Preparers

Sarah Hines, Northeastern Area & Northern Research Station and Amy Daniels, Washington Office Research & Development

Issues

Private forestland in the United States plays a very important role in mitigating climate change, but is subject to many stressors including the effects of climate change.

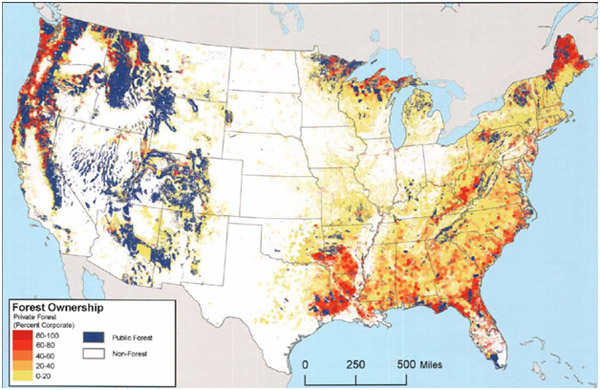

Globally, about 90 percent of forest lands are publicly owned, representing a range of de facto resource tenure arrangements (1). In contrast, ownership patterns are markedly different in the United States. Over half (56 percent) of America’s 750 million acres of forests are privately owned yet provide a vast array of public goods and services, such as wildlife habitat, clean water, timber and other forest products, and recreational opportunities, many of which are likely to be impacted by climate change (2). In the Northeast and Midwest states, the most densely populated region of the U.S., approximately 74 percent of the region’s forestland (128 million acres) is privately owned; in the Southeast, approximately 87% is privately owned (3; 4). The area and permanence of these private forests and the benefits that they provide are not guaranteed. Yet these private forest lands are critical to mitigating climate change and, because of their often smaller and more fragmented nature, may be even more vulnerable to its effects.

Climate change impacts, coupled with fragmented forestland ownership trends and continued population expansion, poses a threat to the existence and health of private forestland in the U.S. As with any forest, privately owned forests sequester carbon as they grow, acting as a carbon storage "bank" and helping to partially offset global fossil fuel emissions; while the forest temporarily releases part of this carbon to the atmosphere if trees are cut or burned, the forest permanently releases practically all of its carbon if it is converted to non-forest uses. The integrity of the globally-significant national carbon bank depends on the continued existence and sustainable management of much of America’s private forestland. When forests are permanently converted to non-forest use, not only does the capacity of the terrestrial carbon bank decrease, but the converted land-use can create secondary conditions that exacerbate climate change (e.g., a forest converted to a suburb means more construction, transportation, and residential emissions; a forest converted to a conventional farm means fertilizer, tractor, and transportation related emissions). Moreover, conversion of private forests to other land uses compromises the pivotal role that forests play in regulating water balance, facilitating aquifer recharge, and providing habitat connectivity--all increasingly important for society’s adaptation to climate change (5).

Expected Changes

The 420 million acres of private forestland in the U.S. is held by approximately 11 million owners. Of these, approximately 8 million owners have land holdings smaller than 50 acres (3). Larger private forest landowners, including organizations, corporations, and individuals, may have landholdings of 5,000 acres or more but are far fewer in number. Tax laws, demographics, and other economic factors can affect ownership and parcelization patterns and trends. Over 60 percent of private forest landowners in the U.S. are age 55 or older; combined, these landowners own 170 million acres of forest or over 40 percent of private forestland. As a result of these demographics, a substantial portion of private forestland is expected to change ownership in the coming decades; some of these tracts may stay intact, while others will be fragmented and developed (7; 3).

Landowners have many reasons for wanting to own forestland, but can be generally grouped into four general categories: woodland retreat owners, supplemental income owners, working the land owners, and uninvolved owners. Each of these landowner groups is motivated by a different set of values and beliefs. More research on each of these landowner segments and their associated values and beliefs can be found on the Tools for Engaging Landowners Effectively (TELE) website. Not all landowners are interested in or aware of the possibilities for ensuring the long-term preservation of their land as forest (e.g. creating legacy plans for passing on their land to heirs, placing a conservation easement on the land, etc.). Some landowners may value their forestland more as a present-day asset (used to generate timber or other marketable ecosystem services), as an investment that can be sold and developed for a profit at a later date, or simply as a quiet retreat.

Recent analysis suggests that up to 57 million acres of privately held rural forestland could experience a substantial increase in housing density from 2000 to 2030 (2). Many forested watersheds on the east coast as well as those immediately adjacent to large metropolitan areas are most at risk of being developed. As forested watersheds are developed, water quality is expected to decline. In addition, management options for forest land located next to developed areas dwindle as the shrinking forest is less able to support the timber product industry infrastructure that makes management possible and profitable. Management can be much more expensive on small or fragmented forested parcels, because it is costly to move machinery and timber revenue may be slight. This means management options intended to improve forest health or resilience, such as sustainable thinning or harvesting, are increasingly unavailable or prohibitively expensive for private landowners on smaller or fragmented parcels, or parcels surrounded by development. Large tracts of unfragmented forest and intact watersheds can be more effective at sequestering carbon and more resilient to climate change impacts than fragmented forests and watersheds. Large tracts, whether owned individually or collectively, also comprise ecosystems that are bigger and more complex than the sum of their parts; these lands can often support more robust wildlife populations (8) and enable economically viable timber harvesting and management, asecologically appropriate. While active management is not suitable for all lands, sustainable management can enhance forest health (9). Improving wildlife habitats, eliminating invasive species, helping to control the spread of disease, and restoring key ecosystem conditions and processes after disturbance increases resilience to climate change (10). Some of these management practices may also support rural economic livelihoods through the forest products industry.

Options for Management

Private lands provide a wealth of public benefits. Because landowners are typically not financially compensated for the benefits that their land provides, critical ecosystem services are usually not maintained at optimal levels (11). Conversely, the social cost of permanently losing forest to other land uses applies to society at large (e.g., diminished aquifer recharge), even though the associated revenues for land use conversion typically accrue to the landowner alone. In this context, a range of policy tools, from local initiatives to national programs, engage private forest landowners to consider options and opportunities for forest stewardship. Some policies are restrictive, such as Maryland land use ordinances that aim to achieve zero net forest loss.*More common are policy tools that use incentives to influence the land use choices of private landowners. From technical extension services, to tax incentives and easements, to direct financial incentives, a forest landowner may craft a custom arrangement for their location and needs that supports continued or enhanced forest stewardship. For example, after developing and adopting a forest stewardship plan, a woodland owner may access technical assistance through the USDA Forest Service Forest Stewardship Program, and may apply for a host of other land stewardship resources offered through other federal incentive programs, many of which are managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (Table 1).

* S.B. 666, October 1, 2009

Program (Agency) | Acronym | Description | Area Enrolled (millions of acres) | Carbonin eligibility criteria? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation Reserve (FSA) | CRP, CCRP CREP | Financial incentives to retire marginal cropland and establish grass or tree cover for 10 or 15 years, respectively. | ~31 | Yes |

| Forest Legacy (USFS) | FLP | Market value compensation of development rights for protecting sensitive forest lands at risk of conversion via permanent easements. | ~1.98 | No |

| Forest Stewardship (USFS) | FSP | Technical and educational assistance to promote sustainable forest stewardship. | ~34 (>300,000 plans) | Yes |

| Urban & Community Forestry (USFS) | UCF | Promotes community and urban forestry initiatives, including competitive grants | n/a | Yes |

| Farm & Ranch Lands Protection (NRCS) | FRPP | Up to 50% of market value compensation for permanent easement to preserve agricultural use of farms/ranches. | >0.53 (1996-2007) | Yes |

| Healthy Forest Reserve (NRCS) | HRFP | Cost-share for restoration plus compensation for up to 100% of development rights for permanent easements, to benefit threatened & endangered species, biodiversity & carbon sequestration. | n/a | Yes |

| Wildlife Habitat Incentives (NRCS) | WHIP | Financial incentives to restore habitat for wildlife benefits | 0.65 | No |

| Environmental Quality Incentives Program (NRCS) | EQIP | Technical & financial assistance for implementing practices (such as installing structural, vegetative, and land management practices) that alleviate conservation problems and create environmental | 16.8 | No |

Easements, such as those through the Forest Legacy Program, provide tax benefits and typically allow woodland owners to sustainably harvest according to the terms of the easement. Other programs include cost-share assistance for management practices or restoration activities toward achieving a particular conservation goal such as wildlife habitat restoration. Many of these programs consider carbon storage or sequestration in their eligibility criteria. This means that in addition to ensuring benefits like clean water and habitat that are increasingly vital in the context of a changing climate, these programs help continue private forests' role as carbon sinks. In addition to classic market-based uses of forest land, such as for hunting leases, the carbon market provides another option in some places to generate land rent from forestry. In the US, forest activities that meet accepted project protocols for afforestation/reforestation, improved forest management, and/or avoided conversion have the potential to generate carbon credits that may be sold on the Over-the-Counter (OTC) market (or potentially on California's regulated market, beginning in 2012) to offset carbon emissions by other industries. Substantial start-up costs and fixed transaction costs associated with generating carbon credits often make this prohibitively expensive for small private forest landowners. Carbon market engagement may only be an economically viable opportunity for larger landowners or through small project aggregation (12).

Maintaining vital private forest lands in the U.S. hinges on both eliminating penalties and creating incentives for responsible, long-term forest stewardship. Through incentives ranging from tax benefits, to cost-share assistance and payments, to the sale of carbon credits, landowners interested in maintaining forest on their land have several options to reduce or reverse the opportunity cost sometimes associated with responsible forest stewardship; however, some of these mechanisms may only be feasible to larger landowners. When considered collectively across landscapes and regions, the effects on maintaining forest cover and forest connectivity-essential to both mitigating and adapting to climate change-are significant (13).

Targeting conservation incentives to forest resources with the highest ecological and social values that also are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts or conversion to non-forest uses would require identifying those resources (for example, though a Vulnerability Assessment) and setting policy priorities.

Hines, S.J.; Daniels, A. 2011. Private Forestland Stewardship. (October 10, 2011). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Climate Change Resource Center. www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/forest-stewardship

LaRocco, G.L.; Deal, R.L. 2011. Giving credit where credit is due: increasing landowner compensation for ecosystem services. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-842. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 32 p.

Peters-Stanley, M.; Hamilton, K.; Marcello, T.; Sjardin, M. 2011. State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2011. Ecosystem Marketplace and Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

Carbon markets are evolving quickly, and even recently-published documents can be slightly outdated. The following two documents are great introductions to carbon market basics, although please be aware that the policy and market context has changed since their publication. In particular, the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) discussed in both documents closed operations in 2010.

Brooke, R. 2009. Payments for Forest Carbon: Opportunities and Challenges for Small Forest Landowners. Northern Forest Center, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, and Coastal Enterprises Inc.

Diaz, D. D.; Charnley, S.; Gosnell, H. 2009. Engaging western landowners in climate change mitigation: a guide to carbon-oriented forest and range management and carbon market opportunities. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-801. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 81 p.

PINEMAP: Mapping the future of southern pine management in a changing world

The PINEMAP project integrates research, extension, and education to enable southern pine landowners to manage forests to increase carbon sequestration; increase efficiency of nitrogen and other fertilizer inputs; and adapt forest managment approaches to increase forest resilience and sustainability under variable climates.

Contact: Asko Noormets

Forest Economics and Policy

Shifting climate patterns contribute to changing disturbance regimes in southern forests (insect outbreaks, fire) and, in turn, affect the economic costs of these disturbances. Climate change may also play a role in the societal values placed on forest resources. This research unit explores many of the complex relationships that exist between changing forests conditions, human communities, and economic processes.

Contact: David Wear

Social and Economic Analysis of the Effects of Climate Change

Presented in a series of briefing papers, the main topics addressed here are effects of climate change on wildlife habitat, other ecosystem services, and land values; socioeconomic impacts of climate change on rural communities; and competitiveness of carbon offset projects on nonindustrial private forests in the United States.

Contacts: Ralph Alig, Evan Mercer

- Global Forest Resources Assessment, 2005. Food and Agriculture Organization. (23 March, 2009).

- Stein, Susan M.; McRoberts, Ronald E.; Mahal, Lisa G.; Carr, Mary A.; Alig, Ralph J.; Comas, Sara J.; Theobald, David M.; Cundiff, Amanda. 2009. Private forests, public benefits: increased housing density and other pressures on private forest contributions. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-795. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 74 p.

- Butler, B. J. 2008 (b). Family Forest Owners of the United States, 2006.Gen. Tech. Rep.NRS-27. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 73 p.

- Smith, W.B.; Miles, P.D.; Perry, C.H.; Pugh, S.A. 2009. Forest resources of the United States, 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 336 p.

- Thompson, I.; Mackey, B.; McNulty, S.; Mosseler, A. (2009). Forest Resilience, Biodiversity, and Climate Change. A synthesis of the biodiversity/resilience/stability relationship in forest ecosystems. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal. Technical Series no. 43, 67 pages.

- Nelson, M.D.; Liknes, G.C.; Butler, B.J. 2010. Map of forest ownership in the conterminous United States. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station.

- Butler, B. J. 2008 (a). Forest ownership patterns are changing. National Woodlands. spring: 8-9.

- MacArthur, R. H.; Wilson, E. O. 1967. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- The Montreal Process. Criteria and Indicators for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate Boreal Forests. [pdf] Fourth Edition, October 2009.

- Millar, C.; Stephenson, N.L.; Stephens, S.L. 2007. Climate Change and Forests of the Future: Managing in the Face of Uncertainty. Ecological Applications 17(8): 2145-2151.

- Mercer, D.E.; Cooley, D.; Hamilton, K, 2011. Taking Stock: Payments for Ecosystem Services in the United States. Forest Trends & Ecosystem Marketplace.

- Brooke, R, 2009. Payments for Forest Carbon: Opportunities and Challenges for Small Forest Owners. [pdf] Northern Forest Center, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, Coastal Enterprises, Inc.

- Donald, P. F. and Evans, A. 2006. Habitat connectivity and matrix restoration: the wider implications of agri-environment schemes. Journal of Applied Ecology 43(2): 209-218.

- Stein, Susan M.; McRoberts, Ronald E.; Mahal, Lisa G.; Carr, Mary A.; Alig, Ralph J.; Comas, Sara J.; Theobald, David M.; Cundiff, Amanda. 2009. Private forests, public benefits: increased housing density and other pressures on private forest contributions. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-795. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 74 p.

- Butler, B. J. 2008 (b). Family Forest Owners of the United States, 2006. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-27. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 73 p.

- Smith, W.B.; Miles, P.D.; Perry, C.H.; Pugh, S.A. 2009. Forest resources of the United States, 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 336 p.

- Thompson, I.; Mackey, B.; McNulty, S.; Mosseler, A. (2009). Forest Resilience, Biodiversity, and Climate Change. A synthesis of the biodiversity/resilience/stability relationship in forest ecosystems. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal. Technical Series no. 43, 67 pages. http://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-43-en.pdf

- Millar, C.; Stephenson, N.L.; Stephens, S.L. 2007. Climate Change and Forests of the Future: Managing in the Face of Uncertainty. Ecological Applications 17(8): 2145-2151.

- Donald, P. F. and Evans, A. 2006. Habitat connectivity and matrix restoration: the wider implications of agri-environment schemes. Journal of Applied Ecology 43(2): 209-218.