 |

| blue spruce* | Picea pungens | 35-200 [9] |

| pinyon-juniper | Pinus-Juniperus spp. | < 35 [94] |

| whitebark pine* | Pinus albicaulis | 50-200 [9] |

| Rocky Mountain lodgepole pine* | Pinus contorta var. latifolia | 25-300+ [7,9,102] |

| Colorado pinyon | Pinus edulis | 10-49 [94] |

| interior ponderosa pine* | Pinus ponderosa var. scopulorum | 2-30 [9,15,79] |

| aspen-birch | Populus tremuloides-Betula papyrifera | 35-200 [33,126] |

| mountain grasslands | Pseudoroegneria spicata | 3-40 (10**) [7,9] |

| Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir* | Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca | 25-100 [9,10,12] |

| oak-juniper woodland (Southwest) | Quercus-Juniperus spp. | < 35 to < 200 [94] |

| Oregon white oak | Quercus garryana | < 35 [9] |

| bur oak | Quercus macrocarpa | < 10 [126] |

| oak savanna | Quercus macrocarpa/Andropogon gerardii-Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-14 [94,126] |

| elm-ash-cottonwood | Ulmus-Fraxinus-Populus spp. | < 35 to 200 [33,126] |

Fire is a major factor controlling the distribution of Rocky Mountain juniper [114,130]. Reduced fire frequency, along with climate change and introduction of grazing, accounts for the expansion of juniper woodlands into meadows, grasslands, sagebrush communities, and aspen groves that began in the late 1800s. Prior to this time, more frequent fires probably maintained low density in woodlands and often restricted junipers to rocky sites [86]. In general, the species grows in areas that do not burn frequently or intensely.

Frequent fires in the pinyon-juniper type can maintain a grassland setting, and the absence of fire will allow conversion to woodlands [54]. Wildfire eliminated Rocky Mountain juniper for 28 years in the Missouri, Judith, and Musselshell river breaks of central Montana [35]. In many areas where Rocky Mountain juniper grows, lack of heavy fuels may limit fire activity to surface fires of low intensity, allowing the species to persist [101]. It is often found in ponderosa pine forests where fire has been absent for long periods [93,101], and the resurgence of Rocky Mountain juniper in Idaho grasslands is due to fire cessation [75]. Severe fires in Douglas fir-Rocky Mountain juniper habitats in Montana appear limited to local areas where fire is carried into the crowns of widely-spaced trees [101].

After fire in pinyon-juniper habitat, junipers will usually invade the area first, followed by pinyon, which may eventually replace juniper on higher sites [69]. The following stages have been outlined for postfire succession in southwestern Colorado climax pinyon-juniper forest (including Rocky Mountain juniper): 1) skeleton forest and bare soil, 2) annual stage, 3) perennial grass-forb stage, 4) shrub stage, 5) shrub-open tree stage, 6) climax pinyon-juniper forest [38,94]. It takes approximately 300 years to reach climax [94].

Postfire succession in western Utah juniper

woodland (including Rocky Mountain juniper) takes approximately 85-90 years:

1) skeleton forest and bare soil,

2) annual stage,

3) perennial grass-forb stage,

4)perennial grass-forb-shrub stage,

5) perennial grass-forb-shrub-young juniper stage,

6) shrub-juniper stage, 7)

juniper woodland [38,94].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:

The Research Project Summary

Vegetation response to restoration treatments in ponderosa pine-Douglas-fir forests of western Montana

provides information on prescribed fire use and postfire response of plant community

species including Rocky Mountain juniper.

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Fire has long been recognized as a control mechanism for juniper [44]. In the 1950s and 1960s

some pinyon-juniper elimination operations were conducted by mechanical methods and slash was

piled and burned. Some areas where these large fuel loads were burned remained free of vegetation

20 years later [94].

In areas where Rocky Mountain juniper is not desirable, young trees have been killed mechanically by scorching the crown and stems [44]. Tree-by-tree burning and wildfire both control Rocky Mountain juniper effectively in juniper and sagebrush-grass types in Wyoming [45]. In central Oregon, one juniper control technique is to conduct prescribed fires several years after harvesting trees, when herbaceous vegetation will be present to provide fuel to carry fire to juniper seedlings [94]. In general, control of Rocky Mountain juniper by fire has been more effective in the southern part of its range [90].

Thinning undergrowth in pinyon-juniper woodlands favors Rocky Mountain juniper by reducing the number and intensity of fires and reducing competition for moisture [89].

Palatability/nutritional value: Waxwings are the principal consumers of Rocky Mountain juniper cones ("berries"), but numerous other birds and mammals include the berries in their diets [121]. Big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), bitterbrush (Purshia spp.), and Rocky Mountain juniper combined have been reported to make up 66% of winter mule deer browse [16] and Rocky Mountain juniper is considered a major component of wintering mule deer diet in the Bridger Mountains of Montana [54]. Mule deer browse the foliage moderately in winter, spring, and fall, and lightly in the summer [77]. High levels of volatile oils in Rocky Mountain juniper may cause mule deer to select against the foliage in favor of other browse when available [30]. Other animals that use Rocky Mountain juniper berries, foliage, or stems for forage include white-tailed deer, black-tailed deer, Rocky Mountain goats, ring-necked pheasant, grouse, and cattle [25,36,105,121]. Overall, it is rated good in energy value and fair in protein value [31].

Palatability of Rocky Mountain juniper is rated as follows [31]:

| CO | MT | ND | UT | WY | |

| cattle | poor | poor | ---- | poor | poor |

| domestic sheep | poor | poor | poor | fair | fair |

| horses | poor | poor | poor | poor | poor |

| antelope | ---- | ---- | poor | poor | poor |

| elk | poor | poor | ---- | fair | fair |

| mule deer | poor | poor | fair | fair | good |

| white-tailed deer | ---- | ---- | poor | ---- | good |

| small mammals | good | poor | ---- | good | good |

| small nongame birds | ---- | poor | fair | good | good |

| upland game birds | ---- | poor | good | good | fair |

| waterfowl | ---- | ---- | ---- | poor | poor |

Relative food and cover values of Rocky Mountain juniper for white-tailed deer and mule deer in Wyoming are as follows [91,92]:

| summer forage | winter forage | hiding/escape cover | thermal cover | fawning cover | |

| white-tailed deer | fair | good | excellent | excellent | good |

| mule deer | poor | fair | excellent | excellent | good |

Cover value: The dense protective shelter of Rocky Mountain juniper is especially valuable in the winter [121].

Rocky Mountain juniper woodlands provide nesting habitat, migratory corridors, and winter food and cover for birds otherwise found only in forested areas and provide needed woody cover for birds on the edges of grasslands [111]. Rocky Mountain juniper is a favored nesting tree of chipping sparrows, robins, song sparrows, and mockingbirds [121], and is used for nesting by sharp-shinned hawks in Utah [96]. Juncos, myrtle warblers, sparrows and other birds roost in the dense foliage [121].

In the northern Great Plains Rocky Mountain juniper woodlands provide habitat for bushy-tailed woodrats, white-footed mice, deer mice, prairie voles, pocket mice, and eastern cottontail [103,110]. Big game use the Rocky Mountain juniper habitat type for forage and cover [56,60].

Cover value of Rocky Mountain juniper is rated as follows [31]:

| CO | MT | ND | UT | WY | |

| pronghorn | ---- | ---- | poor | poor | poor |

| elk | fair | good | ---- | fair | good |

| mule deer | good | good | good | good | good |

| white-tailed deer | ---- | ---- | good | ---- | good |

| small mammals | good | fair | fair | good | good |

| small nongame birds | good | fair | good | good | good |

| upland game birds | ---- | fair | fair | good | good |

| waterfowl | ---- | ---- | ---- | good | good |

| antelope | ---- | ---- | poor | poor | poor |

Native Americans have used Rocky Mountain juniper seeds, "berries", and foliage for

incense, teas, or salves to treat a variety of ailments including respiratory problems, backaches,

vomiting and diarrhea, dandruff, high fever, arthritis and muscular aches, kidney and urinary

ailments, and heart and circulatory problems. It has also been used to facilitate childbirth

[24,37,63,120,121]. Juniper berries are also used to make gin [11].

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Propagation:

Rocky Mountain juniper can be propagated from cuttings

or from seed [18], though it can be difficult to grow from seed due to

prolonged dormancy [99]. Trickle irrigation of wooded draws in coal-mine spoils of

the Northern High Plains increased the survival rate of Rocky Mountain juniper by

nearly 100% [18]. Wagner and others [127], Noble [90], and U.S.D.A. [121] discuss methods of artificial regeneration of Rocky

Mountain juniper.

Pests: Rocky Mountain juniper is hearty and relatively disease resistant and insect tolerant [123]. However, several cedar foliage rusts are found on Rocky Mountain juniper. Cedar apple blight (Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae), for which Rocky Mountain juniper is the alternate host, does little harm [65,121]. Two similar rusts (G. betheli and G. nelsoni) cause galls on stems. The extent of damage in the wild is unknown, but these rusts can be destructive to nursery stock. Juniper mistletoes are also found on Rocky Mountain juniper in Arizona and New Mexico, but their effects are unknown [65]. Other diseases to which the tree is susceptible include Phomopsis blight (Phomopsis juniperovora), Cercospora blight (Cercospora sequoiae var. juniperi), and Kabatina tip blight (Kabatina juniperi) [65,100].

Rocky Mountain juniper is also vulnerable to attack by several insects, including the following: roundheaded borer (Callidium californicum) in Oregon and Washington, bark beetles (Phloeosinus scopulorum) in Washington and British Columbia, cedar twig beetles (Phloeosinus spp.) throughout the central and southern part of its range, cedar flathead borers (Chrysobothris spp.), and gall midges (Walshomyia insignis) [65]. Two species of spider mites and 2 species of juniper berry mites can also cause problems. Noble [90] discusses pests and their effects in more detail.

Control: Rocky Mountain juniper is difficult to kill without cutting or fire, though herbicides may work to kill individual trees [90]. A combination of tebuthiuron and picloram was somewhat effective at controlling Rocky Mountain juniper in pinyon-juniper woodlands of New Mexico; the effectiveness of both decreased as the size of trees increased [83]. A 2-way application of Tordon did not significantly affect Rocky Mountain juniper [45]. Refer to Fire Effects for information on using fire to control Rocky Mountain juniper.

Other: Rocky Mountain juniper is susceptible to erosion damage because the species establishes on exposed, erodable sites [65,111]. Use by animals as "rubbing posts" may also damage stems and roots, and may provide an entryway for pathogens. Also, range animals may browse, or "high-line", crown foliage and alter growth and vigor of trees [90]. In wet years and near springs, use by American bison and cattle should be monitored to avoid accelerating the erosion process by overuse [111].

1. Adams, Robert P. 1982. The effects of gases from a burning coal seam on morphological and terpenoid characters in Juniperus scopulorum (Cupressaceae). The Southwestern Naturalist. 27(3): 279-286. [293]

2. Alexander, Robert R. 1985. Major habitat types, community types and plant communities in the Rocky Mountains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-123. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 105 p. [303]

3. Alexander, Robert R. 1986. Classification of the forest vegetation of Wyoming. Res. Note RM-466. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 10 p. [304]

4. Alexander, Robert R. 1987. Classification of the forest vegetation of Colorado by habitat type and community type. Res. Note RM-478. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 14 p. [9092]

5. Alexander, Robert R. 1988. Forest vegetation on National Forests in the Rocky Mountain and Intermountain Regions: habitat and community types. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-162. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 47 p. [5903]

6. Alexander, Robert R.; Hoffman, George R.; Wirsing, John M. 1986. Forest vegetation of the Medicine Bow National Forest in southeastern Wyoming: a habitat type classification. Res. Pap. RM-271. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 39 p. [307]

7. Arno, Stephen F. 1980. Forest fire history in the Northern Rockies. Journal of Forestry. 78(8): 460-465. [11990]

8. Arno, Stephen F. 1991. Ecological relationships of interior Douglas-fir. In: Baumgartner, David M.; Lotan, James E., compilers. Interior Douglas-fir: The species and its management: Symposium proceedings; 1990 February 27 - March 1; Spokane, WA. Pullman, WA: Washington State University, Cooperative Extension: 47-51. [18271]

9. Arno, Stephen F. 2000. Fire in western forest ecosystems. In: Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler, eds. Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 97-120. [36984]

10. Arno, Stephen F.; Gruell, George E. 1983. Fire history at the forest-grassland ecotone in southwestern Montana. Journal of Range Management. 36(3): 332-336. [342]

11. Arno, Stephen F.; Hammerly, Ramona P. 1977. Northwest trees. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers. 222 p. [4208]

12. Arno, Stephen F.; Scott, Joe H.; Hartwell, Michael G. 1995. Age-class structure of old growth ponderosa pine/Douglas-fir stands and its relationship to fire history. Res. Pap. INT-RP-481. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 25 p. [25928]

13. Arno, Stephen F.; Wilson, Andrew E. 1986. Dating past fires in curlleaf mountain-mahogany communities. Journal of Range Management. 39(3): 241-243. [350]

14. Aro, Richard S. 1971. Evaluation of pinyon-juniper conversion to grassland. Journal of Range Management. 24(2): 188-197. [355]

15. Baisan, Christopher H.; Swetnam, Thomas W. 1990. Fire history on a desert mountain range: Rincon Mountain Wilderness, Arizona, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 20: 1559-1569. [14986]

16. Bayless, Steve. 1971. Relationships between big game and sagebrush. Paper presented at: Annual meeting of the Northwest Section of the Wildlife Society; 1971 March 25-26; Bozeman, MT. 14 p. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17098]

17. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p. [434]

18. Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1986. Wooded draws of the northern high plains: characteristics, value and restoration (North and South Dakota). Restoration & Management Notes. 4(2): 74-75. [4226]

19. Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Girard, Michele. 1984. Wooded draws in rangelands of the northern Great Plains. In: Henderson, F. R., ed. Guidelines for increasing wildlife on farms and ranches: With ideas for supplemental income sources for rural families. Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University, Cooperative Extension Service; Great Plains Agricultural Council, Wildlife Resources Committee: 27B-36B. [4239]

20. Boccard, Bruce. 1980. Important fish and wildlife habitats of Idaho. An inventory. Boise, ID: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon- Idaho Area Office. 161 p. [18109]

21. Brown, David E. 1982. Great Basin conifer woodland. In: Brown, David E., ed. Biotic communities of the American Southwest--United States and Mexico. Desert Plants. 4(1-4): 52-57. [535]

22. Burkhardt, Wayne J.; Tisdale, E. W. 1976. Causes of juniper invasion in southwestern Idaho. Ecology. 57: 472-484. [565]

23. Carty, Dave. 1996. The drought busters. American Forests. 102(2): 33, 36-38. [27171]

24. Castetter, Edward F. 1935. Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest. Biological Series No.4: Volume 1. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico. 62 p. [35938]

25. Cowan, Ian McTaggart. 1945. The ecological relationships of the food of the Columbian black-tailed deer, Odocoileus hemionus columbianus (Richardson), in the coast forest region of southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Ecological Monographs. 15(2): 110-139. [16006]

26. Crane, Marilyn F. 1982. Fire ecology of Rocky Mountain Region forest habitat types. Final report: Contract No. 43-83X9-1-884. Missoula, MT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Region 1. 272 p. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [5292]

27. Cronquist, Arthur; Holmgren, Arthur H.; Holmgren, Noel H.; Reveal, James L. 1972. Intermountain flora: Vascular plants of the Intermountain West, U.S.A. Vol. 1. New York: Hafner Publishing Company, Inc. 270 p. [717]

28. Cunningham, Richard A. 1975. Provisional tree and shrub seed zones for the Great Plains. Res. Pap. RM-150. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 15 p. [4516]

29. Davis, Kathleen M.; Clayton, Bruce D.; Fischer, William C. 1980. Fire ecology of Lolo National Forest habitat types. INT-79. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 77 p. [5296]

30. Dietz, Donald R.; Nagy, Julius G. 1976. Mule deer nutrition and plant utilization. In: Workman, Gar W.; Low, Jessop B., eds. Mule deer decline in the West: A symposium; [1976]

31. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The plant information network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

32. Dixon, Helen. 1935. Ecological studies on the high plateaus of Utah. Botanical Gazette. 97: 272-320. [15672]

33. Duchesne, Luc C.; Hawkes, Brad C. 2000. Fire in northern ecosystems. In: Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler, eds. Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 35-51. [36982]

34. Dusek, Gary L.; Wood, Alan K.; Mackie, Richard J. 1988. Habitat use by white-tailed deer in prairie-agricultural habitat in Montana. Prairie Naturalist. 20(3): 135-142. [6801]

35. Eichhorn, Larry C.; Watts, C. Robert. 1984. Plant succession on burns in the river breaks of central Montana. Proceedings, Montana Academy of Science. 43: 21-34. [15478]

36. Ellison, Laurence. 1966. Seasonal foods and chemical analysis of winter diet of Alaskan spruce grouse. Journal of Wildlife Management. 30(4): 729-735. [9735]

37. Elmore, Francis H. 1944. Ethnobotany of the Navajo. Monograph Series: Vol 1, Number 7. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico. 136 p. [35897]

38. Evans, Raymond A. 1988. Management of pinyon-juniper woodlands. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-249. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 34 p. [4541]

39. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

40. Fassett, Norman C. 1944. Juniperus virginiana, J. horizontalis and J. scopulorum. 2. Hybrid swarms of J. virginiana and J. scopolarum. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 71(5): 475-483. [4007]

41. Fassett, Norman C. 1944. Juniperus virginiana, J. horizontalis and J. scoulorum. 1. The specific characters. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 71(4): 410-418. [910]

42. Fassett, Norman C. 1945. Juniperus virginiana, J. horizontalis, and J. scopulorum. 5. Taxonomic treatment. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 72(5): 480-482. [912]

43. Ffolliott, Peter F. 1999. Woodland and scrub formations in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. In: Ffolliott, Peter F.; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo, eds. Ecology and management of forests, woodlands, and shrublands in the dryland regions of the United States and Mexico: perspectives for the 21st century. Co-edition No. 1. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona; La Paz, Mexico: Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste, SC; Flagstaff, AZ: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 23-37. [37043]

44. Fischer, William C.; Clayton, Bruce D. 1983. Fire ecology of Montana forest habitat types east of the Continental Divide. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-141. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 83 p. [923]

45. Fisser, Herbert G. 1981. Shrub establishment, dominance, and ecology on the juniper and sagebrush-grass types in Wyoming. In: Shrub establishment on disturbed arid and semi-arid lands: Proceedings of the symposium; 1980 December 2-3; Laramie, WY. Laramie, WY: Wyoming Game and Fish Department: 23-28. [926]

46. Flora of North America Association. 2000. Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 2: Pteridophytes and gymnosperms, [Online]. Available: http://hua.huh.harvard.edu/FNA/ [2002, March 27]. [36990]

47. Floyd, M. Lisa; Romme, William H.; Hanna, David D. 2000. Fire history and vegetation pattern in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, USA. Ecological Applications. 10(6): 1666-1680. [37590]

48. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others]. 1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

49. Gartner, F. R. 1986. The many faces of South Dakota rangelands: description and classification. In: Clambey, Gary K.; Pemble, Richard H., eds. The prairie: past, present and future: Proceedings, 9th North American prairie conference; 1984 July 29 - August 1; Moorhead, MN. Fargo, ND: Tri-College University Center for Environmental Studies: 81-85. [3529]

50. George, Ernest J. 1953. Tree and shrub species for the Northern Great Plains. Circular No. 912. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. 46 p. [4566]

51. Gottfried, Gerald J. 1992. Ecology and management of the southwestern pinyon-juniper woodlands. In: Ffolliott, Peter F.; Gottfried, Gerald J.; Bennett, Duane A.; [and others], technical coordinators. Ecology and management of oaks and associated woodlands: perspectives in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico: Proceedings; 1992 April 27-30; Sierra Vista, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-218. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 78-86. [19745]

52. Gottfried, Gerald J. 1999. Pinyon-juniper woodlands in the southwestern United States. In: Ffolliott, Peter F.; Ortega-Rubio, Alfredo, eds. Ecology and management of forests, woodlands, and shrublands in the dryland regions of the United States and Mexico: perspectives for the 21st century. Co-edition No. 1. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona; La Paz, Mexico: Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas del Noroeste, SC; Flagstaff, AZ: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 53-67. [37045]

53. Great Plains Flora Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1392 p. [1603]

54. Gruell, George E. 1986. Post-1900 mule deer irruptions in the Intermountain West: principle cause and influences. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-206. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 37 p. [1049]

55. Hall, Marion T. 1961. Notes on cultivated junipers. Butler University Botanical Studies. 14: 73-90. [19796]

56. Hansen, Paul L.; Chadde, Steve W.; Pfister, Robert D. 1988. Riparian dominance types of Montana. Misc. Publ. No. 49. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station. 411 p. [5660]

57. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R. 1988. The vegetation of the Grand River/Cedar River, Sioux, and Ashland Districts of the Custer National Forest: a habitat type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-157. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 68 p. [771]

58. Hansen, Paul L.; Hoffman, George R.; Bjugstad, Ardell J. 1984. The vegetation of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota: a habitat type classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-113. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 35 p. [1077]

59. Hansen, Paul L.; Pfister, Robert D.; Boggs, Keith; [and others]. 1995. Classification and management of Montana's riparian and wetland sites. Miscellaneous Publication No. 54. Missoula, MT: The University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station. 646 p. [24768]

60. Hansen, Paul; Boggs, Keith; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John. 1990. Classification and management of riparian and wetland sites in central and eastern Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station, Montana Riparian Association. 279 p. [12477]

61. Hansen, Paul; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John; [and others]. 1989. Classification and management of riparian sites in southwestern Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry, Montana Riparian Association. 292 p. Draft Version 2. [8900]

62. Harrington, H. D. 1964. Manual of the plants of Colorado. 2d ed. Chicago: The Swallow Press, Inc. 666 p. [6851]

63. Hart, Jeffrey A. 1981. The ethnobotany of the northern Cheyenne Indians of Montana. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 4: 1-55. [35893]

64. Herman, F. R. 1956. Growth and phenological observations of Arizona junipers. Ecology. 37: 193-195. [4117]

65. Herman, F. R. 1958. Silvical characteristics of Rocky Mountain juniper. Station Paper No. 29. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 20 p. [16920]

66. Hess, Karl; Alexander, Robert R. 1986. Forest vegetation of the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests in central Colorado: a habitat type classification. Res. Pap. RM-266. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 48 p. [1141]

67. Hitchcock, C. Leo; Cronquist, Arthur. 1973. Flora of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. 730 p. [1168]

68. Hoffman, George R.; Alexander, Robert R. 1987. Forest vegetation of the Black Hills National Forest of South Dakota and Wyoming: a habitat type classification. Res. Pap. RM-276. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 48 p. [1181]

69. Holland, Carol J. 1990. Pinyon-juniper management in Region 3. In: Silvicultural challenges and opportunities in the 1990's: Proceedings of the National Silvicultural Workshop; 1989 July 10-13; Petersburg, AK. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Timber Management: 206-216. [15032]

70. Jankovsky-Jones, Mabel; Rust, Steven K.; Moseley, Robert K. 1999. Riparian reference areas in Idaho: a catalog of plant associations and conservation sites. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-20. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 141 p. [29900]

71. Johnson, Alan R.; Milne, Bruce T.; Hraber, Peter. 1996. Analysis of change in pinon-juniper woodlands based on aerial photography, 1930's-1980's. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico, Department of Biology; Final report to the USDA Forest Service. Cooperative Agreement No. 28-C4-860. 12 + p. [27714]

72. Johnson, Carl M. 1970. Common native trees of Utah. Special Report 22. Logan, UT: Utah State University, College of Natural Resources, Agricultural Experiment Station. 109 p. [9785]

73. Kartesz, John T.; Meacham, Christopher A. 1999. Synthesis of the North American flora (Windows Version 1.0), [CD-ROM]. Available: North Carolina Botanical Garden. In cooperation with the Nature Conservancy, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [2001, January 16]. [36715]

74. Kearney, Thomas H.; Peebles, Robert H.; Howell, John Thomas; McClintock, Elizabeth. 1960. Arizona flora. 2d ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. 1085 p. [6563]

75. Kucera, Clair L. 1981. Grasslands and fire. In: Mooney, H. A.; Bonnicksen, T. M.; Christensen, N. L.; [and others], technical coordinators. Fire regimes and ecosystem properties: Proceedings of the conference; 1978 December 11-15; Honolulu, HI. Gen. Tech. Rep. WO-26. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 90-111. [4389]

76. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. United States [Potential natural vegetation of the conterminous United States]. Special Publication No. 36. New York: American Geographical Society. 1:3,168,000; colored. [3455]

77. Kufeld, Roland C.; Wallmo, O. C.; Feddema, Charles. 1973. Foods of the Rocky Mountain mule deer. Res. Pap. RM-111. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 31 p. [1387]

78. Lanner, Ronald M. 1983. Trees of the Great Basin: A natural history. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. 215 p. [1401]

79. Laven, R. D.; Omi, P. N.; Wyant, J. G.; Pinkerton, A. S. 1980. Interpretation of fire scar data from a ponderosa pine ecosystem in the central Rocky Mountains, Colorado. In: Stokes, Marvin A.; Dieterich, John H., technical coordinators. Proceedings of the fire history workshop; 1980 October 20-24; Tucson, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-81. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 46-49. [7183]

80. Lymbery, Gordon A.; Pieper, Rex D. 1983. Ecology of pinyon-juniper vegetation in the northern Sacramento Mountains. Bulletin 698. Las Cruces, NM: New Mexico State University, Agricultural Experiment Station. 48 p. [4484]

81. Martin, William C.; Hutchins, Charles R. 1981. A flora of New Mexico. Volume 2. Germany: J. Cramer. 2589 p. [37175]

82. McCaughey, Ward W.; Schmidt, Wyman C.; Shearer, Raymond C. 1986. Seed-dispersal characteristics of conifers. In: Shearer, Raymond C., compiler. Proceedings--conifer tree seed in the Inland Mountain West symposium; 1985 August 5-6; Missoula, MT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-203. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 50-62. [12593]

83. McDaniel, Kirk C.; WhiteTrifaro, Linda. 1987. Selective control of pinyon-juniper with herbicides. In: Everett, Richard L., compiler. Proceedings--pinyon-juniper conference; 1986 January 13-16; Reno, NV. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-215. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 448-455. [29495]

84. Meeuwig, Richard O.; Bassett, Richard L. 1983. Pinyon-juniper. In: Burns, Russell M., compiler. Silvicultural systems for the major forest types of the United States. Agriculture Handbook No. 445. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 84-86. [3899]

85. Miller, Richard F.; Rose, Jeffery A. 1995. Historic expansion of Juniperus occidentalis (western juniper) in southeastern Oregon. The Great Basin Naturalist. 55(1): 37-45. [26637]

86. Miller, Richard F.; Wigand, Peter E. 1994. Holocene changes in semiarid pinyon-juniper woodlands. Bioscience. 44(7): 465-474. [23563]

87. Mitchell, Jerry M. 1984. Fire management action plan: Zion National Park, Utah. Record of Decision. 73 p. Salt Lake City, UT: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. [17278]

88. Montana State University, Montana Agricultural Experiment Station. 1973. Vegetative rangeland types in Montana. Bulletin 671. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University, Montana Agricultural Experiment Station. 15 p. [29827]

89. Mueggler, Walter F. 1976. Ecological role of fire in western woodland and range ecosystems. In: Use of prescribed burning in western woodland and range ecosystems: Proceedings of the symposium; 1976 March 18-19; Logan, UT. Logan, UT: Utah State University, Utah Agricultural Experiment Station: 1-9. [1709]

90. Noble, Daniel L. 1990. Juniperus scopulorum Sarg. Rocky Mountain juniper. In: Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H., technical coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 1. Conifers. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 116-126. [13376]

91. Olson, Rich. 1992. Mule deer habitat requirements and management in Wyoming. B-965. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, Cooperative Extension Service. 15 p. [20679]

92. Olson, Rich. 1992. White-tailed deer habitat requirements and management in Wyoming. B-964. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, Cooperative Extension Service. 17 p. [20678]

93. Oswald, Brian P.; Balice, Randy G.; Scott, Kelly B. 2000. Fuel loads and overstory conditions at Los Alamos National Laboratory, New Mexico. In: Moser, W. Keith; Moser, Cynthia F., eds. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture and vegetation management: Proceedings of the 21st Tall Timbers fire ecology conference: an international symposium; 1998 April 14-16; Tallahassee, FL. No. 21. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research, Inc: 41-45. [37609]

94. Paysen, Timothy E.; Ansley, R. James; Brown, James K.; [and others]. 2000. Fire in western shrubland, woodland, and grassland ecosystems. In: Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler, eds. Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-volume 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 121-159. [36978]

95. Pieper, Rex D. 1977. The southwestern pinyon-juniper ecosystem. In: Aldon, Earl F.; Loring, Thomas J., technical coordinators. Ecology, uses, and management of pinyon-juniper woodlands: Proceedings of the workshop; 1977 March 24-25; Albuquerque, NM. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-39. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 1-6. [17251]

96. Platt, Joseph B. 1976. Sharp-shinned hawk nesting and nest site selection in Utah. The Condor. 78(1): 102-103. [23781]

97. Probart, Judy. 1992. Limber pine is first in its class. Intermountain Reporter. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Region. June/July: 14-15. [21597]

98. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

99. Rietveld, W. J. 1989. Variable seed dormancy in Rocky Mountain juniper. In: Landis, Thomas D., technical coordinator. Proceedings: Intermountain Forest Nursery Association; 1989 August 14-18; Bismarck, ND. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-184. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 60-64. [11528]

100. Riffle, Jerry W.; Peterson, Glenn W., technical coordinators. 1986. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-129. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 149 p. [16990]

101. Roberts, David W.; Sibbernsen, John I. 1979. Forest and woodland habitat types of north central Montana. Volume 2: The Missouri River Breaks. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry. In cooperation with: Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory. 24 p. [2001]

102. Romme, William H. 1982. Fire and landscape diversity in subalpine forests of Yellowstone National Park. Ecological Monographs. 52(2): 199-221. [9696]

103. Rumble, Mark A.; Gobeille; John E. 1995. Wildlife associations in Rocky Mountain juniper in the Northern Great Plains, South Dakota. In: Shaw, Douglas W.; Aldon, Earl F.; LoSapio, Carol, technical coordinators. Desired future conditions for pinon-juniper ecosystems: Proceedings of the symposium; 1994 August 8-12; Flagstaff, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-258. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 80-90. [24800]

104. Sapsis, David B. 1990. Ecological effects of spring and fall prescribed burning on basin big sagebrush/Idaho fescue--bluebunch wheatgrass communities. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University. 105 p. Thesis. [16579]

105. Saunders, Jack K., Jr. 1955. Food habits and range use of the Rocky Mountain goat in the Crazy Mountains, Montana. Journal of Wildlife Management. 19(4): 429-437. [484]

106. Schultz, Brad W. 1987. Ecology of curlleaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) in western and central Nevada: population structure and dynamics. Reno, NV: University of Nevada. 111 p. Thesis. [7064]

107. Severson, Kieth E.; Boldt, Charles E. 1978. Cattle, wildlife, and riparian habitats in the western Dakotas. In: Management and use of northern plains rangeland: Regional rangeland symposium: Proceedings; 1978 February 27-28; Bismarck, ND. Dickinson, ND: North Dakota State University: 90-103. [65]

108. Shiflet, Thomas N., ed. 1994. Rangeland cover types of the United States. Denver, CO: Society for Range Management. 152 p. [23362]

109. Short, Henry L.; McCulloch, Clay Y. 1977. Managing pinyon-juniper ranges for wildlife. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-47. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 10 p. [2137]

110. Sieg, Carolyn Hull. 1988. The value of Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) woodlands in South Dakota as small mammal habitat. In: Szaro, Robert C.; Severson, Kieth E.; Patton, David R., technical coordinators. Management of amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals in North America: Proceedings of the symposium; 1988 July 19-21; Flagstaff, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-166. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 328-332. [7121]

111. Sieg, Carolyn Hull. 1991. Rocky Mountain juniper woodlands: year-round avian habitat. Res. Pap. RM-296. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 7 p. [16110]

112. Sieg, Carolyn Hull. 1997. The role of fire in managing for biological diversity on native rangelands of the Northern Great Plains. In: Uresk, Daniel W.; Schenbeck, Greg L.; O'Rourke, James T., tech. coords. Conserving biodiversity on native rangelands: symposium proceedings; 1995 August 17; Fort Robinson State Park, NE. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-GTR-298. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 31-38. [28054]

113. Simpson, Benny J. 1988. A field guide to Texas trees. Austin, TX: Texas Monthly Press. 372 p. [11708]

114. Stanton, Frank. 1974. Wildlife guidelines for range fire rehabilitation. Tech. Note 6712. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 90 p. [2221]

115. Steele, Robert; Cooper, Stephen V.; Ondov, David M.; [and others]. 1983. Forest habitat types of eastern Idaho-western Wyoming. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-144. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 122 p. [2230]

116. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT. 10 p. [20090]

117. Thilenius, John F. 1972. Classification of deer habitat in the ponderosa pine forest of the Black Hills, South Dakota. Res. Pap. RM-91. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 28 p. [2317]

118. Tiedeman, James A.; Francis, Richard E.; Terwilliger, Charles, Jr.; Carpenter, Len H. 1987. Shrub-steppe habitat types of Middle Park, Colorado. Res. Pap. RM-273. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 20 p. [2329]

119. Tueller, Paul T.; Clark, James E. 1975. Autecology of pinyon-juniper species of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. In: The pinyon-juniper ecosystem: a symposium: Proceedings; 1975 May; Logan, UT. Logan, UT: Utah State University, College of Natural Resources, Utah Agricultural Experiment Station: 27-40. [2368]

120. Turner, Nancy J. 1988. Ethnobotany of coniferous trees in Thompson and Lillooet Interior Salish of British Columbia. Economic Botany. 42(2): 177-194. [4542]

121. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Resource Conservation Service. 2003. PLANTS database (2003), [Online]. Available: https://plants.usda.gov /. [34262]

122. Van Haverbeke, David F. 1980. Rocky Mountain juniper. In: Eyre, F.H., ed. Cover Types of the United States and Canada. Washington, D.C., Society of American Foresters: 99-100. [2422]

123. Van Haverbeke, David F.; King, Rudy M. 1990. Genetic variation in Great Plains Juniperus. Res. Pap. RM-292. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 8 p. [13637]

124. Vincent, Dwain W. 1992. The sagebrush/grasslands of the upper Rio Puerco area, New Mexico. Rangelands. 14(5): 268-271. [19698]

125. Vogel, Willis G. 1981. A guide for revegetating coal minesoils in the eastern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-68. Broomall, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station. 190 p. [15575]

126. Wade, Dale D.; Brock, Brent L.; Brose, Patrick H.; [and others]. 2000. Fire in eastern ecosystems. In: Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler, eds. Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 53-96. [36983]

127. Wagner, A. M.; Harrington, J. T.; Mexal, J. G.; Fisher, J. T. 1992. Rooting of juniper in outdoor nursery beds. In: Landis, Thomas D., technical coordinator. Proceedings, Intermountain Forest Nursery Association; 1991 August 12-16; Park City, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-211. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 120-123. [20933]

128. West, Neil E.; Tausch, Robin J.; Tueller, Paul T. 1998. A management-oriented classification of pinyon-juniper woodlands of the Great Basin. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-12. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 42 p. [29131]

129. Wilke, Philip J. 1988. Bow staves harvested from juniper trees by Indians of Nevada. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 10(1): 3-31. [10870]

130. Wright, Henry A. 1972. Shrub response to fire. In: McKell, Cyrus M.; Blaisdell, James P.; Goodin, Joe R., eds. Wildland shrubs--their biology and utilization: Proceedings of a symposium; 1971 July; Logan, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 204-217. [2611]

131. Young, James A.; Evans, Raymond A. 1981. Demography and fire history of a western juniper stand. Journal of Range Management. 34(6): 501-505. [2659]

132. Zarn, Mark. 1977. Ecological characteristics of pinyon-juniper woodlands on the Colorado Plateau: A literature survey. Tech. Note T/N 310. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Denver Service Center. 183 p. [2689]