Chapter 7—Planning Recreation Sites

The prerequisite for developing any recreation site is access and permission to use the area. Other factors that come into play include: user preferences, safety, budgets, legal requirements, site limitations, and climate. A good recreation site meets the needs of users, minimizes conflicts, and has an appropriate level of development, while protecting the natural environment. Careful planning is the key to a successful equestrian recreation site, whether it is a trailhead, single-party campground, group camp, or a combination of the three.

User Needs

The needs of equestrians are similar to the needs of other users. For example, all recreationists need water. Riders not only need a need a water source, they need one that accommodates their stock.

Because riders' preferences vary greatly across the country, when planning recreation sites for equestrians, arrange a public meeting to gather input. Invite representatives from a wide range of equestrian organizations. If equestrian trailheads and campgrounds are nearby, visit them. While there, ask riders what they like about the facilities and what they would like to improve.

Site Conflicts

If recreation user groups are not fully compatible, safety may become an issue. For example, many children are not horsewise. They may play in ways that startle horses and mules. Adults who are not familiar with stock might unintentionally create problems as well. People, stock, and facilities could be harmed in such situations. Riders appreciate separation from other users in campgrounds, at trailheads, and at trail access points. Landforms, roads, streams, drainages, and vegetation can be used for separation. Suggested separation strategies include:

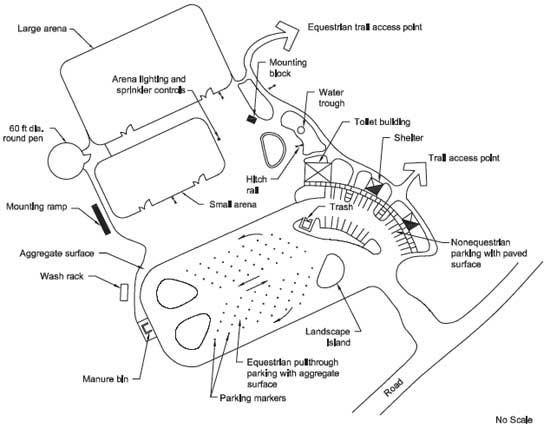

- Trailheads and campgrounds—Design sites to

avoid disturbances between trailhead visitors

and equestrian campers. Figure 7–1 shows a site

where distance separates vehicles traveling to the

campground from trailhead users.

- Equestrian and nonequestrian campgrounds— Restrict equestrian campgrounds to campers who

have stock. Provide substantial separation between

equestrian and nonequestrian campgrounds. Keep

nonequestrian users away to reduce the potential

for inadvertent injury. Figure 7–2 shows a site

where equestrian and nonequestrian campgrounds

are separated by distance and a highway.

- Single-party equestrian camping and group

equestrian camping—Separate the single-party

equestrian sites from those designed for groups.

Single-party campers appreciate a buffer, because

large groups may be loud.

- Equestrian and nonequestrian trailhead parking— Separate equestrians and other users at trailhead parking areas. Post signs indicating where groups should park. The separation does not need to be extensive, because visitors don't stay in parking areas very long, making conflicts less likely. Figure 7–3 shows a trailhead with facilities and vegetation that separate conflicting user groups. Some agencies also provide separate trail access points for conflicting user groups. Signs should identify access points for different types of users and educate users about appropriate behavior around stock.

Figure 7–1—A recreation site where distance separates vehicles

traveling to the equestrian campground from the trailhead.

Figure 7–2—A recreation site where distance and a highway separate the equestrian

and nonequestrian campgrounds. For long description click here.

Figure 7–3—A trailhead where facilities and vegetation separate

conflicting user groups.

Trail Talk

The Army Way

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2004) follows these guiding principles when designing recreation sites:

- Consider functional use, creative design,

environmental harmony, and economy of

construction.

- Maintain health, safety, security, and comfort

of the users in all aspects.

- Meet local and regional recreation needs.

- Consider the present requirements as well as

recreation trends and future needs.

- Create user-friendly areas and facilities

to serve all populations.

Universal design

principles help ensure accessibility and user

diversity.

- Consider economy of scale and life-cycle costs.

- Enhance revenue generation.

- Base the design of facilities on an area's

anticipated average weekend day visitation

during the peak season of operation.

- Protect resources from physical and esthetic

degradation.

- Incorporate off-the-shelf products wherever

practical.

- Correct existing design problems.

- Provide for ease and economy in cleanup and

maintenance.

- Meet stated management and sustainable development goals.

Appropriate Levels of Development

Will a trailhead or campground have minimal equestrian facilities and offer an opportunity to get away from it all, or will there be extensive modern conveniences? The answer to this question describes the site's level of development. A recreation site's level of development accommodates the land management agency's master plan and the setting. This guidebook uses the terms low, moderate, and high development as subjective classifications describing the degree of manmade change in developed recreation sites. The levels of development for recreation sites roughly correspond with the roaded natural, rural, and urban recreation classifications of the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) Users Guide (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 1982). The Wilderness Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (WROS) is beyond the scope of this guidebook. Normal development for ROS classes is defined as:

- Roaded natural areas—Rustic facilities provide

some comfort for users as well as site protection.

Contemporary rustic design is usually based on

native materials, and synthetic materials are not

evident. Site modification is moderate.

- Rural areas—Some facilities are designed primarily

for user comfort and convenience. Synthetic but

harmonious materials may be incorporated. The

design may be more complex and refined. Site

modification for facilities is moderate to heavy.

- Urban areas—Facilities are designed mostly for user comfort and convenience. Synthetic materials are commonly used. Facility design may be highly complex and refined, but is in harmony with or complements the site. Site modification for facilities is extensive.

Site Selection

The ultimate site for equestrian trailheads and campgrounds has the following:

- Convenient driving access—The site has access roads that accommodate vehicles towing horse

trailers. Many trail users prefer a site that is within

5 miles (8 kilometers) of a paved road.

- Trail access—The site accesses a trail system. Riders

staying in a campground for several nights generally

prefer to travel a different loop trail each day.

- Mild terrain—The site has somewhat level

ground. As long as portions of the site are suitable

for building, some existing natural drainages

and landforms may serve as buffers between

conflicting uses.

- Good soil conditions—The site has soils that

percolate water quickly to avoid wet or muddy

conditions. Such soils also withstand traffic

without excessive compaction or erosion.

- Areas of existing vegetation—The site's tree

canopy provides at least partial shade. An

understory serves as a natural visual buffer.

Vegetation serves to separate conflicting uses.

- Areas of minimal vegetation—The site has a

natural opening surrounded by trees and shrubs

that is suitable for parking areas, eliminating the

need to remove existing vegetation.

- Adequate size—The site has sufficient area for

the project. If the site is not large enough for the

planned facilities, resource damage is likely.

- Suitable landscape—The site allows facilities to blend with the natural topography. Avoid a site that would make the recreation facilities prominent features when viewed from surrounding roads, trails, recreation sites, residences, or commercial properties.

Horse Sense

Gentle Slopes

Choosing trailhead and campground sites with steep terrain has its pitfalls. Steep terrain has design limitations and results in unsightly cuts and fills. The most desirable natural slope is about 1 to 3 percent, and the maximum is 4 percent. These gentle slopes allow construction of roads, parking areas, structures, camp units, and picnic units without extensive earthwork.

A thorough site analysis is invaluable. When archeological or cultural resources are present, or if plants or wild animals are classified as threatened or endangered, the complexity of planning and design can increase significantly. Deciding to build on flood plains may increase construction and maintenance costs.

Resource Roundup

Designing Choices: ROS

The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) Users Guide is an inventory and management tool used extensively on lands managed by the Forest Service. The ROS provides a framework for understanding environmental settings as they relate to recreation experiences, recognizing that the user's goal is to have satisfying experiences. Users achieve satisfaction by participating in their preferred activities in preferred environmental settings. For example, camping in an undeveloped setting offers some users a sense of solitude, challenge, and self-reliance. In contrast, camping in a setting with easy access and highly developed facilities offers some users more security, comfort, and social opportunities.

The ROS framework is set up on a continuum—the spectrum—that helps managers provide broad recreation choices. The continuum encompasses six classes that range from primitive to urban (figure 7–4). The combination of activities, settings, and experience opportunities in each class determines management and development strategies. For example, a facility intended to create a safe, controlled environment for large numbers of people would be highly developed using modern materials and would offer ample conveniences. A more primitive area would have far fewer constructed features than an urban area, and the features would be smaller and made of natural materials. The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum Users Guide is available at http://www.fs.fed.us/r4/ashley/projects/forest_plan_revision/ros.shtml.

Figure 7–4—The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum provides inventory and management tools for recreation settings. The levels

of trail development used in this guidebook roughly correspond with nonmotorized portions of the roaded natural, rural, and urban

recreation classifications.

Resource Roundup

Protecting Views: SMS and VRM

The Forest Service uses the Scenery Management System (SMS) to protect landscape views. The SMS presumes that land management activities—including construction of recreation sites—should not contrast with the existing natural appearance of the landscape. Regional character types are used as a basis for design. Form, line, color, and texture that blend with the landscape can be incorporated into the regional character type to minimize the visual impact of structures. This approach reinforces the concept that recreation sites should be visually subordinate to the landscape. The SMS is included in The Built Environment Image Guide (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service 2001). The guide is available at http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/beig.

The Bureau of Land Management uses a similar concept, the Visual Resource Management (VRM) system, to maintain scenic values on public lands. The VRM system is a method of identifying and evaluating scenic values to determine appropriate levels of management. Managers can analyze potential visual impacts and apply visual design techniques so development is in harmony with the surroundings. More information is available at http://www.blm.gov/nstc/VRM.

Vegetation and Landscaping

A vegetation management plan usually is part of the recreation site master plan. Silviculturists, botanists, or other specialists evaluate existing conditions and species for health, hardiness, age, longevity, and similar factors that influence proposed landscape changes. Subsequent recommendations will vary by climate and region of the country. For example, in heavily forested sites it may be desirable to remove some vegetation, providing clear areas open to the sun. In hot climates, priorities may include saving existing vegetation and preserving shade.

Toxic Vegetation

When planing equestrian amenities and facilities, avoid any vegetation that is toxic to horses and mules. If there's just a little toxic vegetation, remove it. Otherwise, consider moving the amenity away from the toxic vegetation. If it is impractical to avoid a large patch of toxic vegetation, post notices at information stations to alert riders about the hazards.

Noxious Weeds

Noxious weeds affect the health of the recreation site. Seeds often arrive inadvertently in hay and straw, on vehicles and clothing, and in hair and manure. The seeds germinate and proliferate quickly. Address the issue with handouts, notices, and signs, as appropriate. Consult Chapter 13—Reducing Environmental and Health Concerns for more information regarding toxic and noxious vegetation.

Resource Roundup

Tasty but Toxic

There are hundreds of toxic plants in North America, and many of them are common. Ten Most Poisonous Plants for Horses (EQUUS June 2004) ranks the ones of most concern to equestrians:

- Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

- Hemlock (Conium maculatum)

- Tansy ragwort (Senecio spp.)

- Johnsongrass and Sudan grass (Sorghum spp.)

- Locoweed (Astragalus spp. or Oxytropis spp.)

- Oleander (Nerium oleander)

- Red maple (Acer rubrum)

- Water hemlock (Cicuta spp.)

- Yellow star thistle and Russian knapweed (Centaurea spp.)

- Yew (Taxus spp.)

The article is available at http://www.equisearch.com/horses_care/feeding/feed/poisonousplants_ 041105.

Toxic Plants Web Guides

Several Web sites provide additional information about plants that are toxic to horses and mules:

- Cornell University provides the Poisonous

Plant Informational Database (2006) with

pictures of plants and affected animals, and

information about the botany, chemistry,

toxicology, diagnosis, and prevention of animal

poisoning by natural flora. The information is

available at http://www.ansci.cornell.edu/plants.

- Table 04: Poisonous Range Plants of Temperate North America, in the online Merck Veterinary Manual (Merck & Co., Inc. 2008) lists the vegetation dangerous to animals. The table gives the vegetation’s dangerous season, the scientific name, common name, habitat and distribution, important characteristics, toxic effects, and comments and treatment. The table is available at http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/htm/bc/ttox04.htm.

Toxic Plants Field Guide

Another popular reference is Horse Owner's Field Guide to Toxic Plants (Burger 1996). The guide describes well-known plants in the United States that are poisonous or otherwise dangerous to stock.

Amenities and Facilities

Equestrian facilities and amenities—trail access, water sources, toilets, corrals, and so forth—help determine the value of a site (figure 7–5). The most important elements at trailheads and campgrounds are trail access, convenient toilet buildings, and a sturdy place to secure stock. Potable water is highly desirable, although in some areas recreationists bring their own water. Table 7–1 summarizes the relative desirability of selected facilities and amenities at recreation sites. Figures 7–6, 7–7, and 7–8 show suggested placement of facilities and amenities at a trailhead, a single-party campground, and a group camp. Consult Chapter 10—Securing Horses and Mules, for more information about confinement options.

Figure 7–5—This open camp unit has parking, an area for setting

up a tent, a fire surface, and a picnic table. Other campground

facilities include a manure bin, toilet buildings, and common

water hydrants. In the region where it is located, this campground

is considered high development. In other areas, this campground

would be considered low to moderate development.

—Courtesy of

Kandee Haertel

Figure 7–6—Suggested locations for facilities at an equestrian trailhead with a

high level of development. For long description click here.

Figure 7–7—Suggested locations for facilities at a single-party equestrian

camp

unit with a moderate level of development.

Figure 7–8—Suggested locations for facilities at an equestrian group camp with

a moderate level of development.

Trail Access Points

The primary feature of a successful equestrian trailhead and campground is a well-planned trail system. Once riders have established their camp, they don't like to transport stock to another location. Provide access to numerous loop trails directly from horse camps and trailheads. Consult Chapter 4—Designing Trail Elements for more information regarding loop trails.

Trail access points should be in places that are convenient, easy to find, and avoid user conflicts. If a recreation site has both a trailhead and a campground, provide separate trail access points leading from each facility and merge them some distance away. Because stock tend to defecate in the first half mile (0.8 kilometer) of a ride, separating trail access points for riders and other recreationists also reduces the manure on trails used by others.

Locate campground trail access in a public area that minimizes disturbance to visitors in single-party camp units. Trail access is best located at the end of a loop road or road intersection. These locations encourage riders to use the road instead of riding through someone else's camp unit. In group camps or trailhead parking areas, locate trail access points at the end of parking areas (see figures 7–6, 7–7, and 7–8).

Utilities

Recreation site utilities may include storm drainage, water, waste disposal, and power systems. The main factors that determine which utilities to provide at a recreation site are the site's proximity to existing utilities, the budget, and the level of development.

Sewer-, water-, and power-system design varies by geographic region. For example, water conservation is important in arid regions. Urban areas have access to existing water systems that may be sophisticated, while some northern regions use wells that require frost-free hydrants. Electrical systems may access a power grid or use solar power. No matter what system is chosen, utility design must be completed by qualified engineers and adhere to applicable local, State, and Federal building and regulatory codes.

Installing utility lines in a recreation site can affect vegetation and esthetics, often leaving a bare corridor the width of a road. Sensitive design minimizes these impacts by placing utility lines parallel and adjacent to the edges of new roads, along abandoned roads, or on a route that is already devoid of vegetation. If this is impractical, use the newly cleared area for pedestrian routes or structures. Where feasible, bury powerlines.

Resource Roundup

According to Code

The International Code Council (ICC) Web site lists the most widely adopted series of building codes in the United States. The ICC develops the codes used to construct residential and public buildings and is dedicated to fire prevention and structure safety. More information is available at http://www.iccsafe.org/cs.

Storm Drainage Systems

Storm drainage systems should carry off surface water without affecting site esthetics. Grades must direct surface waterflow away from living areas, toilet buildings, and hardened surfaces. Recreation site roads, parking areas, and pathways also must be sloped slightly to drain. Wherever possible, concentrate and collect surface flows in areas that are not visible. It may be possible to minimize impact on the land by using several small inlet structures close to one another instead of one large inlet. Regardless of the complexity of the system, proper design must follow State law and will require an interdisciplinary team that includes an engineer, hydrologist, and landscape architect.

Water Sources

Provide convenient stock water access—an average 1,500-pound (6,680-kilogram) animal needs about 15 gallons of water daily—more if the animal is active. Fifteen gallons of water weighs about 125 pounds (56.7 kilograms), quite a load to haul in buckets. Suitable water sources include water hydrants and water troughs.

Water Hydrants and Troughs

When stock share water sources, there is a potential for disease transmission. Because of this, many riders bring their own water and don't permit their horses and mules to use a shared source. Some riders prefer filling their own bucket at a hydrant, and then they take the bucket to the animal (figure 7–9) or bring the animal to the bucket. Other riders prefer the convenience of having a water trough. To meet the needs of all riders, provide both water hydrants and troughs. At a minimum, provide a water trough and hydrant at each toilet building and at trail access points. Riders also appreciate hydrants at group gathering areas. For user convenience, consider installing hydrants as suggested in table 7–2.

Figure 7–9—An average horse requires about 1 gallon of water

daily for each 100 pounds of body weight. Trail stock generally

weigh between 750 and 1,500 pounds. Draft horses, such as these

Percherons, can weigh 2,000 pounds or more.

—Courtesy of the

Forest Preserve of DuPage County, IL.

| Facility | Maximum distance from camp unit, picnic unit, or horse trailer (feet) |

|---|---|

| Water hydrant | 150 |

| Water trough | 300 |

Locate hydrants and troughs along the outside edges of loop roads, at intersections, or along the perimeter of parking areas. These locations encourage users to travel the road instead of cutting through camp units (see figures 7–6, 7–7, and 7–8). In highly developed areas where one hydrant serves two campsites, designers may want to incorporate split faucets and controls. Split faucets are not commonly available, but can be custom fabricated. Local health and safety codes may require backflow prevention systems or other considerations for custom configurations.

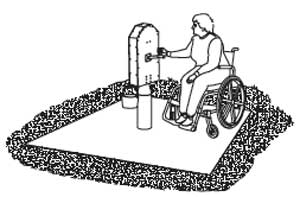

Accessible Hydrants and Handpumps

In areas with existing water lines, water access for riders with disabilities usually is not a problem. Many hydrant models are commercially available to meet needs at these sites. The Americans with Disabilities/Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADA/ABAAG) require that the controls can be operated with one hand without tight grasping, pinching, or wrist twisting. The force required to operate the control can't be more than 5 pounds (2.3 kilograms), and control heights must be between 15 and 48 inches (about 381 to 1,220 millimeters) above the ground. To be accessible, the handpump (figure 7–10) must be on a firm and stable surface that is clear of any obstructions for at least 60 by 60 inches (1,524 by 1,524 millimeters). This design allows someone in a wheelchair to approach the hydrant from the front or side, turn around, and leave. If the hydrant is an unusual design with the handle and spout on different sides of the post, be sure that people can access both sides.

Because available options for stand-alone handpumps that meet accessibility requirements are limited, MTDC designed the accessible handpump shown in figure 7–11. The pump complies with the grasping, turning, and operating force restrictions for people with disabilities. The design works with wells that are about 50 feet (15.2 meters) deep. No commonly available handpumps meet accessibility requirements for wells deeper than 50 feet.

Figure 7–10—This accessible hydrant has easy-to-use controls, a

drain, and a firm and stable surface for wheelchairs.

Resource Roundup

Accessible Handpump

For information regarding the accessible shallow well handpump, see New Accessible Handpump for Campgrounds (Kuhn and Beckley 2005) at http://www.fs.fed.us/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm05712311. This Web site requires a username and password. (Username: t-d, Password: t-d)

Figure 7–11—An accessible handpump

for shallow wells.

Water Troughs

Most horses and mules are comfortable using traditional, economical metal or plastic stock tanks— also called troughs. Avoid using low troughs—1-foot (0.3-meter) high or less—that sit on the ground. Curious stock may paw at them and get their hoofs caught or flip the trough. Figure 7–12 shows a trough that is 2 feet (0.6 meter) high and suitable for an area with a low to moderate level of development. The trough features a convenient automatic fill device with a protective screen that prevents curious stock from damaging it. Cold climates require frost-free hydrants. Figure 7–13 shows a trough suitable for a high level of development. Many riders prefer watering their stock in clean, freshly filled water troughs.

Figure 7–12—Stock can paw at a short trough and flip

it. A tall trough, such as this one, is a better choice. A

screened cage protects the automatic fill device from

curious stock or other animals.

Horse Sense

Watering Holes

You can lead a horse to a public water source, but it may not drink. A dehydrated horse may not drink because its judgment is clouded by lack of salt. A healthy horse may refuse water that smells or tastes differently than the water it is used to drinking. Many riders prefer watering their animals in clean, freshly filled water troughs.

Figure 7–13—This attractive water trough is

convenient, but costly.

Horses and mules suck water into their mouths through lips that they keep mostly closed. They can get a hearty drink from a water source that is only a few inches deep. Some innovative shallow troughs fill for a single animal's use. After the animal has finished, the remaining water flushes into the drainage system. The raised shallow basin permits stock to see in all directions while drinking (figure 7–14). These troughs are appropriate only in highly developed sites. Table 7–3 shows the relative characteristics of water troughs and indicates the suitable level of development for each type.

Figure 7–14—A raised water basin allows stock to

see in all directions when drinking. This style is

suitable for areas with a high level of development.

Horses and mules are not the only animals that use water troughs in recreation sites. Small wildlife in search of water may jump up on the edge, or reach into, stock water troughs. If they lose their balance, they can fall in and drown. A wildlife ramp (figure 7–15) supplies an escape route for small, trapped animals. Contact the appropriate wildlife and conservation agency for applicable regulations and design guidelines.

Figure 7–15—Water troughs with an escape ramp are

lifesavers for small, thirsty wildlife that otherwise

might have drowned after falling in.

Water troughs require a surrounding area that is clear of vegetation, signs, and other obstructions. When surroundings are clear, stock can drink from either side and avoid conflicts. The size of the wearing surface will vary according to the size of the water trough. Figure 7–16 illustrates a 4-foot water trough that has an adequate clear area with an aggregate wearing surface. Water troughs also require regular maintenance. To prevent them from getting plugged, drain debris and standing water regularly. Mosquitoe that carry serious stock diseases, such as West Nile virus, breed in standing water. In some areas of the country, water troughs must be scrubbed frequently to remove scum, algae, or mineral deposits.

Figure 7–16—A 4-foot water trough installed

on a wearing surface.