Index of Species Information

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

|

|

|

| Bluejoint. Image by Rob Routledge, Sault College, Bugwood.org. |

Introductory

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION:

Tesky, Julie L. 1992. Calamagrostis canadensis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station,

Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/graminoid/calcan/all.html [].

Revisions:

The taxonomy of this species was updated on 19 September 2018. Images were also added.

ABBREVIATION:

CALCAN

SYNONYMS:

For Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis (Michx.) Beauv.:

Calamagrostis canadensis var. imberbis (Stebbins) C.Hitchc.

Calamagrostis canadensis var. pallida (Vasey & Scriber) Stebbins

Calamagrostis canadensis var. robusta Vasey

Calamagrostis canadensis var. typica Stebbins [1,12,21,23,39]

For Calamagrostis canadensis var. langsdorffi (Link) Inman:

Calamagrostis canadensis (Michx.) P. Beauv. subsp. langsdorffii (Link) Hultén

Calamagrostis canadensis var. lactea (W.J. Beal.) C.Hitchc.

Calamagrostis canadensis var. scabra (J.Presl.) A.Hitchc. [1,12,21,23,39]

Calamagrostis canadensis var. macouniana (Vasey) Stebbins:

Calamagrostis macouniana (Vasey) Vasey [39]

NRCS PLANT CODE:

CACA4

COMMON NAMES:

bluejoint

bluejoint reedgrass

meadow pinegrass

Canadian reedgrass

marsh pinegrass

marsh reedgrass

Macoun's reedgrass

TAXONOMY:

The scientific name of bluejoint is Calamagrostis canadensis (Michx.)

Beauv. (Poaceae). Recognized varieties are as follows [1,12,21,23,39]:

Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis (Michx.) Beauv., bluejoint

Calamagrostis canadensis var. langsdorfii (Link) Inman, bluejoint

Calamagrostis canadensis var. macouniana (Vasey) Stebbins, Macoun's reedgrass

LIFE FORM:

Graminoid

FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS:

No special status

OTHER STATUS:

NO-ENTRY

DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

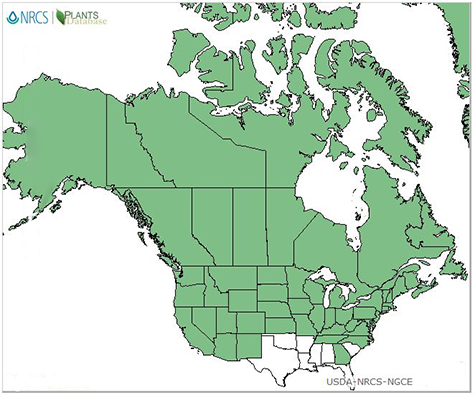

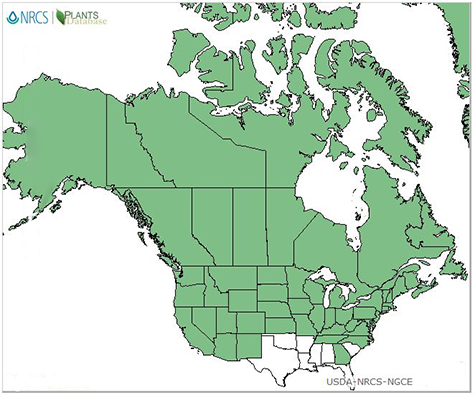

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION:

Bluejoint is the most common and widespread Calamagrostis

species in North America [38]. It occurs throughout the boreal and

temperate regions. Bluejoint is common in the subarctic from

Alaska to Quebec, and extends south to all but the southeastern United

States [16,17,38].

|

| Distribution of bluejoint. Map courtesy of USDA, NRCS. 2018. The PLANTS Database.

National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. [2018, September 19] [39]. |

ECOSYSTEMS:

FRES11 Spruce - fir

FRES19 Aspen - birch

FRES20 Douglas-fir

FRES21 Ponderosa pine

FRES22 Western white pine

FRES23 Fir - spruce

FRES25 Larch

FRES26 Lodgepole pine

FRES28 Western hardwoods

FRES34 Chaparral - mountain shrub

FRES35 Pinyon - juniper

FRES36 Mountain grasslands

FRES37 Mountain meadows

FRES38 Plains grasslands

FRES39 Prairie

FRES41 Wet grasslands

FRES44 Alpine

STATES:

AK AZ CA CO CT DE HI ID IL IN

IA KS KY ME MD MA MI MN MO MT

NE NV NH NJ NM NY NC ND OH OR

PA RI SD TN UT VA VT WA WV WI

WY AB BC LB MB NB NF NT NS ON

PE PQ SK YT

BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS:

1 Northern Pacific Border

2 Cascade Mountains

3 Southern Pacific Border

4 Sierra Mountains

5 Columbia Plateau

6 Upper Basin and Range

7 Lower Basin and Range

8 Northern Rocky Mountains

9 Middle Rocky Mountains

10 Wyoming Basin

11 Southern Rocky Mountains

12 Colorado Plateau

13 Rocky Mountain Piedmont

14 Great Plains

15 Black Hills Uplift

16 Upper Missouri Basin and Broken Lands

KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS:

K005 Mixed conifer forest

K007 Red fir forest

K008 Lodgepole pine - subalpine forest

K010 Ponderosa shrub - forest

K011 Western ponderosa pine

K012 Douglas-fir forest

K014 Grand fir - Douglas-fir forest

K015 Western spruce - fir forest

K016 Eastern ponderosa forest

K017 Black Hills pine forest

K018 Pine - Douglas-fir forest

K021 Southwestern spruce - fir forest

K023 Juniper - pinyon woodland

K030 California oakwoods

K033 Chaparral

K034 Montane chaparral

K037 Mountain mahogany - oak scrub

K038 Great Basin sagebrush

K049 Tules marshes

K052 Alpine meadows and barren

K055 Sagebrush steppe

K056 Wheatgrass - needlegrass shrubsteppe

K063 Foothills prairie

K064 Grama - needlegrass - wheatgrass

K065 Grama - buffalograss

K066 Wheatgrass - needlegrass

K067 Wheatgrass - bluestem - needlestem

K068 Wheatgrass - grama - buffalograss

K069 Bluestem - grama prairie

K074 Bluestem prairie

K081 Oak savanna

K093 Great Lakes spruce - fir forest

K094 Conifer bog

K096 Northeastern spruce - fir forest

K098 Northern floodplain forest

K104 Appalacian oak forest

K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest

SAF COVER TYPES:

12 Black spruce

13 Black spruce - tamarack

16 Aspen

18 Paper birch

21 Eastern white pine

22 White pine - hemlock

37 Paper birch - red spruce - balsam fir

38 Tamarack

68 Mesquite

107 White spruce

201 White spruce

202 White spruce - paper birch

204 Black spruce

206 Engelmann spruce - subalpine fir

208 Whitebark pine

212 Western Larch

215 Western white pine

217 Aspen

218 Lodgepole pine

243 Sierra Nevada mixed conifer

246 California black oak

250 Blue oak - gray pine

251 White spruce - aspen

252 Paper birch

253 Black spruce - white spruce

254 Black spruce - paper birch

255 California coast live oak

256 California mixed subalpine

SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES:

NO-ENTRY

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES:

Bluejoint occurs as an understory dominant or codominant in

many early seral to climax riparian and cool, moist forest communities.

Published classifications listing bluejoint as a dominant or

codominant in habitat types (hts), dominance types (dts), community

types (cts), riparian site types (rst), and plant associations (pas) are

listed below:

Area Classification Authority

AK general veg. pas Viereck & Dyress 1980

AK: interior postfire forest cts Foote 1983

nw AK forest veg. cts Hanson 1953

CO forest hts Arno & Presby 1977

CO hts Powell 1988

w CO riparian veg. cts Baker 1989a

nw CO general veg. pas Baker & Kennedy 1985

CO: Arapaho & forest hts Hess & Alexander 1986

Roosevelt NF

CO: Gunnison & forest hts Komarkova & others 1988

Uncompahgre NF

c ID riparian cts, hts Tuhy & Jensen 1982

n ID forest cts, hts Cooper & others 1991

e ID, w WY forest hts Steele & others 1983

e ID, w WY riparian cts Youngblood & others 1985

MT riparian dts. Hansen & others 1988

MT forest hts Pfister & others 1977

c,e MT riparian veg. rst., cts, hts Hansen & others 1989

nw MT riparian cts Boggs & others 1990

sw MT riparian veg. rst, cts, hts Hansen & others 1989

wc MT wetland cts Pierce & Johnson 1986

UT: Uinta Mt. forest hts Henderson & other 1977

n UT forest hts Mauk & Henderson 1984

UT, se ID riparian cts Padgett & others 1989

WY riparian veg. rst Olson & Gerhart 1982

WY: c YELL riparian hts Mattson 1984

PQ: Saint general veg. pas Darsereau 1957

Lawrence Valley

Yukon veg. types Stanek & others 1981

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

IMPORTANCE TO LIVESTOCK AND WILDLIFE:

Bluejoint furnishes a large amount of forage for many big game

species and livestock [16,18,38]. Occasionally it occupies considerable

areas to the exclusion of other native grasses [26]. Under such

conditions it yields a large amount of quality hay for livestock [26].

This grass is important forage for livestock in Alaska and is an

important component in the diet of bison herds in the Slave River

lowland, Northwest Territories, Canada [20]. It is grazed lightly by

deer but makes up a major part of the diet of elk in the winter [25,42].

PALATABILITY:

Bluejoint is most palatable when young and succulent. Since it

often grows in wet habitats, use by livestock is often limited until

late in the season when the grass is tough [18,38].

The relish and degree of use shown by wildlife species for bluejoint

in several western states has been rated as follows [8]:

MT ND UT WY

Pronghorn ---- Poor Poor ----

Elk Fair ---- Fair ----

Mule deer Poor Poor Fair ----

White-tailed deer Poor Poor ---- ----

Small mammals ---- ---- Fair Fair

Small nongame birds ---- ---- Fair Fair

Upland game birds ---- ---- Poor Poor

Waterfowl ---- Fair Poor Fair

NUTRITIONAL VALUE:

Bluejoint has been rated as fair in energy value and poor in

protein value [8,15]. In July of 1974, nutrient and mineral composition

of this grass on Alaska's Kenai Peninsula were as follows [29]:

IVDMD(%)* Fiber % Protein %

Moose Dairy Cow Cell walls ADF* Lignin

48.1 55.9 69.8 37.8 3.7 9.8

* IVDMD=in vitro dry-matter digestibility

* ADF=acid detergent fiber

macronutrients (ppm) micronutrients (ppm)

Ca K Mg Na Cu Fe Mn Zn

617.0 9799.0 1481.0 74.0 22.3 58.0 30.9 21.6

COVER VALUE:

The degree to which bluejoint provides environmental

protection during one or more seasons for wildlife species has been

rated as follows [8]:

MT ND UT WY

Pronghorn ---- ---- Poor Poor

Elk ---- ---- Poor ----

Mule deer ---- Fair Poor ----

White-tailed deer ---- Good ---- ----

Small mammals Poor ---- Fair Fair

Small nongame birds Poor ---- Fair Good

Upland game birds Poor ---- Fair Fair

Waterfowl Good Fair Fair Fair

VALUE FOR REHABILITATION OF DISTURBED SITES:

The rhizomatous nature of bluejoint helps provide streambank

stability. This is particularly important on higher gradient streams

where scouring by seasonal flooding is possible [4]. This grass is a

vigorous invader of oil spill sites in the Northwest Territories,

Canada, and recovers rapidly after spills [16]. Bluejoint was

evaluated for revegetation in tundra and northern boreal forest sites.

It established slowly, but by the end of the growing season, cover and

biomass production equaled or exceeded those of commercial varieties.

Seed of bluejoint has been collected for revegetation trials

in Alberta [16].

OTHER USES AND VALUES:

NO-ENTRY

OTHER MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

Grazing: Bluejoint is sensitive to overgrazing. Yields

decreased by 15 to 20 percent when bluejoint was cut two to

four times during the growing the season, by 35 to 45 percent when cut

five to six times, and about 70 percent when cut seven times, when

compared to plots cut once at the end of the growing season [16].

Grazing should be restricted when soils are moist, especially along

streams where bank sloughing can occur [13]. Livestock use should be

timed according to both the drying of soil surface and the maturation of

the seedheads. Livestock should be removed when 40 percent or less

utilization of herbaceous forage is obtained [13].

Insect and disease: Some bluejoint strains are susceptible to white

top. This condition is caused by insect or fungal damage of the lower

culms. Bluejoint, in general, is not susceptible to snow mold [16].

Site competitor: Bluejoint is a serious competitor of

regeneration of conifer seedlings on disturbed moist sites. Bluejoint

often produces a thick, "mulch" of litter which insulates the

soil surface, causing the soil temperature to decrease. Cold soils

could partially explain the poor growth of conifer seedlings that often

occurs after planting in bluejoint-dominated sites [19].

Control: Bluejoint can be controlled with glyphosate applied

after flowering and about the same time as aboveground senescence begins

[5].

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Bluejoint is a sod-forming, native, perennial, cool-season

grass [5,12,16,36]. Its blades are numerous and generally obtain a

height of 2 to 4 feet (60-120 cm) [12,16]. In Alaska, this grass has

been known to reach heights of up to 6.5 feet (200 cm) within 6 weeks

[16]. This grass is long-lived. Well-developed fields may persist for

as long as 100 years [16]. Creeping underground rhizomes are extensive

and fibrous roots are shallow [16,32,36,38].

RAUNKIAER LIFE FORM:

Hemicryptophyte

Geophyte

REGENERATION PROCESSES:

Sexual Reproduction: Bluejoint flowers are wind pollinated.

Prolific flowering, however, occurs only in wetlands and recently

disturbed sites [28]. The winged seeds are very lightweight and easily

wind-borne [16,28]. Seed yields are low, but seed can remain viable in

the soil for up to 5 years [6,16]. Seeds collected near Inuvik,

Northwest Territories, had a germination rate of 90 percent at 68

degrees Fahrenheit (20 deg C). Seedling vigor was rated as moderate

[3,16].

Vegetative Reproduction: Bluejoint can also reproduce

vegetatively by rhizomes [6,16,28,33,38]. This grass is capable of

producing an extensive network of rhizomes during a single growing

season. Small sections (two or more internodes) of several rhizomes can

produce shoots and establish new clones [28,33].

SITE CHARACTERISTICS:

Bluejoint occurs in a wide range of habitats from lowland wet

sites, semishaded woodlands, to windswept alpine ridges [16,18]. It

extends from sea level in the north and northwest to elevations of over

12,000 feet (3,658 m) near the southern limit of its range in New Mexico

[18,38]. It prefers moist sites but can survive in a wide range of

moisture regimes [16]. This grass, however, cannot germinate under

drought conditions, although it is very drought resistant once

established [16].

Soils: Bluejoint occupies sites with imperfectly to

moderately well-drained soils. It is found on both peat and mineral

soils, but most often on peat, and is adapted to a wide range of soil

textures. This grass is tolerant of extremely acidic soils, with pH

values as low as 3.5, and is moderately tolerant of saline soils

[8,16,19].

Plant associates: Bluejoint is commonly associated with the

following species: Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), fireweed

(Epilobium angustifolium), beaked sedge (Carex rostrata), tufted

hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa), Geyer willow (Salix geyeriana),

booth willow (Salix boothii), wolf's willow (Salix wolfii), subalpine

fir (Abies lasiocarpa), lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), and Engelmann

spruce (Picea engelmannii) [13,14,15,30,31,40,41].

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS:

Bluejoint is a common constituent in a number of seral and

climax communities. A combination of sexual and vegetative reproduction

allows this grass to persist throughout the successional continuum [4].

It is an aggressive ground residual colonizer and initial off-site

colonizer in early seral communities. Once established, a very dense

stand of bluejoint may persist almost indefinitely, severely

limiting the invasion of woody species [5]. In some mid-seral to climax

wetland forest communities and forest communities having high water

tables, bluejoint occurs as a dominant or codominant

understory species [13,14,15,31,40].

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT:

In general, bluejoint leaf and culm production occurs from

early May to mid-June followed by significant vegetative growth of shoot

biomass [5,19]. By mid-June flowering heads begin to emerge and by late

June to early July flowering begins [5,19]. Flowering peaks from late

June to mid-July. Aboveground senescence begins mid to late August

[5,19].

FIRE ECOLOGY

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

FIRE ECOLOGY OR ADAPTATIONS:

Bluejoint sprouts from on-site surviving rhizomes following

fire [7,28,35,37]. It can also establish on burned sites by

wind-dispersed seeds [7].

FIRE REGIMES:

Find fire regime information for the plant communities in which this

species may occur by entering the species name in the FEIS home page under

"Find Fire Regimes".

POSTFIRE REGENERATION STRATEGY:

Rhizomatous herb, rhizome in soil

Initial-offsite colonizer (off-site, initial community)

FIRE EFFECTS

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

IMMEDIATE FIRE EFFECT ON PLANT:

Fire will kill aboveground vegetation of bluejoint [35,37].

Severe fires will also kill belowground rhizomes [35,37].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF FIRE EFFECT:

Under droughty conditions dead shoots of bluejoint exhibit low

moisture content [20,37]. In small experimental fires in Inuvik,

Northwest Territories, dead litter sustained combustion, but the fire

merely burned around the live material [37].

PLANT RESPONSE TO FIRE:

Following low-severity fires, bluejoint will typically sprout

from on-site surviving rhizomes. Buried or wind-dispersed seeds may be

the primary source of plant establishment on severely burned sites

[28,37].

DISCUSSION AND QUALIFICATION OF PLANT RESPONSE:

Light surface burning tends to increase the abundance of bluejoint

[9,35,40]. Following a low-severity burn in a trembling aspen

(Populus tremuloides) woodland in southern Ontario, this species'

frequency was twice as high on burned areas. The abundance of bluejoint

4 months after the fires in 1973 was four times greater than

in the control areas and two times greater than in areas burned in 1972

[35].

Hamilton's Research Papers (Hamilton 2006a, Hamilton 2006b) and the following

Research Project Summaries provide information on prescribed fire and postfire

responses of many plant species, including bluejoint:

FIRE MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS:

When grazing pressure is light, litter accumulates rapidly [37].

Low-intensity fires can be used to remove this litter and improve forage

quality [22]. Because of wet conditions in the spring and summer,

successful burning of these communities is limited to the drier fall

period [4].

REFERENCES

SPECIES: Calamagrostis canadensis

REFERENCES:

1. Anderson, J. P. 1959. Flora of Alaska and adjacent parts of Canada.

Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. 543 p. [9928]

2. Bernard, Stephen R.; Brown, Kenneth F. 1977. Distribution of mammals,

reptiles, and amphibians by BLM physiographic regions and A.W. Kuchler's

associations for the eleven western states. Tech. Note 301. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 169 p.

[434]

3. Bliss, L. C.; Grulke, N. E. 1988. Revegetation in the High Arctic: its

role in reclamation of surface disturbance. In: Kershaw, Peter, ed.

Northern environmental disturbances. Occas. Publ. No. 24. Edmonton, AB:

University of Alberta, Boreal Institute for Northern Studies: 43-55.

[14419]

4. Boggs, Keith; Hansen, Paul; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John. 1990.

Classification and management of riparian and wetland sites in

northwestern Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of

Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station, Montana

Riparian Association. 217 p. Draft Version 1. [8447]

5. Conn, Jeffery S.; Deck, Richard E. 1991. Bluejoint reedgrass

(Calamagrostis canadensis) control with glyphosate and additives. Weed

Technology. 5: 521-524. [17408]

6. Conn, Jeffery S.; Farris, Martha L. 1987. Seed viability and dormancy of

17 weed species after 21 months in Alaska. Weed Science. 35: 524-529;

1987. [5]

7. Crane, M. F.; Fischer, William C. 1986. Fire ecology of the forest

habitat types of central Idaho. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-218. Ogden, UT: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research

Station. 85 p. [5297]

8. Dittberner, Phillip L.; Olson, Michael R. 1983. The plant information

network (PIN) data base: Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and

Wyoming. FWS/OBS-83/86. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior,

Fish and Wildlife Service. 786 p. [806]

9. Dyrness, C. T.; Norum, Rodney A. 1983. The effects of experimental fires

on black spruce forest floors in interior Alaska. Canadian Journal of

Forest Research. 13: 879-893. [7299]

10. Eyre, F. H., ed. 1980. Forest cover types of the United States and

Canada. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters. 148 p. [905]

11. Garrison, George A.; Bjugstad, Ardell J.; Duncan, Don A.; [and others].

1977. Vegetation and environmental features of forest and range

ecosystems. Agric. Handb. 475. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service. 68 p. [998]

12. Hallsten, Gregory P.; Skinner, Quentin D.; Beetle, Alan A. 1987. Grasses

of Wyoming. 3rd ed. Research Journal 202. Laramie, WY: University of

Wyoming, Agricultural Experiment Station. 432 p. [2906]

13. Hansen, Paul; Boggs, Keith; Pfister, Robert; Joy, John. 1990.

Classification and management of riparian and wetland sites in central

and eastern Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of

Forestry, Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station, Montana

Riparian Association. 279 p. [12477]

14. Hansen, Paul; Chadde, Steve; Pfister, Robert; [and others]. 1988.

Riparian site types, habitat types, and community types of southwestern

Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry,

Montana Riparian Association. 140 p. [5883]

15. Hansen, Paul; Pfister, Robert; Boggs, Keith; [and others]. 1989.

Classification and management of riparian sites in central and eastern

Montana. Missoula, MT: University of Montana, School of Forestry,

Montana Riparian Association. 368 p. Draft Version 1. [8934]

16. Hardy BBT Limited. 1989. Manual of plant species suitability for

reclamation in Alberta. 2d ed. Report No. RRTAC 89-4. Edmonton, AB:

Alberta Land Conservation and Reclamation Council. 436 p. [15460]

17. Harrington, H. D. 1964. Manual of the plants of Colorado. 2d ed.

Chicago: The Swallow Press Inc. 666 p. [6851]

18. Herzman, Carl W.; Everson, A. C.; Mickey, Myron H.; [and others]. 1959.

Handbook of Colorado native grasses. Bull. 450-A. Fort Collins, CO:

Colorado State University, Extension Service. 31 p. [10994]

19. Hogg, Edward H.; Lieffers, Victor J. 1991. The impact of Calamagrostis

canadensis on soil thermal regimes after logging in northern Alberta.

Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 21: 387-394. [14344]

20. Hogg, E. H.; Lieffers, Victor J. 1991. The relationship between seasonal

changes in rhizome carbohydrate reserves and recovery following

disturbance in Calamagrostis canadensis. Canadian Journal of Botany. 69:

641-646. [14343]

21. Hulten, Eric. 1968. Flora of Alaska and neighboring territories.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 1008 p. [13403]

22. Kantrud, Harold A.; Millar, John B.; van der Valk, A. G. 1989.

Vegetation of wetlands of the prairie pothole region. In: van der Valk,

Arnold, ed. Northern prairie wetlands. Ames, IA: Iowa State University

Press: 132-187. [15217]

23. Kartesz, John T.; Kartesz, Rosemarie. 1980. A synonymized checklist of

the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. Volume

II: The biota of North America. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North

Carolina Press; in confederation with Anne H. Lindsey and C. Richie

Bell, North Carolina Botanical Garden. 500 p. [6954]

24. Kuchler, A. W. 1964. Manual to accompany the map of potential vegetation

of the conterminous United States. Special Publication No. 36. New York:

American Geographical Society. 77 p. [1384]

25. Kufeld, Roland C. 1973. Foods eaten by the Rocky Mountain elk. Journal

of Range Management. 26(2): 106-113. [1385]

26. Lamson-Scribner, F. 1900. Economic grasses. Bulletin No. 14. Washington,

DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Agrostology. 85 p.

[4282]

27. Lyon, L. Jack; Stickney, Peter F. 1976. Early vegetal succession

following large northern Rocky Mountain wildfires. In: Proceedings, Tall

Timbers fire ecology conference and Intermountain Fire Research Council

fire and land management symposium; 1974 October 8-10; Missoula, MT. No.

14. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station: 355-373. [1496]

28. MacDonald, S. Ellen; Lieffers, Victor J. 1991. Population variation,

outcrossing, and colonization of disturbed areas by Calamagrostis

canadensis: evidence from allozyme analysis. American Journal of Botany.

78(8): 1123-1129. [15475]

29. Oldemeyer, J. L.; Franzmann, A. W.; Brundage, A. L.; [and others]. 1977.

Browse quality and the Kenai moose population. Journal of Wildlife

Management. 41(3): 533-542. [12805]

30. Padgett, Wayne G.; Youngblood, Andrew P.; Winward, Alma H. 1989.

Riparian community type classification of Utah and southeastern Idaho.

R4-Ecol-89-01. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest

Service, Intermountain Region. 191 p. [11360]

31. Pfister, Robert D.; Kovalchik, Bernard L.; Arno, Stephen F.; Presby,

Richard C. 1977. Forest habitat types of Montana. Gen. Tech. Rep.

INT-34. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 174 p. [1878]

32. Powell, David C. 1988. Aspen community types of the Pike and San Isabel

National Forests in south-central Colorado. R2-ECOL-88-01. Denver, CO:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region.

254 p. [15285]

33. Powelson, R. A.; Lieffers, V. J. 1991. Growth of dormant buds on severed

rhizomes of Calamagrostis canadensis. Canadian Journal of Plant Science.

71: 1093-1099. [17592]

34. Raunkiaer, C. 1934. The life forms of plants and statistical plant

geography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 632 p. [2843]

35. Smith, D. W.; James, T. D. W. 1978. Changes in the shrub and herb layers

of vegetation after prescribed burning in Populus tremuloides woodland

in southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Botany. 56: 1792-1797. [16400]

36. Stubbendieck, J.; Nichols, James T.; Roberts, Kelly K. 1985. Nebraska

range and pasture grasses (including grass-like plants). E.C. 85-170.

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, Department of Agriculture,

Cooperative Extension Service. 75 p. [2269]

37. Sylvester, T. W.; Wein, Ross W. 1981. Fuel characteristics of arctic

plant species and simulated plant community flammability by Rothermel's

model. Canadian Journal of Botany. 59: 898-907. [17685]

38. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1937. Range plant

handbook. Washington, DC. 532 p. [2387]

39. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2018.

PLANTS Database, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources

Conservation Service (Producer). Available: https://plants.usda.gov/.

[34262]

40. Viereck, L. A.; Dyrness, C. T.; Batten, A. R.; Wenzlick, K. J. 1992. The

Alaska vegetation classification. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-286. Portland,

OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest

Research Station. 278 p. [2431]

41. Youngblood, Andrew P.; Padgett, Wayne G.; Winward, Alma H. 1985.

Riparian community type classification of eastern Idaho - western

Wyoming. R4-Ecol-85-01. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Region. 78 p. [2686]

42. Gullion, Gordon W. 1964. Wildlife uses of Nevada plants. Contributions

toward a flora of Nevada No. 49. Beltsville, MD: U. S. Department of

Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, National Arboretum Crops

Research Division. 170 p. [6729]

43. Stickney, Peter F. 1989. Seral origin of species originating in northern

Rocky Mountain forests. Unpublished draft on file at: U.S. Department of

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire

Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT; RWU 4403 files. 7 p. [20090]

FEIS Home Page